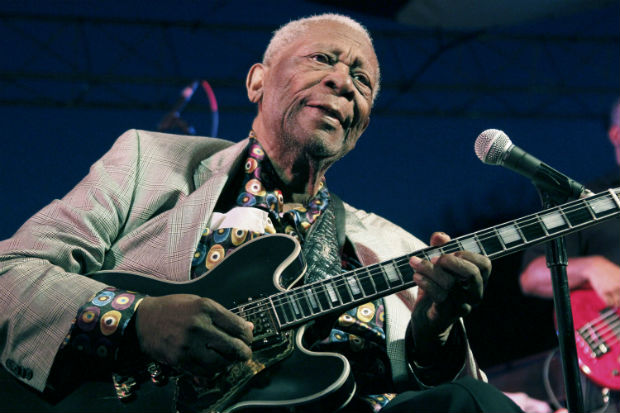

With BB King’s death, a blues era draws to end

NEW YORK, United States — The crowd in 1968 San Francisco was unlike any BB King had seen before. The Mississippi-born bluesman, established on the African American circuit, faced a white audience of long-haired hippies.

King, who died Thursday at 89, later called the concert the greatest of the thousands he played over his life. And it marked the start of a cultural exchange whose era, with his death, is drawing to a close.

“For the first time in my career I got a standing ovation before I played. Couldn’t help but cry,” King later recalled in his memoir of the show at San Francisco’s Fillmore West.

“With tears streaming down, I thought, ‘These kids love me before I’ve hit a note. How can I repay them for this love?'”

The concert, arranged by promoter Bill Graham to the rising countercultural scene, set King’s career on a new trajectory.

He opened the following year on a legendary US tour of the Rolling Stones and soon appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” finding a surprise new audience in white Middle America.

The newfound platform gave King a role he relished as ambassador of the blues, a genre that had come of age after emancipation from slavery with roots in African-American spirituals and a narrative style at once melancholy and serene.

Memories of South

King was one of the last bluesmen who grew up in the segregated, pre-World War II American South. His music frequently evoked the deprivations of the era, when he toiled in cotton fields as a child.

“On the plantation we used to say that we worked from ‘can to can’t’ — from when you can see, until you can’t see,” he recalled in a 2007 interview with AFP.

Despite winning wealth and honors ranging from 15 Grammys to the Presidential Medal of Freedom, King in his nearly nightly concerts kept alive classic blues songs such as “Every Day I Have the Blues” and “Sweet Little Angel.”

“The blues has lost its premier ambassador, someone who was very conscious that he was trying to bring more dignity to a musical form that had been traditionally subject to ridicule or looked down upon,” said Scott Barretta, a music scholar and former editor of Living Blues magazine.

Keeping the blues alive

King often said that he kept playing because he feared the blues would disappear without him.

In the end, King not only preserved the blues but, through his crossover appeal, helped shape rock.

Generations of guitarists grew up on King’s distinctive style, with an emphasis on crisp, elegant single notes and vibrato, rather than chords or the slides used by most Mississippi Delta bluesmen.

Some of his most visible influence came when his records — and later King himself — traveled across the Atlantic.

Besides the Rolling Stones, fellow British band Cream and its now superstar guitarist Eric Clapton were profoundly influenced by King.

Other artists indebted to King, even if the influence was not as immediately apparent on first listen, included Jimmy Page of hard rock pioneers Led Zeppelin as well as Fleetwood Mac and Carlos Santana — who saw King at the Fillmore West.

‘Being black twice’

While remembered posthumously for his broad musical appeal and warm demeanor, King at the start of his career was considered an unlikely candidate to appeal to white audiences.

He famously said that playing the blues was “like being black twice” — he expected to be written off as only relevant to African Americans.

Unlike rocker Chuck Berry, or even late fellow blues artists John Lee Hooker and Ray Charles, King had little interest in energetic crowd-pleasers and stood by his steady-paced, upright blues.

Before he played the Fillmore West, King was also falling out of favor with African-American audiences who saw him as old-fashioned. King long remembered being booed by teenagers in the 1960s at Baltimore’s Regal Theater, then a top African-American music venue.

But King insisted that his interest was not in crossing over, but in bringing fans to the blues.

One of the last surviving blues elders, Buddy Guy, a 78-year-old giant of the Chicago scene, called King “my best friend and father to us all.”

“The way B.B. did it is the way we all do it now” Guy wrote on Facebook.

“I love you and I promise I will keep these damn blues alive. Rest well.”