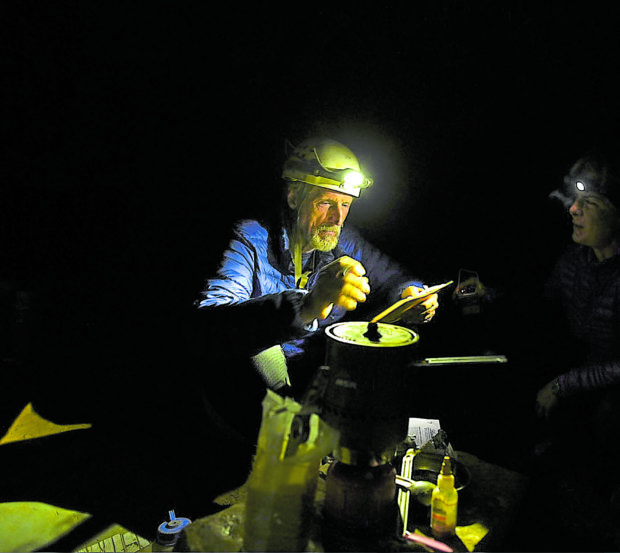

Cave explorer Bill Stone takes viewers deep beneath the earth

Truth may not always be stranger than fiction, but National Geographic (NatGeo) Channel’s “Explorer: The Deepest Cave,” which will be shown at 4:10 p.m. today, demonstrates that it is at least more fascinating or visually compelling.

The hourlong documentary follows renowned cave explorer Bill Stone as he embarks on a lifelong quest to go deeper beneath the earth than any human has ever ventured. He has led expeditions for more than 50 years of his life.

Deep in the unexplored abyss of Cheve Cave in southern Mexico, Bill’s goal is to set a new world record by finding a passage beyond a depth of 7,208 feet. In comparison, Veryovkina Cave in Eastern Europe is 7,257 feet deep.

It’s an expedition that has been compared to climbing Mount Everest—but in reverse—intended to prove that Cheve is the deepest cave in the world.

For the 2021 leg of his decades-long latest underground adventure, Bill spent three months over 12 miles of tight, twisting and claustrophobia-inducing passages. But the will to conquer the cave will push him and his never say die team to the absolute limits of survival and sanity.

Article continues after this advertisementLast week, we got the eloquent 68-year-old explorer to give us the comprehensible lowdown on the Sistema Cheve expeditions that he championed between 2004 and 2021—which led to the discovery of nearly 100 kilometers of subterranean tunnels.

Article continues after this advertisementWe told Bill how the film made us feel like a ringside spectator of a gorgeously shot blockbuster film whose spectacular images would be hard to replicate even by the most modern computer-generated imagery.

But what does he expect to find at the bottom of those deep caves and sinkholes?

“This is a question that we’re always asked by the people who live in these areas,” Bill said. “The classical question when you show up for the first time is, ‘Are you looking for gold? For oil? For artifacts? Why are you here?

“The only thing you’ll find underground is water, rock, sediment that gets carried in, and occasionally a few small creatures. The farther you go, the less there are of them because there’s less energy.

“So even at the very bottom of the cave, we might see, for example, tiny isopods—something people call springtails—which are little multilegged creatures that are about a millimeter in size. They are whatever gets washed in during the rainy season, like organic debris from the surface, and that’s it. Otherwise, it’s a lifeless environment down there.

Director of Photography Kasia Biernacka checks out an illuminated crystal

formation inside Cheve Cave

“The only thing that exists there, by the way, are fungus spores that get carried in by the wind. So if you leave a bit of uneaten food for a week, it will be full of fungus when you come back. But we usually try to stay pretty clean while we’re down there.”

Our Q&A with Bill:

The way this film was shot, it felt like you were taking your viewers with you while sparing them from the distraction of seeing the cameras. Could you talk about the logistical side of filming this and capturing those stunning images?

That’s a really good question. It was actually one of our biggest concerns, because I’ve done this a lot. I’ve been leading expeditions for over 50 years and spent 10 and a half years of my life on actual expeditions.

Anytime you bring a film team along, the first thing that everybody in the regular team will say is, “How will it impact our ability to do the job that we came here to do?” In the old days, it was serious business because just taking lighting underground became a big distinguishing aspect. It is completely dark down there, so you really have to light it up. So, you have a big 16mm film equipment, cinematography lights or car batteries that people had to carry up and down a rope.

What changed in the last five or six years was the availability of nongrainy, high-performance cameras that could shoot at super low-light level and still bring back very sharp images. Completely eliminated was the problem of the power that we needed to drive the cameras and the batteries. We still had the problem with carrying the cameras, which were still sizable—and there were always problems with fogging.

But the flipside to that was, who was operating those cameras? In the past, we’ve always argued with the networks that it should be a member of our team and so we have Kasia Biernacka, who isn’t just a world-class cinematographer, but also happens to be a world-class cave explorer. She has worked with us for over 20 years. She was kind of our anticipated lead.

But National Geographic suggested to have their professionals come with us. They came over to have a meeting with us in Texas, where we assessed where they had come from. They all had stellar backgrounds—they had climbed Mount Everest multiple times, and also spent filming in Antarctica. Some of them had climbed Denali, the highest mountain peak in North America, over 30 times, so they were all Yosemite-class rock climbers—but they weren’t cavers.

So, we gave them a crash crossover course on how to deal with ropes underground, because the difference between Yosemite or Everest and what we deal with is dramatic. There are over 12,000 meters of rope rigged in Cheve. It’s a different world where you’re carrying heavy loads—20 kilograms are a standard load on ropes—for 14 hours a day.

They attended a boot camp and learned to be expedition cavers. To their credit, [Emmy-winning director] Pablo Durana and the others from NatGeo really came through. Everybody on the expedition was impressed by how rapidly they adapted to being there and understanding that it was their responsibility to carry their fair share of the load. They were in top shape and the interference, in my opinion, was minimal. The result is what you see.

What sort of technology and resources would your team need to continue this mission?

As of 2017, the technology that we needed was [focused on] how to get beyond a long underwater tunnel, which was at the end of the known cave at the time. Over the course of 40 years, we had invented a closed cycle life-support diving equipment, and we used our own equipment there in 2017. In the same year, we discovered the bypass to these underwater tunnels—which got us out to where we are right now.

If you ask what the limiting technology is right now, I can tell you directly that it’s the logistics of just allowing people to live out there—and part of it is power. Everything we do runs on electrical devices. So, how do you get power at this incredibly remote place?

Right now, we have several engineers working on building the world’s smallest microgenerator—a gasoline-operated device that’s half the size of a loaf of bread—which will put out 200 watts, and charge our main batteries overnight. This power is one-third of the equation.

The second-third is food. How do you cut the weight of the food without having a crew that is not powered sufficiently to do their job? We burn over 7,000 calories a day, which is more than those at the Tour de France—and we do it for months. If you lose too much weight, your body will start to burn protein—and your heart is protein. So, it’s a dangerous thing to not eat enough.

We have to keep finding food that’s more energy-dense, more calories per gram or per cc, really. If there was a tablet that we could take that would give you 7,000 calories per day, we’d be on it (laughs), but it doesn’t exist. So we keep inventing new ways to compress food.

And the third one is the equipment that we use. How do you cut down the weight and use smaller diameter ropes? Can we use titanium, instead of stainless steel for our rigging? Things like that.

Ultimately, with our current technology, we can maybe get to two more camps beyond where we are right now. At that point, nobody knows if it’s possible to continue further without jeopardizing the safety of our people.

Are there other caves you want to explore, perhaps from Asia or Europe?

The short answer to that is no. What has become the interesting challenge is how deep you can go. There are gigantic caves in Asia, but they aren’t all that deep and not all that difficult to explore. There are deep caves in Europe, but you can only spend so much of your life going to different directions and not accomplish anything.

So, I’ve chosen to focus on trying to solve this problem at Cheve. If we succeed and finish it, well then OK, I can think about what the next project is.

Are there other unticked items on your bucket list?

Yeah, we’ve got some very crazy ones out there. We have designs at my company for spacecraft, for coming back from orbit that are quite different from what our views are right now. We have long-range plans for how to utilize lunar resources.

And under development now are very long-range autonomous underwater vehicles that, at the very least, are going to replace cave divers in the next couple of years. INQ

Watch “Explorer: The Deepest Cave” on National Geographic Channel (channel 41| 195 on SkyCable) at 4:10 p.m. today.