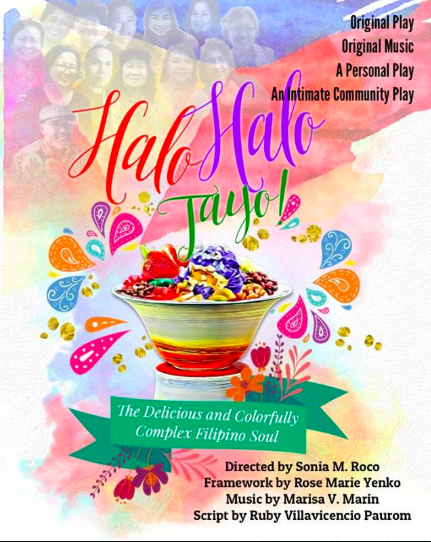

The making of ‘Halo Halo Tayo’: A musical on the complexities of the Filipino soul

Image: Facebook/Carl Jung Circle Center

Halo-halo, as a Filipino term, takes on two intimations, with the more popular one making reference to a shaved ice delicacy of beans, yam, milk and grated coconut, the iconic dessert that imperiously rules the dining table. The other, meanwhile, is an ambiguous if not arguable answer to a just-as-ambiguous interrogative of “What is a Filipino?”; halo-halo therefore can also be the condensed version of the familiar answer, “partly Pinoy and something else.”

Who we are as individuals and as a people is a loaded question pondered about often, as the answers do not come from the easiest of places. But there are lots of ways of arriving at an answer, and the more creative of the well-meaning, meaning-making bunch ought to show that the methodology — after the whys and wherefores — is just as important as the message itself.

Budbud Kabud

For four members of the Carl Jung Circle Center (CJCC), their quest to articulate the Filipino elements within materialized in the form of a musical, “Halo Halo Tayo”, the concept of which was first entertained in the womb of a van, specifically Sonia Roco’s van.

“Halo Halo Tayo” is all set to be staged on June 12, Independence Day, at 4 p.m. in Miriam College, Henry Sy Sr. Innovation Center, Katipunan Ave., Quezon City.

Article continues after this advertisementThe group of friends from Loyola Heights, who call themselves the Budbud Kabud (from the French word boudoir), would often go to meetings and conferences at the CJCC in Mandaluyong, Metro Manila. These chance car rides gave possibility to “Halo Halo Tayo”, an undertaking that transpired in the most unconventional of ways.

Article continues after this advertisement“It did not just come out like an ordinary or traditional way na you have a playwright, you commission him to write a play and then [you perform on] stage,” Sonia Roco told INQUIRER.net last June 5, while sitting inside the office of her husband, the late Senator Raul Roco.

“We would attend workshops through the years, we have been enriching ourselves, so from there Rose would ask the members, ‘What area of CJCC would you like to develop?’”

Rose Yenko is a clinical psychologist, and the co-founder and chairperson emerita of the CJCC. Her question, of what area of the center its members want to develop and what dreams they have yet to accomplish in their lifetime, was what gave rise to an onslaught of ideas.

“Me, I like developmental theater kasi that’s my upbringing,” continued Roco. “The rest [said] travel, food, maraming [a lot of] areas. So when she (Yenko) put it together, what she said [was], ‘Sonia let’s put up a musical.’”

And so, the quest for a musical was born.

Cultural archetypes and the collective unconscious

Except, as with most things, it seemed easier said than done.

“We said okay right away, we will have this play, we’ll write it ourselves, we’ll have the search first, conflict’s in the middle, simple, you know? Beginning, middle, end,” recounted Roco. “Aba, someone said, why don’t we ask Rose Yenko to give us the nine gifts of the Filipino, the characters [for the musical]?”

The nine gifts of the Filipino, from Yenko’s book “The Gifts in the Filipino Psyche”, served as the framework for the musical. The nine gifts pertain to nine Jungian archetypes — universal patterns stemmed from the collective unconscious — whose dominant energies and traits, Yenko postulated, were inherently present in the Filipino.

There is the Artist, the Navigator, the Healer, the Mystic, the Tribal, the Reveler, the Islander, the Warrior, and the Child of Eden — each one unique and significant to its bearer. Archetypes, being a making of the collective unconscious, do not die nor simply fade away as it manifests in everybody through and through — collective just as it is universal.

Beyond the demarcations of language and race, anybody in the world can find and identify with the traits and energies of, say, the Warrior, the Mystic, the Artist, so on and so forth, within themselves.

Ruby Paurom, the scriptwriter of “Halo Halo Tayo”, explained that Yenko’s framework was relevant to her writing process as it gave her the fertile ground for weaving the story together. It was an otherworldly experience that, for lack of a better term, made her “grow arms and legs.”

“It provided windows of understanding to who we are as Filipinos… These [nine archetypes] are very distinct energies of ourselves as Filipinos,” said Paurom. “This [musical] has about nine distinct characters so it’s very challenging, how do I wrap it up?”

Paurom pointed out that the narratives of the nine characters in the musical were inspired by real life stories of friends and loved ones, tackling unique experiences that the viewers themselves may be able to relate to. Moreover, Paurom applied the Greek chorus, which the Greek playwrights used in the olden times to make the story come together.

“This Greek chorus embodied subconscious thoughts which are very much in the Jungian study,” she said. “Carl Jung’s work [was] very much anchored on mythology, and Greeks are very big on mythology.”

From theory to sensibility and praxis

The concept of archetypes and the collective unconscious may seem overwhelming, if not quite esoteric, for those who aren’t well-versed with Jungian psychology. Paurom, however, shared that the professionals behind the CJCC go to great lengths in making these concepts graspable, such as constructing modules and applying them into situational and relatable cases.

“Halo Halo Tayo”, in itself, is a lofty attempt to bridge that gap between the abstruse and what is intelligible, from academia to the commoner, in a scholarly, but laymanized fashion.

Roco also added that “Halo Halo Tayo” is their way of making a change in society, perhaps no matter how big or small, from the corner where they stand.

“We are working towards social transformation, that’s what we all want. But here, the assumption is we all have our ‘gold.’ We have not taken care of our ‘gold’ with all this wounding, so the message is if we want social transformation, let’s dig up and claim that ‘gold,’” Roco said.

Meanwhile, Yenko argued that the Warrior archetype Filipinos embody has been far overused — and it’s a sensible insight when one tries to perceive how far Philippine society has come and how far it has yet to go. Perhaps it’s just about time the Filipino tapped into the rest of its potential by harnessing the other archetypes within them.

“The Warrior archetype, that’s already gasgas (overused),” Yenko said. “It is still needed, but we are not tapping the full richness of our capabilities. [Filipinos] are not just Warriors, we are beyond [that]. My battlecry has always been the Artist. The Artist is the next hero. The creative process is gonna be the next heroic process apart from that Warrior battlecry which is the heroic process [we] know. But for me it’s the Artist, the creativity of the Artist.”

It’s a daunting challenge to do away with the old and look inward in search of something new, something untried. But it wouldn’t be so formidable if only people weren’t so afraid to explore the depths of their self, and realize that there is more power to them than what they initially know.

This is the aim of “Halo Halo Tayo”, a community musical that first started off with friends unassumingly throwing ideas inside a moving van before eventually transforming into a pursuit of social change through an unorthodox, self-reflective approach.

Such aspiration in unsheathing the enigma behind archetypes is noteworthy, more so as it is in the intention of better understanding the Filipino as an individual and as a whole. And yet, no one else apart from the members of CJCC seem to be making such unflinching attempts. Clearly, it’s a combustion of varied energies from the intricacies of being; one that goes depths below depths into the unconscious, an animating principle that, upon further examination, only reveals an unstoppable and undeniable force. JB

RELATED STORIES:

OFW’s creative upcycled gowns featured in PH consulate, wow Hong Kong locals

Likhaan 11, or why we must start this year reading Philippine literature