War, passion mark ‘Hemingway & Gellhorn’

LOS ANGELES — HBO’s “Hemingway & Gellhorn” is a vibrantly smart, sensual biopic due to its game stars, Clive Owen and Nicole Kidman, and in larger portion to filmmaker Philip Kaufman.

Kaufman, the big-screen master behind “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” and “The Right Stuff,” is making his TV debut (9 p.m. EDT Monday) with an account of the ill-fated romance of Ernest Hemingway and journalist Martha Gellhorn during the tumultuous 1930s and ’40s.

The film’s embrace of political, artistic and sexual passion is the result of Kaufman’s own ardor — especially for women, according to Kidman.

“I love him. I love that he loves women, and he REALLY loves women,” she said. “He was the one that brought the sexuality to the piece. … He’s made great movies, and for him to want to tell this love story — that’s his forte.”

Gellhorn, a leggy blonde who was as gifted and tough as she was beautiful, proved more than a match for the charismatic, driven novelist celebrated for works including “The Sun Also Rises” and “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

(He’s also mocked in some quarters for his he-man persona, the most recent jabs coming from Woody Allen’s “Midnight in Paris.”)

“Hemingway & Gellhorn” depicts her transformation into a renowned and empathetic war correspondent under Hemingway’s tutelage, while he gradually descends into alcoholism and inertia that he blames in part on her growing independence.

“If they had lived together in a slightly different time, they might have stayed together,” Kaufman said, perhaps wishfully. “They might have found a way if there’d been more breathing room.”

Setting its oversized characters on a vast historical stage that includes the Spanish Civil War and World War II, the film follows them from their sparks-fly first meeting in a Key West, Fla., bar to Gellhorn’s decision to choose her career over him and their marriage.

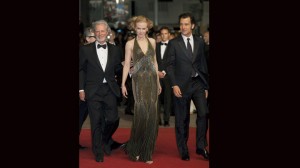

From left, director Phillip Kaufman, actors Nicole Kidman and Clive Owen arrive for the screening of Hemingway and Gellhorn at the 65th international film festival, in Cannes, southern France, Friday, May 25, 2012. AP/JONATHAN SHORT

In between, the pair dodge bombs and bullets that at times serve as a dangerous backdrop for their sexual encounters (played with gusto, and a fair amount of nudity, by the film’s stars).

“It’s about storytelling, what was necessary to show the heat that existed between them and especially in the heat of war,” said Kaufman.

The veteran writer-director, now 75, knows how to make the screen smolder, bare skin or not, and how to portray strong women, including astronauts’ wives (in “The Right Stuff”) and writers like Gellhorn and Anais Nin (in his film “Henry & June”).

Kaufman’s age “doesn’t come into it,” Owen said. “His spirit is about 25.”

“He knows how to put together a story. It’s a big challenge to do a relationship, travel to all these places, and keep them in front of the epic backdrops of the Spanish Civil War, China, and do it effortlessly and fluidly,” Owen said.

The project also owes a debt to James Gandolfini (“The Sopranos”), who pulled out his checkbook to provide script development money, said Alexandra Ryan, one of the film’s executive producers.

Making a grand drama on a TV budget (albeit a generous HBO one) required artful use of the San Francisco area as stand-in for Europe and elsewhere. Working with longtime collaborators including editor Walter Murch and production designer Geoffrey Kirkland, Kaufman also employed “green screen” technology to insert actors into period footage, adding further theatrical sweep.

The Cannes Film Festival recognized the achievement, creating a rare berth this week for a TV movie.

“It’s a great honor,” said Kaufman, who first showed a film at the French festival nearly 50 years ago.

Owen, who packed on weight to play Hemingway, was Kaufman’s pick for the hypermasculine writer both because of the actor’s talent and “his testosterone count. He definitely had it,” Kaufman said.

The British-born Owen was a bit wary of playing a famed American, but the script and Kaufman’s reputation sold him. Owen immersed himself for months in all things Hemingway to capture the man and his relationship with Gellhorn, including their correspondence.

“If you read the letters, they were epic, romantic, beautiful, and they were pining for each other,” Owen said, adding that the film’s dialogue reflects both Hemingway’s work and the couple’s own intimate exchanges.

Kidman, who plays Gellhorn as a young woman and in her later but still energetic years, said she finds appeal in women “who push the boundaries. I’m very attracted to them because we need them as role models.”

“We were dedicated to giving her what we felt was the story she deserved,” Kidman said. “She’s very prickly at times, and had a strong sort of male side to her where she can exist physically in war. … I loved that side of her, and I’ve never done that on screen before.”

For Kaufman, the film provided an oblique way to pay tribute to his adventurous and “outspoken” wife of 52 years who died of cancer in 2009. “That was Rose,” a friend told Kaufman after seeing Kidman’s portrayal.

Kaufman laments that Gellhorn’s accomplishments and bravery, so celebrated in her life, have faded from view: She and Hemingway, two superb writers if mismatched or mistimed lovers, both deserve attention and respect, he said.

The 89-year-old Gellhorn, beset by ill health, ended her life in 1998, long after the depression-afflicted Hemingway killed himself in 1962 at age 61.

“Who knows what Martha would really have thought (of the film), or Hemingway,” mused Kaufman. “But I’m glad we could give this gift back to them.”