3rd edition of Tingin Asean fest shines spotlight on indigenous peoples, migration

“The River Flows”

If last year’s Tingin Asean Film Festival painted a composite picture of modern Southeast Asia, its third edition intends to look deeper into the region’s history.

The cinematic showcase, organized by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), begins its four-day run at Shangri-La’s Red Carpet Cinema today.

Indeed, Midi Z’s “The Road to Mandalay,” Dain Zaid’s “Dukun,” Kulikar Sotho’s “The Last Reel,” Joko Anwar’s “A Copy of My Mind,” Maw Naing Aung and The Maw Naing’s “The Monk” and Laos’ five-part anthology “Vientiane in Love” brought global themes and issues closer to home last year.

This year, the NCCA wants viewers to develop deeper appreciation for the different cultures in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) by way of Tingin’s 2019 lineup. (Visit @TinginASEANFilmFest on Facebook, or e-mail tinginaseanfilmfest@gmail.com.)

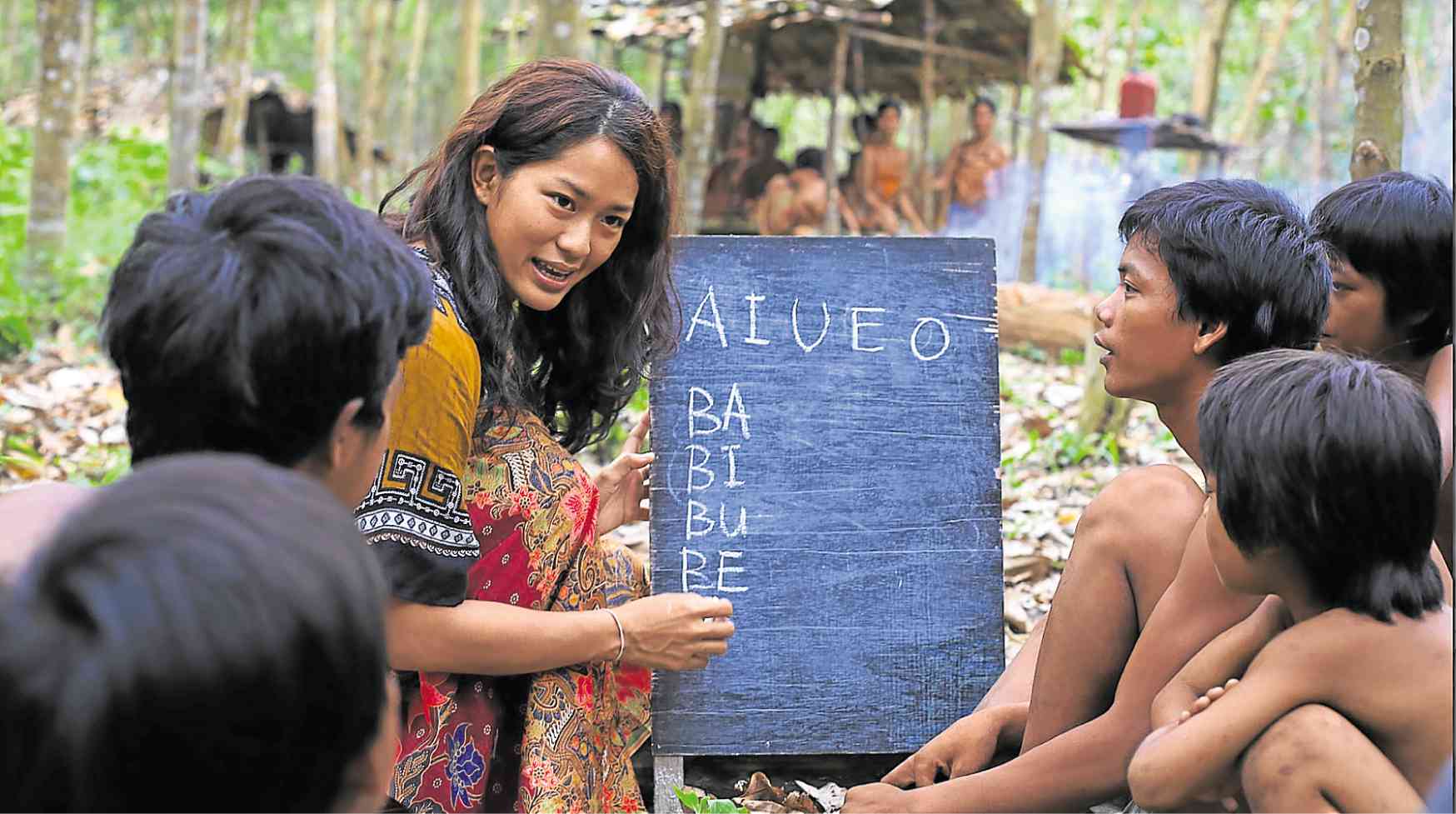

Aside from Rithy Panh’s “Graves Without a Name” (Cambodia), which opens the festival tonight, the list includes Edmund Yeo’s “Aqerat” (Malaysia), Abdul Zainidi’s “Anggur in Pockland” (Brunei), Nontawat Numbenchapol’s “By the River” (Thailand), Tin Win Naing’s “In Exile” (Myanmar), Sanif Olek’s “Sayang Disayang” (Singapore), Riri Riza’s “Sokola Rimba” (Indonesia), Thi Trinh Nguyen’s “Love Man, Love Woman” (Vietnam), Makoto Kumazawa’s “The River Flows” (Laos), Bagane Fiola’s “Baboy Halas” and Brillante Ma Mendoza’s Nora Aunor starrer “Thy Womb” (Philippines).

If you notice more documentaries in its current entries, that isn’t an accident, says festival programmer Patrick Campos. “There was a conscious decision to program a lot of docu films to reflect the shape and tendencies of regional cinema,” he explains to Inquirer Entertainment.

“Making documentaries is very important in the region. The form allows filmmakers to be independent in the use of resources, the process of filmmaking, and the choice of topics. Moreover, it is a direct way of commenting on societal issues.”

More than the choice of genres, the festival wants Filipino moviegoers to understand their neighbors in the Asean before reaching out to countries that are otherwise far from or out of their reach.

Annie Luis, head of the NCCA’s International Affairs section, explains this further.

“Tingin is the longest-running film festival dedicated to Southeast Asian cinemas,” she points out. “The Philippines has been a part of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for more than 50 years, yet we know so little about our neighbors’ cultures.

“Tingin encourages Filipinos to gain a deeper understanding of and therefore form closer ties with our Asean peers. This year, it takes up the cudgels for indigenous peoples, who continue to be marginalized in society.

“Most of these films shine a light on their struggles as much as their fascinating cultures. They also celebrate indigenous peoples’ languages, which are in danger of becoming extinct. Language, which is a carrier of culture, must be safeguarded.”

Is this the reason why Tingin has chosen Bagane Fiola’s “Baboy Halas”—a 2016 QCinema winner which dramatizes the fascinating story of an indigenous family coping with the harsh and discombobulating changes in the continually evolving world around them—to represent the country in the festival?

“There are, in fact, many possible films from the Philippines, and we did consider a number of them,” states Campos. “But in keeping with both the focus of this year’s festival—i.e., indigenous peoples and the notion of place-making and displacement—and how a film could converse and be compared with other films in Tingin, we selected ‘Baboy Halas.’

“Fiola’s work presents a method for gathering the stories of indigenous groups, and his way of grappling with how to tell them in an inventive but ethical way.

“Sokola Rimba”

“We can compare this film with other selections in the festival, like ‘Sokola Rimba’ and ‘By the River,’ among others, that seek to do the same, but using other filmic strategies and from other angles.”

While there are still cross-cultural collaborations this year, like the Lao-Japanese coproduction “The River Flows,” Tingin is stretching its wings even more by featuring films that breach cultural boundaries.

“This year, there are a number of entries that are not exactly coproductions, but rather films or directors who cross cultural boundaries,” Campos notes. “For instance, filmmakers based in France return to Cambodia (‘Graves Without a Name’) and Brunei (‘Anggur in Pockland’) to make movies about home.

“Aqerat”

“A Burmese filmmaker follows the lives of Burmese exiles in Thailand (‘In Exile’). And the Malaysian selection (‘Aqerat’) is set in the Thai-Malaysian border and features the issue of Rohingyan statelessness.

“These films were selected to give a vivid picture of how borders are porous, and how places are made and unmade in contemporary Southeast Asia.”

Aside from screening acclaimed films from the Asean region, the fest aims to consolidate its gains in the past three editions of Tingin, says festival director Maya Quirino.

“Tingin continues to strengthen its master class program, which is unique to the festival,” she says. “We always allocate a portion of the budget to inviting master filmmakers from Southeast Asia, like Yeo, Numbenchapol and Fiola this year, to share their skills and experiences with the next generation of Filipino filmmakers.

“We also have lectures for moviegoers to enrich their film grammar, knowledge of film history, and so on.”

Nora Aunor in “Thy Womb”

Other than “Thy Womb” and “Baboy Halas,” here are the synopses of some of the films we’ve seen, so far:

“Aqerat” (We the Dead), which won the best director prize at the Tokyo film fest, tells the story of Hui Ling (Daphne Low), a woman who juggles odd jobs at the Thai-Malaysian border to survive.

Determined to make it even when she loses all her savings to a thief, she accepts her boss’ offer to earn a quick buck—as a human trafficker!

In “By the River,” the Karen indigenous people of the Southern Klity village of Kanchanaburi in Thailand fall victim to lead poisoning and other health crises when a mining and mineral-processing company dumps its waste in the areas surrounding it.

Cannes-winning director Rithy Panh’s “Graves Without a Name” explores grief and loss under the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Panh had lost many members of his family under the violent regime, and in this film, he searches a path to peace.

“Love Man, Love Woman”

“Love Man, Love Woman” is about Master Luu Ngoc Duc, one of the most prominent spirit mediums in Hanoi, and his vibrant community.

It explores how gay men in Vietnam have established connections and found a venue for expression under the tenets of the popular religion, Dao Mau.