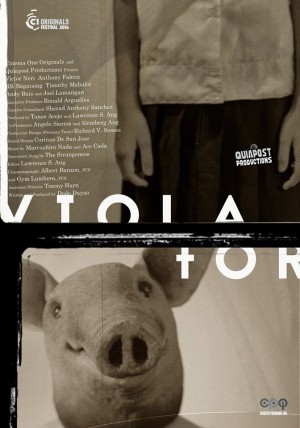

Dodo Dayao’s ‘Violator’: Outplaying the demon within

MANILA, Philippines—At first, first-time director Dodo Dayao’s “Violator,” a 2014 Cinema One Originals entry, could be passed off as a usual crime movie. But as the minutes drag along, it slowly reels itself out into a horrifying picture, ready to gnaw at your inner being in any moment.

In the destructive idleness of time one stormy night, five men suddenly find themselves whirred into the pits of hell upon the arrival of a mysterious boy in the Precinct 13 they get stranded in.

Dayao, who is widely known in the local indie film circuit as one of the finest, more credible film reviewers, obviously knows how to combine surprise and terror but he doesn’t dole them out right away until the bone-jarring climax.

He wants to be calm at the beginning, presenting ambiguous stopgaps that befuddles the mind as much for their unsuspected impression as for their shocking impact.

As if a woman casually jumping off a building into unimaginable depths is not enough, then wait until you see a teacher finding her student bloody and lifeless inside the classroom and two close mates excitedly setting themselves on fire atop a gorgeous hill.

Article continues after this advertisementThen comes the recurring ghost of a cult leader, an old white-haired man who shows himself to the protagonists with a dark message he seems to try to get across.

Article continues after this advertisementThe accumulation of disconnected yet potent scenes converge into one sinister road with a snaky demon in the middle of the way waiting to execute his violation to his prey.

A jigsaw puzzle

Dayao doesn’t give much background to his characters. He, however, put an enigma to their personal lives with scenes that sift their system of morality wherein lines of right and wrong are indistinct if not blurred.

Police officer Lukas Manabat (Anthony Falcon) gets caught up in affair with his girlfriend, whose son watches them making love in the bedroom. Meanwhile, Benito Alano (Joel Lamangan), a widower and the chief of police, resigns himself from believing in a god, a conviction apparent when he shoots one by one saint replicas in his home.

Troubled by his nagging conscience, Gil Pring (Victor Neri) feels a bit of disgrace after his group guns down an evasive criminal. Similarly, Mang Vic (Andy Bais), the precinct janitor, is racked by guilt and keeps on apologizing to his daughter after he commits a transgression against her.

In retrospect, Dayao prods us to turn in any way possible the nature of the characters like pieces on jigsaw puzzle and interlock them with their respective predispositions to complete the whole picture.

“Violator” poses a question on our capability to ward off the devil that obstinately wants to invade our system, or to welcome it in open arms with the choice of letting it control us or the other way around.

It also seems to ask whether we are fundamentally detached to the forces of good and evil, like it is just one of the perturbable manifestations of our worldly disillusionment or whether we humans, in actuality, are by nature evil.

Skipped heartbeats, shaky nerve-endings

“Violator”, like what we’ve mentioned earlier, is Dayao’s first feature film and the genre he gets to choose proves to be a venture worth taking.

The film’s keen cinematography breeds a surrealist aura in a very affecting manner that builds up from its very exposition up to its denouement. The entire picture has the color of ink, analogous to the shadowy theme it proposes.

Unlike in the usual gory thriller movies where handheld shots equate chaos, “Violator “is shot in a steady style, further animated by well-executed scenes and performances by the entire cast.

On top of that, the editing is skillfully done, with moments of slow pace that eventually picks up to deliver the film’s high point—the maddening blackout scene at the precinct, followed by the on-and-off flickering of lights. The sound cues here are complete torture, inducing skipped heartbeats and shaky nerve-endings to its unguarded crowd.

Dayao’s talent on writing is something to be taken seriously. The audience must fully open their ears to catch the parting dialogues between Alano and the boy Nathan (the devil himself), which are riddles to be deciphered and analyzed.

It is refreshing to see a complex and unique brand of horror projected on big screen. It’s Dayao’s first, and hopefully not his last.

RELATED STORIES

‘Red’: Beyond fixing life and love

Esprit de Corps: The naked truth when boys become men—or not