How ‘Dekada ’70’ invites young people to embrace their strengths, and care

A poster of the musical “Dekada ’70”. Image: Facebook/@dkd70

The director and playwright of “Dekada ’70”, Pat Valera, envisioned that his adaptation of Lualhati Bautista’s Palanca award-winning book would be watched and understood by young people.

Valera and some of the original cast members, Stella Cañete-Mendoza (Amanda Bartolome), Jon Abella (Jules Bartolome) and Abe Autea’s (Bingo Bartolome), spoke with INQUIRER.net last Saturday, Feb. 22, and voiced out their insights about the play, some of which touch on its relevance to the young.

The production invites its audience from all walks of life, regardless of age, gender, social status and even political alignment, to take a seat at the Doreen Black Box Theater in Arete, to awaken their political consciousness, especially if it has already gone into a deep slumber.

The play, now on its third run, was initially staged in 2018 as Valera’s thesis production requirement at the University of the Philippines Diliman, where he graduated in 2019.

Valera revealed that he first decided to adapt Bautista’s play after the news about former President Ferdinand Marcos’ burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani rocked the nation and gave rise to protests.

“The art and the theater should respond to this,” Valera said, referring to the burial of Marcos in a cemetery supposedly for heroes. Since then, the play’s concerns have “compounded” to tackle more issues such as the suppression of press freedom and “the need for memory to continue.”

True to the source

Bautista’s novel was told through the perspective of Amanda Bartolome, a housewife and a mother of five boys, as their family lived through the 1970s, before and during the time when Marcos declared Martial Law.

While Amanda’s five boys, Jules (Julian Jr.), Gani (Isagani), Em (Emmanuel), Jason and Bingo (Benjamin) grew up and started forming their own beliefs in their journey towards becoming “men of life,” Amanda also started her own journey towards liberation. From a life supposedly centered around “a man’s world,” step-by-step Amanda freed her mind from the confines of her middle-class lifestyle.

The musical transforms Bautista’s depiction of the decade to a play which also highlights the plight of the masses surrounding the Bartolome family. The musical’s ensemble echoes the political unrest of the period through its songs and its portrayal of political prisoners during the 1970s, which Valera assured was backed by extensive research.

Image: Facebook/@dkd70

‘Dekada ’70’ as a musical

The play’s third run began in Feb. 21 and is extended until March 14. The bare rectangular theater which houses “Dekada ’70” booms with life and music as the characters perform their well-choreographed song-and-dance numbers, and deliver their heart-wrenching dialogue. Even the comedic banter between the Bartolome boys drives the audience into waves of laughter and intense emotion.

“Dekada ’70” transitions from one scene to another, often with compelling ballads or upbeat protest hymns, written by Valera and the play’s musical director Matthew Chang.

When Valera was asked why the novel was transformed into a musical, he explained that the initial plan was to make a play with music. Valera later on realized the undeniable power of musicals, which led the team to want “to bring out the emotion” in the story.

Valera cited that one of their inspirations for turning the play into a musical was a fellow artist, film director Pepe Diokno, who said, “One day we will sing our own songs.”

Diokno’s words became the play’s framework when they were writing the script, which compelled them to “sing their own songs as well.”

One of the play’s most powerful songs, “Bayan, Bayan, Bayan Ko” was performed by the play’s ensemble. The upbeat song, filled with heavy bass lines, electric guitar riffs, rapid beats and multi-layered vocals, invites people to take a stand and continue fighting.

“Tao, bayan/ Kailan maninindigan?” the ensemble repeatedly sings.

Despite acknowledging the songs as “larger than life,” Valera clarified they had to tread this line carefully to avoid making a “spectacle out of history.”

“We must find our own truth on how we sing it, hangang saan ‘yung (what are the limits of the) spectacle, per se,” Valera stated. “To be objective about it as well.”

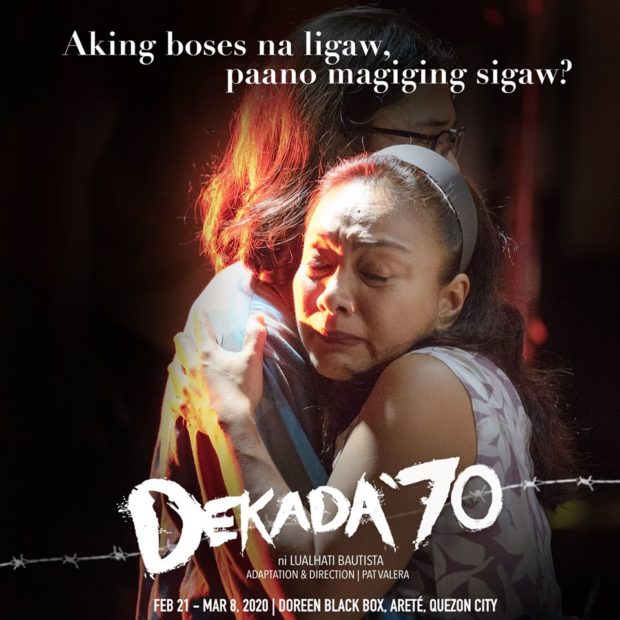

Image: Facebook/@dkd70

Art as a form of resistance

In the play, two of the most radical characters were Jules and Em Bartolome. Jules chose the militant path by joining the rebel forces, where the “resistance was strong,” and to fully immerse himself to his cause.

Valera consulted Bautista about tapping the potential of the younger Bartolome brother, Em. The writer chose to express his sentiments through the use of his art, by writing satirical skits and plays that reflect the violence and injustice happening in the narrative. When it came to politics, the director therefore said that there are two ways of expressing one’s resistance.

“Ang pakikibaka namin (Our fight), are really through our craft and through our art,” he said, explaining the path of resistance for the artist.

At the same time, the director acknowledged the artists’s “counterparts” who rally on the streets and march up to the mountains. To reiterate his point, Valera emphasized that the play was a product of “daloy ng tinta, giting ng haraya (the flow of the ink and the courage of imagination).”

Who must watch the play?

According to Valera, the play aims to reach the “young who are undecided, who are impressionable.” The youth who “are asking if Marcos was a hero” but answers with “‘I don’t think he’s a hero but…’”

“We only have 200 seats per show and kung baga sana ‘yung uupo doon ay ‘yung mga bata na… nacurious na mas malaman pa o may nagagalit at may namumuong galit from them,” Valera added.

(We only have 200 seats per show and we want those seats to be filled by the younger generation who are curious to know or has rage brewing inside them.)

Much to Valera’s amazement, most of the people who came in and out of the theater are people whom they do not know.

“They’re coming. They’re here, and they are shaken and they start to ask questions,” he added.

Despite the play’s strong political statement, Valera said that they never claimed to provide the answers to the audience’s questions. This highly emotional play, which often became graphic about the violence that its characters were going through, is actually not just a theatric device, according to Valera.

“Di lang kami nagpapaiyak (We are not just making people cry) — that is purposeful,” Valera explained. “Kase nga umaabot na tayo sa point of view na: ‘Pagod na ako.’ ‘Ayoko ng makielam.’ ‘I am hardened now.’”

(We have now reached a point where people say, “I give up, I don’t want to meddle anymore, I am hardened now.”)

This should also explain why the musical relies heavy on the strength of the emotions it elicits, to break the barriers of indifference.

“Even before you get to talk to other people — they must start questioning themselves,” he said. Thus and indeed, learnings are not forced and come naturally, “through high emotion.”

The director said they are hopeful about the play’s impact, exactly because they can see that they have tapped their target audience.

“These are the audience that are coming,” he explained. “These are the audience so maligned by social media, so maligned even by their own peers — as snowflakes, as [supposed] millennials without actions.”

“But what we’re seeing is that this is not true. They are seeking out truth. They are seeking out experiences. Informing their own minds, as well.”

The director also explained why the audience could not help but weep when Jason died after getting beaten up by the police for supposedly carrying marijuana.

“Kase sila ‘yon eh (because it’s them),” Valera explained.

Image: Facebook/@dkd70

What about those who resist this resistance?

When the cast was asked if they would recommend the play to Marcos supporters and officials of the current administration, their answer was a resounding “yes.”

“Why not? You have to listen to both sides,” the actress playing Amanda Bartolome, Cañete-Mendoza, said.

Valera clarified that everyone is welcome to watch the play then addressed the preconceived notion that some audience members might be unwelcome.

“They can come here. It is their right,” Valera declared. “Kami mismo hindi kami magva-violate ng law if we want to uphold the law (We can’t violate the law because we want to uphold the law).”

“But it doesn’t mean that they will be welcomed in a sense na, walang animosity or tension, na habang manonood, if a Marcos comes here and watched the play — of course, that’s being naive.”

(But it doesn’t mean that they will be welcomed in a sense that there won’t be any animosity or tension, if a Marcos comes here and watches the play — of course that’s being naive.)

Valera added that mothers and fathers who are “Marcos loyalists” could come and watch. The director also said that when preparing for the play, he provided the cast with “pro-Marcos materials” and let them be the judge of what they want to believe in.

“If you’re not changed by this at least you have a better knowledge of history or truth… [or] an appreciation na tao rin kame (an appreciation that we are also human),” he said.

“And that’s democracy,” Cañete-Mendoza added. “You present everything and you let the person choose.”

The actress asserted that as citizens of a democratic country, it is the people’s responsibility to “know and listen to as much as we can.” When asked about the aspects of the musical which they think speaks to those who think they are powerless, Cañete-Mendoza pointed out that the play “definitely speaks to women.”

Valera added that the play also resonated with the LGBTQ+ community by having some characters who are “decidedly gay.”

Autea, who played the youngest Bartolome, noted that the play resonated with him as a budding theater actor. Bingo’s eye-opening transition from a young naive boy to a legal adult drove Autea to ask the question, “What is my power now? Where is my power?”

From an award-winning novel that liberated women from the confines of domestic concerns in the 1980s, the musical adaptation of “Dekada ’70″ now pushes for the liberation of the youth from apathy, from misinformation, and from the illusion that their youthfulness is a hindrance rather than a strength. JB

RELATED STORIES:

‘Dekada ’70’ musical Twitter account remains suspended amid show’s opening weekend

‘Dekada ’70’ musical Twitter account now activated after suspension