Kit Harington treads familiar territory in uneven ‘True West’ revival

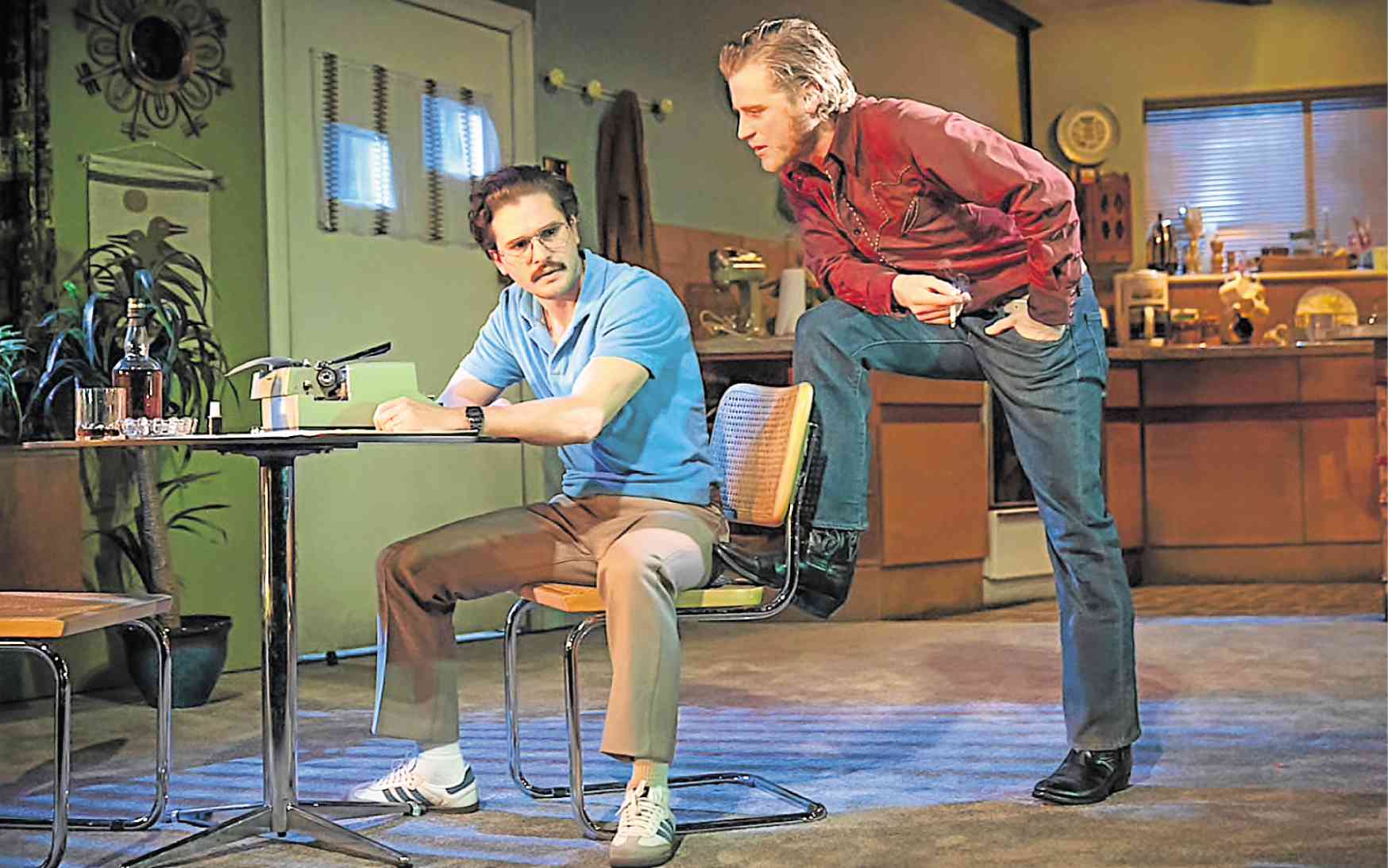

Harington (left) and Johnny Flynn —Photos By Marc Brenner

LONDON—As “Game of Thrones” fans know only too well, portraying a talented guy overshadowed by his domineering and often more assertive siblings is familiar territory for Kit Harington.

Last week, we rushed to see how Jon Snow’s red-hot alter ego cleverly played that off against his aggressive costar, Johnny Flynn, before director Matthew Dunster’s blistering West End revival of actor-playwright Sam Shepard’s “True West” wrapped up its three-month run at the Vaudeville Theatre—and we were glad we did.

These days, it seems inescapable to discuss pop culture without talking about the eagerly anticipated final season of HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” which begins its six-episode run on April 15.

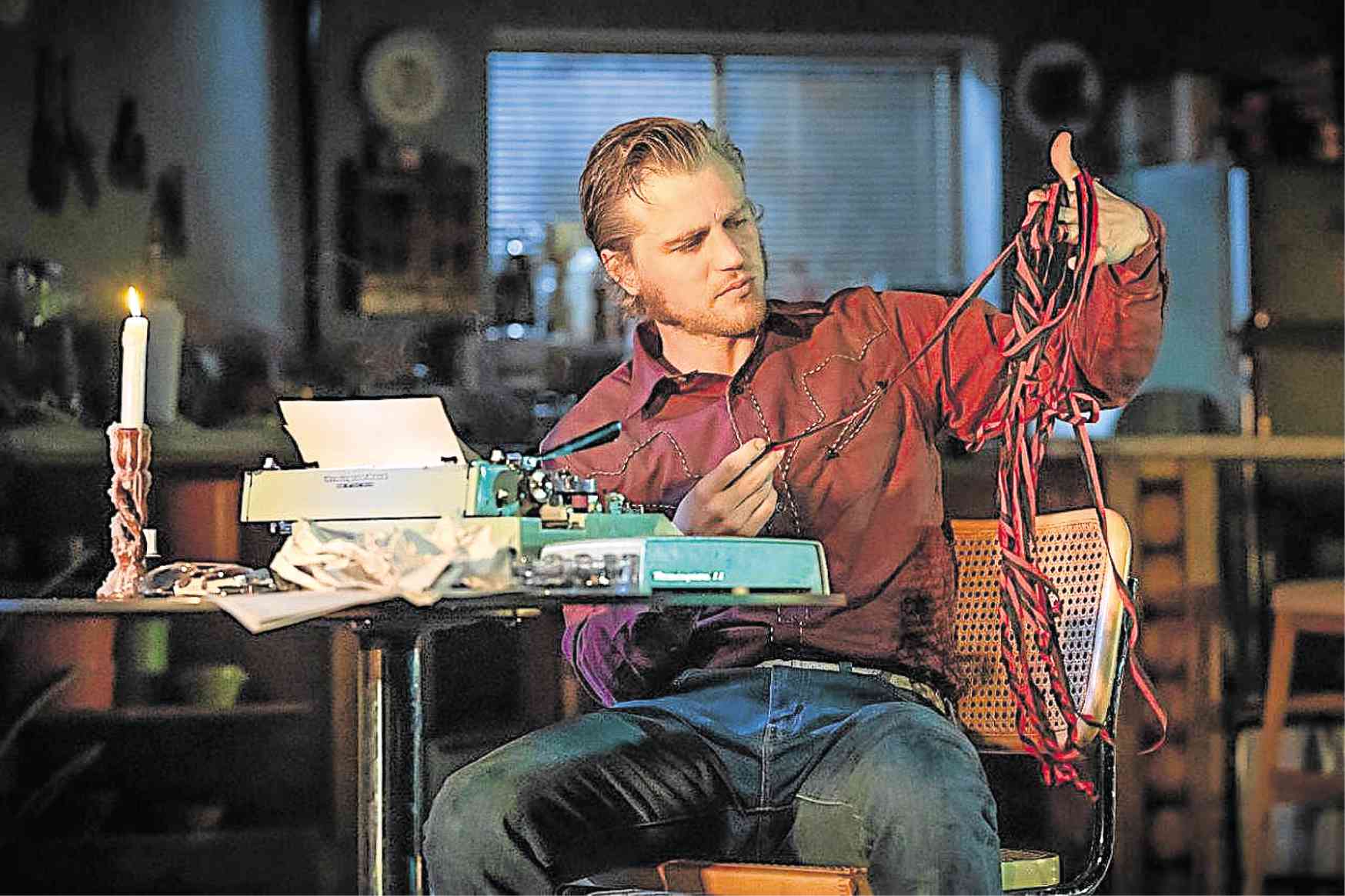

Johnny is the younger half-brother of Jerome Flynn, who plays fan-favorite Bronn in “GoT.” Netflix followers know him as Dylan in “Lovesick,” while NatGeo viewers remember the hard-driving actor as the young Albert Einstein in “Genius.” Up next for Johnny is the lead role in the David Bowie biopic, “Stardust.”

Just a couple of blocks away from Vaudeville Theatre, in a cozy corner of the tourist-heavy Leicester Square, is the Harold Pinter Theatre, which was showing “Pinter 7,” a double-bill that was also on its last week, featuring the Nobel Prize-winning dramatist’s “A Slight Ache” and “The Dumb Waiter.” Among its lead stars was Gemma Whelan, who plays Yara Greyjoy in “GoT.”

Flynn plays the drifter Lee.

We couldn’t wait to watch “True West,” not only because we wanted to see Kit Harington aka Jon Snow in the flesh, but also because the acclaimed play is a must-see for dyed-in-the-wool theater practitioners and enthusiasts.

It is widely considered the last installment of Shepard’s so-called Family Trilogy, the other two being “Curse of the Starving Class” and the Pulitzer-winning “Buried Child.”

(In 2013, we saw Emilia Clarke aka Daenerys Targaryen awkwardly slipping into Holly Golightly’s skin—and into Audrey Hepburn’s big shoes—in the Broadway revival of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” The actress worked hard, sang while playing the guitar, and even showed some skin in a bathtub scene, but her effort didn’t go, uh, lightly, to say the least.)

Aside from his forays into acting (he was Oscar-nominated for “The Right Stuff”), Shepard is known for writing “darkly funny, sometimes surreal, plays that evoke the fringes of American life,” offering wide-ranging opportunities for “serious” actors to essay challenging characters they can sink their thespic teeth into.

Previous incarnations of Shepard’s twisted ode to sibling rivalry had other exciting actors facing off against each other—like Ethan Hawke and Paul Dano, John Malkovich and Gary Sinise, Tommy Lee Jones and Peter Boyle, Bruce Willis and Chad Smith, and Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly.

Is blood really thicker than water? We chuckle at the thought of millennials watching this play about brotherly love and brushing it off with a dismissive quip, “Mukhang hindi naman … ” But setting that jocular thought aside, it was instructive to see how the contrast in Kit and Johnny’s acting styles creates tension that is affecting and alienating at the same time.

Actors Harington (left) and Flynn

Twenty minutes before the lights dim to signal the actual start of the play, Kit takes a seat in front of a table and his typewriter and begins to read a newspaper.

In “True West,” the actor plays Austin, an Ivy League-educated writer who has difficulty completing a screenplay commissioned by Hollywood producer Saul Kimmer (Donald Sage Mackay).

Cash-strapped Austin has a wife and kids, so he has a lot at stake on Saul’s high-profile project. He is housesitting his vacationing mother’s (Madeleine Potter) empty home when his domineering, “good for nothing” older brother Lee, whom he hasn’t seen in five years, comes barging in.

Neither guy is happy to see each other, but when Lee meets Saul, he proposes a story idea that gets Saul interested—but only if Austin agrees to write the screenplay! You can imagine the tension this creates between the seasoned writer and his crass and loudmouthed brother, who’s heretofore better-known as a thief and a drifter.

When Austin refuses, he’s told that Saul has decided to drop his story and is instead looking for another writer to do the script for Lee’s story pitch! Then, all hell breaks loose.

Kit Harington

The play is a thespic showcase for Kit and Johnny, that’s for sure, but the dynamic that develops between the actors goes off-kilter in instances when the latter acts up a storm and “overdoes” his bad-boy bit. Seen individually, there’s nothing wrong with each actor’s portrayal.

But there are things about their disparate styles that don’t complement each other, deftly demonstrating what happens when talented actors, who are tasked to tell the same story, aren’t “on the same page.”