Cynthia Nixon on suppressing one’s sexuality: People who want to kill parts of themselves are never going to succeed

Vincent D’Onofrio (left) and Cynthia Nixon

It was hard to contain our excitement when we interviewed Cynthia Nixon—yes, that’s headstrong lawyer Miranda Hobbes of “Sex and the City”—for her portrayal of lesbian careerwoman Gwendolyn Briggs, the formerly married press secretary of misogynistic Governor George Wilburn (Vincent D’Onofrio).

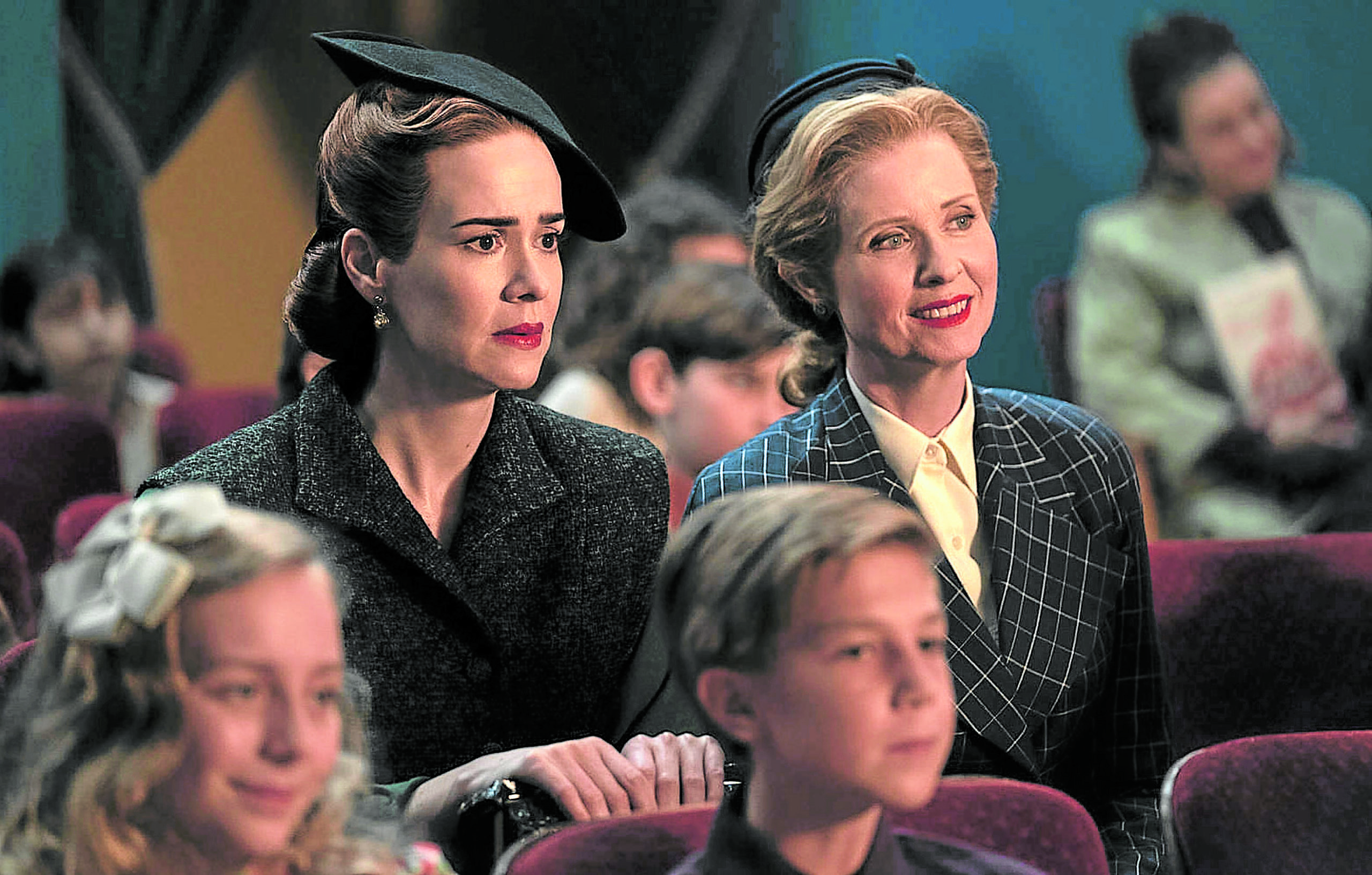

In the Netflix series “Ratched,” Gwendolyn helps title character Nurse Mildred (portrayed by the lovely Sarah Paulson) turn her tiringly wretched life around.

It’s a case of art somewhat imitating life for Cynthia: The 54-year-old Emmy (for “Sex and the City,” “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit”), Grammy (best spoken word album for “An Inconvenient Truth”) and Tony-winning (“Rabbit Hole,” “The Little Foxes”) actress and activist has two kids with Danny Mozes, with whom she was in a relationship till 2003. Thereafter, Cynthia began dating education activist Christine Marinoni in 2004, then married her eight years later in New York.

As Cynthia told The Daily Telegraph in 2007, the “sexual orientation switch” wasn’t really born out of secrecy. “I don’t really feel I’ve changed,” Cynthia shared. “I had been with men all my life, and I’d never fallen in love with a woman. But when I did, it didn’t seem so strange. I’m just a woman in love with another woman.”

In Netflix’s visually sumptuous origin story of the iconic head nurse from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” Gwendolyn decisively comes out of the closet to declare her love for the closeted Mildred.

Article continues after this advertisementThe eight-part series boasts a star-studded ensemble delivering finely tuned performances, but the gloriously understated Cynthia and the scenery-chewing Judy Davis, who plays Mildred’s archenemy Nurse Betsy Bucket, quickly set themselves apart from the rest of Ryan Murphy’s stable of fine thespians.

Article continues after this advertisement

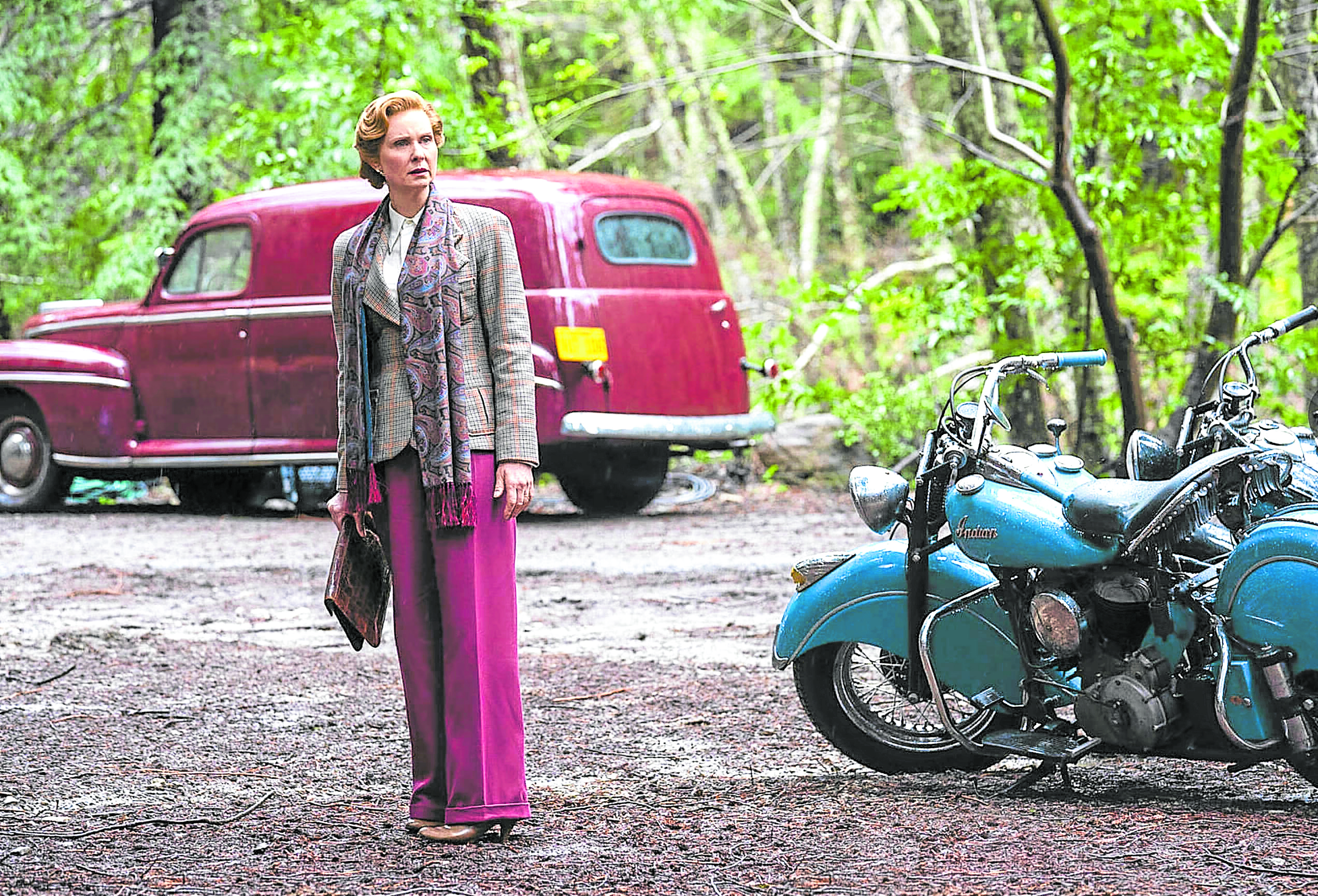

Nixon

“The show tackles serious themes on mental illness—how we view it, and who gets to decide who is mentally ill and who isn’t,” Cynthia told us in this one-on-one Inquirer Exclusive video chat. “It’s safe to say that almost all of the characters in the show seem to suffer, to some degree, from mental illness—except for Gwendolyn.

“She is the only truly sane character, and she is the only one who really faces all the different truths about herself. She accepts them and owns them. And, for me, Gwendolyn provided me with a very different part. I usually portray people who are a little more warped (laughs). So, it was both a challenge and a treat to play someone who is so purely devoted [to the object of her affection] … who is purely a force for good and who’s very much at ease with herself.”

More than that, Cynthia believes in what Ryan Murphy is trying to accomplish in his star-studded productions: He’s turning the spotlight on the underrepresented sectors of society.

“What Ryan Murphy does is very important,” Cynthia mused. “One of the things that I learned in this series is how big of a student Ryan is of the cinema of the ’40s and ’50s. He loves them, and it shows.

“But, as a gay person, Ryan is also ‘very much aware’ of [the existence of] all types of people—people of color and queer people who were almost entirely absent in those films! So, with his productions, he ‘goes back’ and puts us back in!

“That’s one of the things that I love so much about being able to play Gwendolyn. There were so many gay women like her in that time period that we never got to see because they’ve essentially been erased!”

Nixon (right) with Sarah Paulson in “Ratched”

Excerpts from our chat with Cynthia:

Long before Gwendolyn, there was Miranda Hobbes, who was just as iconic as her peers and BFFs in “Sex and the City.” What have you learned from her?

I feel like, in a smaller way, Miranda was the type of person that was never revealed to viewers before [the show came out] … a woman who was primarily a professional, who was totally career-oriented, very driven about her career, and for whom love, marriage and motherhood were not even in her mind. They were just something she had a vague awareness of and had no real interest in.

And I think it was wonderful for viewers to get to see a careerwoman like that … and to get to love her. We sometimes think of overworked women like Miranda as “not very fun.” I mean, maybe Miranda wasn’t as fun as Samantha Jones (played by Kim Cattrall), but she was fun for her.

I think we, and all of the characters in “Sex and the City,” learned that single women in their 30s and beyond were capable of having a good time. They were not necessarily solely focused on getting married.

While Gwendolyn had to initially struggle with her sexuality, you made it very clear in your performance that this is a woman who knew what she wanted. Are you anything like her?

She’s very clear about what she wants, yes … after some initial ambiguity. I guess I am similarly a very, very clear person. Also, the thing that I love about her, which may be different from me, is the fact that she really is very taken with Mildred, with whom she almost immediately falls in love.

She has a mission to rescue her. She sees that Mildred has such potential for happiness … but she also knows she’s suffering so deeply. Gwendolyn really thinks she could “save” her and make a real difference in this person’s life.

Cynthia Nixon

In terms of the show in general, didn’t you find it daunting that you guys were creating a sort of prequel to something as iconic as “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest?”

It is intimidating to do a series about a show that is so iconic. I mean, it was probably very intimidating for Sarah Paulson to play the character of Nurse Ratched, as it would have been for me had I been doing it.

But, no, I mean it’s a terrific production. It’s a movie that aged very well, and all the performances have also aged very well. But it’s not too hard to realize that “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” is also a deeply misogynistic film.

So, I think it’s a brilliant idea to sort of “rescue” the Ratched character and take a look at it through a feminist lens and say, “OK, we think of this character as a monster.” First of all, is she really a monster? And second of all, if she were a monster, how did she become one? What happened to her? What could turn someone into a person who’s cruel and emotionally shut off from the cruelty that she is inflicting on others?

Does Gwendolyn think her love can transform the monster in Mildred, because as we see in the show, she eventually realizes what Mildred is up to?

It’s an overarching theme of the production … that people who hate parts of themselves, as well as those who want to kill parts of themselves, are never going to succeed. That if you have some deep, dark part of you that you want to push down, you’re not going to succeed.

Eventually, that part of you is going to come back—bigger and stronger than ever! And so that is one of the great truths that Gwendolyn wants to impart in Mildred. Maybe before we met her, Gwendolyn also struggled with her sexuality and had to hurdle self-hatred because of it.

But she has gotten past it, and I think that’s one of the big themes here: If there is some part of you that you don’t like, the only way to deal with it is to accept it and embrace it. Then, look at it in the light of day and reevaluate. See what can be done. Don’t try to shut it down.

What were your biggest challenges in terms of characterization?

The thing that I struggled with, and which I found difficult, was how simple Gwendolyn was as a person. Too often, I get to essay characters that are more ornate, or roles that are very detailed, like fine embroidery.

In this case, I just had to be wholly and purely good, loving, optimistic and determined. And believing that my characterization was going to be interesting enough for the audience to watch, even without all the little embellishments, I think that was the hardest.