Movement fuses popular musical genres with socially relevant content

During the recent opening of a small, nondescript bar in Quezon City, a local group called Pordalab held court before an intimate crowd. “Sumabay, sumabay, sabay-sabay sa pag-awit,” the group’s front man Karl Ramirez and vocalist Boogs Villareal chanted in unison over danceable, digital-sounding beats that reverberated across the packed room.

Midway through the number, the music swelled into a soaring pop-rock anthem. The song, “Ngayon ang Panahon,” easily sounded like something one would expect to hear on mainstream radio. But unlike the hits that currently saturate the airwaves, Pordalab’s piece tackled a different kind of affection: love for the country.

A rallying cry that implores listeners to effect change, “Ngayon ang Panahon” is a composition that could be described as a “public interest song”—an umbrella term that refers to patriotic, revolutionary or progressive music.

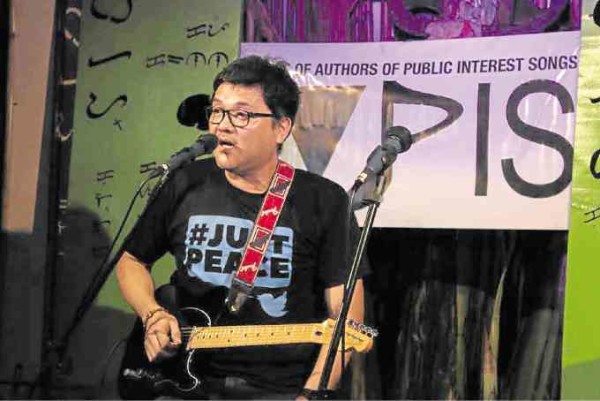

Though such music genres are traditionally associated with march, acoustic or folk sounds, things do not necessarily have to remain that way, especially today, pointed out Ramirez, who is the outgoing executive director of the League of Authors of Public Interest Songs (Lapis), a group of musicians, whose goals include the cultivation and promotion of musical works that highlight the issues that beset the country and its people.

“We felt the need to have a music movement that would fuse socially relevant content with musical styles and genres that are popular with the youth,” Ramirez told the Inquirer. “Whenever we embark on a project or write a song, we try to identify our target audience or age group, and figure out what they like or do not like.”

This artistic direction was duly reflected in “Mag-alay sa Bayan,” a compilation of 16 public interest tracks crafted by Lapis members, who are led by the organization’s founders and officers: Gary Granada, Bayang Barrios, Chikoy Pura, Lolita Carbon and Cooky Chua.

“Mag-alay sa Bayan,” one of Lapis’ most important accomplishments thus far since its creation in November 2014, features songs that delve into such topics as women empowerment, the pursuit of peace, the importance of teachers in society, and the plight of migrant workers.

While some songs like “Katribo Ko” (Barrios and Naliyagan)—about the discrimination indigenous peoples face—uses a more traditional sound and ethnic instruments, there are others that exude a contemporary vibe or sensibility: “Tambay Prototype” (Jimmy Melendrez) about underemployment of fresh graduates, uses hip-hop influences; “Cancer” (Plagpul) a commentary on the mediocre state of health service in the country, is set to a funky, alternative rock tune.

“The album is a product of seasoned and young music artists. The track list is strategically curated; we made sure that the songs are rendered in different styles, and that there is no duplication of subject or theme. I believe that even millennials would find the music appealing,” Ramirez said.

According to Ramirez, who is likewise a coordinator of Musika Publiko—another group that shares the same advocacies as Lapis—since progressive musicians do not enjoy the same type of machinery that their mainstream counterparts have, banding together is imperative for them to be heard.

“Having a group like this is beneficial to all of us, because we get to pool our resources and help each other out when it comes to recording, packaging or distributing our works. Without a platform, some of these tunes would likely stay unrecorded or played only in our respective gigs,” he said. “We do not have a mainstream platform.”

“This musical movement for public interest songs is not new; it has been there since the martial law years, even earlier. But we believe that there is muscle in numbers, and it is good that there are programs that help execute this vision,” Ramirez said of Lapis.

Outside the album, Lapis is steadfast in its support for its members’ and their own musical contributions. Among the more timely tunes to have come out of the organization’s network of artists in the past few months are the rock band Plagpul’s “Apo-Apologist,” which takes a humorous dig at young fans of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, who rely on internet memes as sources for discourse.

Another one is singer-songwriters Dedong Marcelino and Ada Marie Tayao’s “Mata sa Mata,” a harrowing ballad about extrajudicial killings.

“I have been to some of these young artists’ gigs, and it was heartening to see that a lot of the people who watched them are millennials, and are not necessarily activists,” Ramirez said, adding that “a good number” of Lapis’ 78 members are young artists. “For us, it only means that writing public interest songs is not dead; there are many up-and-coming musicians who want to continue this movement.”

Lapis conducts songwriting workshops and mounts fundraising gigs for the benefit of Filipinos in need, such as the lumad, and the farmers affected by the drought in Kidapawan in North Cotabato last year.

Ramirez hopes to see Lapis push through with its goals. “We want to teach young musicians how to compose and make music enjoyable,” Ramirez said. “We want to convey the message that anyone can immerse himself in our society—walk the streets, talk to the people, look at our environment—and write songs about it.”