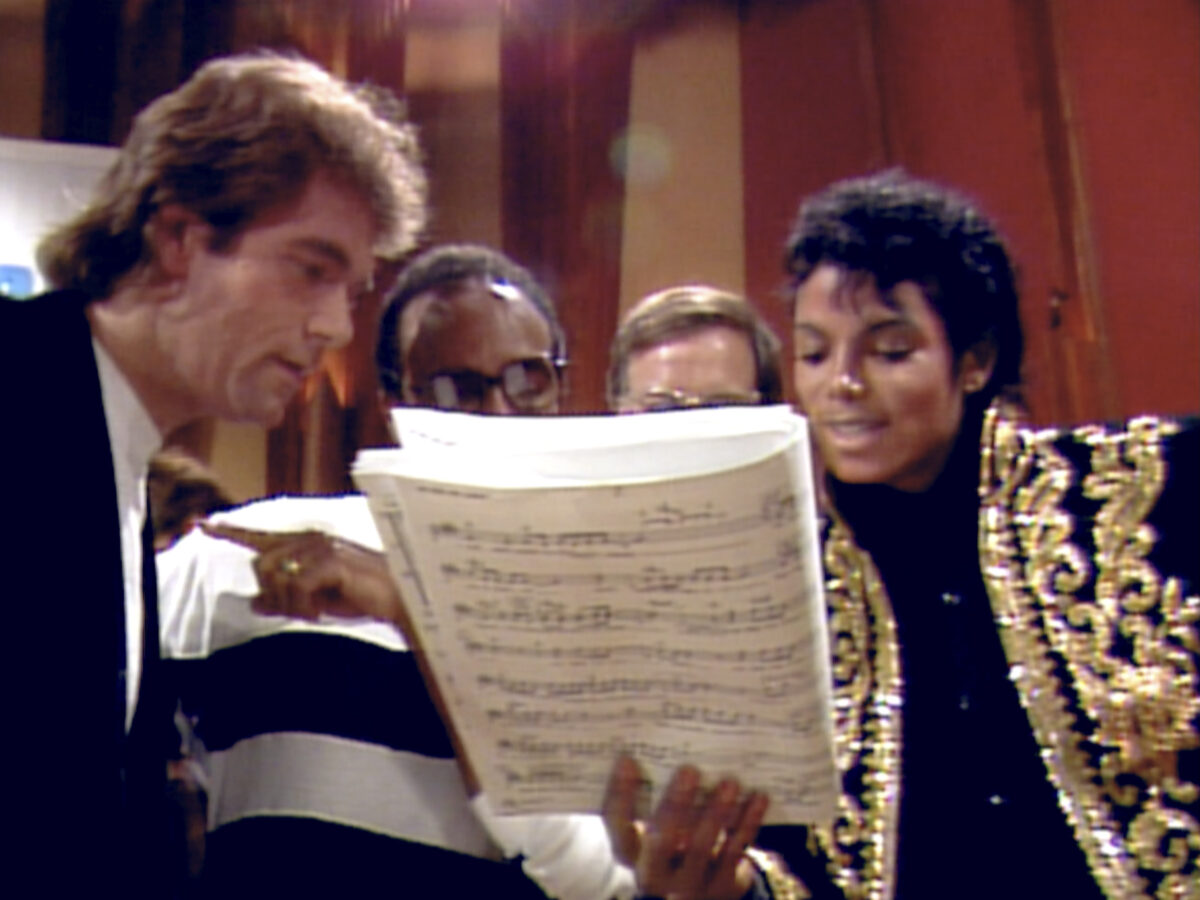

This image released by Netflix shows, from left, Huey Lewis, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson, right, in a scene from “The Greatest Night in Pop.” (Netflix via AP)

NEW YORK—Thirty-nine years ago, the biggest music stars in the world crammed into a recording studio in Los Angeles for an all-night session that they hoped might alter music history.

“We Are the World” was a 1985 charity single for African famine relief that included the voices of Michael Jackson, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Ray Charles, Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, Paul Simon, Tina Turner, Dionne Warwick, Lionel Richie, Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen.

Fans get a chance to almost step into that recording session this month with the Netflix documentary “The Greatest Night in Pop,” a behind-the-scenes look at the complex birth of a megahit. It starts streaming Monday, Jan. 29.

“It’s a celebration of the power of creativity and the power of collective humanity,” says producer Julia Nottingham. “The amazing thing about the song is it’s such an inspiration for so many artists.”

The filmmakers got fresh insights after landing interviews with Richie, Springsteen, Robinson, Cyndi Lauper, Kenny Loggins, Dionne Warwick and Huey Lewis—and for an added bonus spoke to them inside A&M Studios, the site of their triumph in 1985.

“I knew it was important to re-create those memories by just sort of walking into that room and what that energy created for them,” said director Bao Nguyen, who was only 2 when the single came out.

READ: ‘We Are The World,’ Yolanda version

The filmmakers married never-before-seen footage taken from four cameras that captured the USA for Africa session with audio from journalist David Breskin, offering insight into the dynamics and drama in the room that the official music video could not.

“The Greatest Night in Pop” isn’t shy about exploring some of the more unflattering things, like Al Jarreau having a bit too much wine and how Dylan was out of his element, needing Wonder to mimic how the Nobel laureate might approach his solo.

Lauper accidentally prolonged the recording session because her jangling jewelry fouled up the recording, while Prince, who was at a Mexican restaurant on the Sunset Strip, offered to do an isolated guitar solo. Sheila E confesses she felt like she was invited to the recording session just to lure Prince in. In the end, Prince never made it, robbing the single of a Jackson-Prince double punch.

“For me, it was just important that we told a story that was honest,” said Nguyen. “It is an honest story about the night and all the things that could have gone wrong—that did go wrong—but at the end of the day, it became this beautiful family.”

The details in the doc are glorious: The image of Joel kissing then-wife Christie Brinkley before heading into the studio, and the nugget that Springsteen drove himself to the location in a Pontiac GTO. Other highlights: Watching singer-songwriter Joel explore an alternative lyric, the stars gathering around Wonder on a piano for the first run-through, and Richie, ever the ambassador, smoothing over potential disputes.

There’s a moment when the 40-plus superstars are asked to groove from their knees and stop pounding their feet on the risers, which was throwing off the sound. Producer Quincy Jones tried to head off any hubris by taping up a sign: “Check Your Ego at the Door.”

READ: The prescience, timeliness of one of MJ’s beloved songs

In an interview with the AP at the Sundance Film Festival, Richie recalled that having Charles there was helpful, since he was revered. The presence of Dylan also helped neutralize any griping.

“We got the right players to come in. And then once we realized we were trying to save people’s lives, then it’s not about us anymore,” Richie said. “But to deliver that in one night? An impossibility.”

The documentary anchors the effort in the activism of Harry Belafonte, who had raised the alarm about famine in Ethiopia, and having him in the studio singing “We Are the World” was poignant.

The group—exhausted and giddy in the wee hours—also serenaded the legend with a spontaneous version of Belafonte’s “Banana Boat,” with the lyrics “Daylight come and we want to go home.”

It is revealed that Loggins suggested that Huey Lewis replace Prince in the solos, right after Jackson. No pressure, right? “It was just one line, but my legs were literally shaking,” Lewis recalls in the movie.

There was a key moment when Wonder suggested that some lyrics be sung in Swahili, an idea that prompted Waylon Jennings to balk. The idea was scrapped when it was learned that Swahili wasn’t spoken in Ethiopia. There’s also footage of Bob Geldof, who was a driving force behind Live Aid, inspiring the group in a speech before the session. The Live Aid concert would happen that summer.

The documentary also goes back to explore the events before the recording, like that song co-writers Jackson and Richie were still working on it 10 days before the recording session on Jan. 28, 1985. Once in the studio, footage captures superstars—no assistants allowed—nervously hugging. “It was like first day at Kindergarten,” Richie says.

The decision to pick that particular night to record the single was made in order to piggy-back off the influx of music royalty attending the American Music Awards, hosted by Richie, who performed twice and won six awards. The cream of the cream then made their way to the all-night recording session at A&M Studios.

Lauper, who dazzled everyone with her vocal prowess, was almost a no-show. Her boyfriend counseled her to skip the recording because he thought the single wouldn’t be a hit. But Richie told her: “It’s pretty important for you to make the right decision. Don’t miss the session tonight.”

Nottingham, the documentary producer, isn’t sure such a similar recording session with music superstars could ever happen these days, especially with ever-present social media and armies of assistants.

“It was very ahead of its time in terms of it being the ’80s and technology. But I would hope it would serve as an inspiration for other artists to keep trying and do these things for great causes.”—With Ryan Pearson