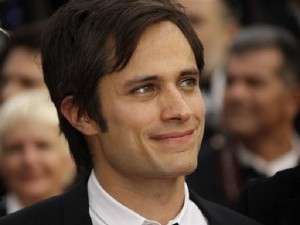

In this May 12, 2010 file photo, actor Gael Garcia Bernal, arrives at the premiere for the film “Robin Hood” at the 63rd international film festival in Cannes, southern France. Chile gets its first shot at an Oscar for best foreign-language film with the Academy’s nomination of No. The Mexican actor stars in “No,” which revisits a publicity campaign that helped oust Gen. Augusto Pinochet from power after 16 years of his brutal regime. (AP Photo/Joel Ryan, File)

SANTIAGO, Chile — Chile is getting its first shot at an Oscar for best foreign-language film, along with global attention and a boost to its thriving film industry with the nomination of “No.”

News of the film’s nomination Thursday was widely celebrated by Chileans, but also had been expected by many since the movie became a surprise hit at Cannes.

“No” revisits a publicity campaign that helped oust Gen. Augusto Pinochet from power after 16 years as a dictator.

Gael Garcia Bernal plays Rene Saavedra, a formerly exiled advertising hot shot drawn into a 1988 referendum TV campaign who tries to persuade people to vote “No” to eight more years of Pinochet.

Selling the idea that positive change could end the regime, his character uses ads that feature catchy jingles, a rainbow graphic and dancing Chileans in a variety of guises — from cowboys and housemaids to cooks and miners.

“I had a great time doing this,” Garcia Bernal said in a telephone interview with The Associated Press from Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, where he’s filming a short with his close friend and fellow actor, Diego Luna, in collaboration with Chivas Regal whisky.

“The fact that I played an exiled man is something very common in Chile because the dictatorship provoked this type of returns,” he added.

The ad campaign worked in real life. Pinochet, who once compared himself to the best Roman emperors, was ousted when 55 percent of people voted “no” to continuing his rule. His removal paved the way for Chile’s return to democracy and more than two decades of economic prosperity.

“Dictators are not usually ousted through democratic elections, and this is a profoundly human story, which was resolved through things that have to do more with beauty than with horror,” director Pablo Larrain told the AP.

Larrain said he’s excited about the nomination because it will entice more people to see the story of one of Chile’s most memorable moments.

“The movie shows how society organized and changed the destiny of a whole country, how a dictatorship was defeated through peaceful means, positive ideas,” Larrain said.

The film’s July premiere in Santiago unsettled many audiences because Chile remains deeply divided over Pinochet’s rule.

Even the mention of his name makes many Chileans cringe with memories of the dictator shutting down Congress, outlawing political parties and sending thousands of dissidents into exile, while his police killed an estimated 3,095. But to his loyalists, Pinochet remains a fatherly figure who oversaw Chile’s growth into economic prosperity and kept it from becoming a socialist state.

“The movie shows how Chile through the referendum negotiated with Pinochet because we kept his model to the point where we’ve abused a model imposed by Pinochet,” Larrain said.

“We negotiated with him because we were never able to judge him, and Pinochet died a free man and a millionaire.”