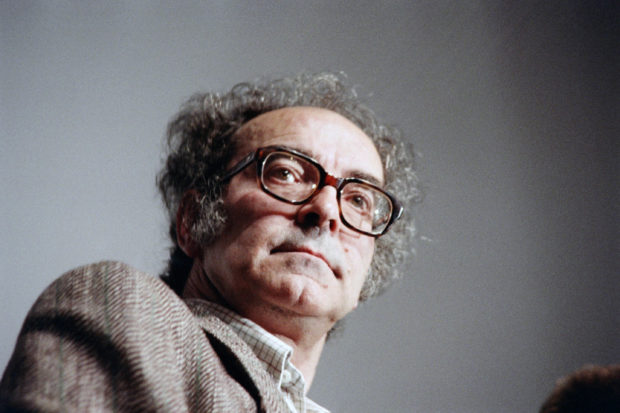

In this file photo taken on May 21, 1988, Franco-Swiss film director Jean-Luc Godard attends a press conference during the Cannes International Film Festival in Cannes. Image: AFP

Jean-Luc Godard, who has died at 91, was the rebel spirit who drove the French New Wave, firing out a volley of films in the 1960s that rewrote the rules of cinema.

Between “Breathless” (“A Bout de Souffle”) in 1960 and the student protests of 1968, Godard exhilarated audiences as he shook the film world with his technical innovations and savage, occasionally lyrical, satires.

Sometimes working on two movies at the same time, he ranged over crime, politics and prostitution in a burst of creative energy that would inspire two generations of directors.

Godard’s witty aphorisms like “a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end — but not necessarily in that order,” became lodestars for filmmakers from Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson.

But the flame that had burned so bright in the 1960s veered off into revolutionary politics and Maoist obscurantism in the 1970s, and he came to be seen almost as a tragicomic figure.

Godard spent several years experimenting with video before returning to commercial filmmaking, of a kind, in 1979.

Modern prophet

But the freshness was gone and critics accused him of becoming too elliptical, with some branding his early films misogynist.

Yet the increasingly reclusive Godard persevered down his singular path, before reinventing himself in his later years as a gnomic cigar-chomping prophet.

He shot his critically acclaimed “Film Socialisme” on board the Costa Concordia cruise ship in 2009, declaring that capitalism was heading for the rocks. When the ship ran aground three years later, it wasn’t just his small band of disciples who treated him as a visionary.

Born in Paris into a well-to-do Franco-Swiss family on Dec. 3, 1930, Godard was lucky enough to spend World War II at Nyons in neutral Switzerland, returning to the French capital in 1949 to study ethnology at the Sorbonne.

But his real education was in the little cinemas of the Latin Quarter where he first ran into Francois Truffaut, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer, all future luminaries of the French cinema.

He fell in love with American action cinema and began writing criticism under the pseudonym “Hans Lucas” with Truffaut, Rivette and Rohmer for small magazines like the Cahiers du Cinema, where they plotted to revolutionize the art.

After a failed attempt to make his first film in America, he went to work on a dam in Switzerland and saved enough money to make a film about it, “Operation Concrete” (1954).

It helped lay the foundation for his rapid ascent that would see him hailed as the leader of the French New Wave when “Breathless” was released in 1960.

‘The Picasso of cinema’

That swaggering story of a small-time crook on the run who romances a young American in Paris was a major landmark in French cinema, heralding the arrival of a generation of irreverent young filmmakers determined to break with the past.

So big was its impact that Truffaut called Godard cinema’s Picasso, someone who had “sown chaos… and made everything possible.” As often with Godard, their friendship later turned sour, with Truffaut branding him as “shit” after the pair fell out in 1973.

By shooting on the fly in outdoor locations and improvising endlessly, Godard rewrote the rulebook and helped popularize the idea of the director as “auteur,” the creative force behind everything on the screen.

“Breathless” also gave the first big break to Jean-Paul Belmondo, who would later star in Godard’s masterpiece and most personal film “Pierrot le Fou” (1965), which explored the pain of his break-up with the Danish actress Anna Karina.

From the start, Godard’s career was dogged by controversy. “Le Petit Soldat” (1960), with its references to the Algerian war, was banned by the French authorities for three years and “Une Femme Mariee” (A married woman, 1964) had its title changed from “La Femme Mariee” by censors concerned that its adulterous heroine might be taken for the typical French wife.

But after “Weekend” (1967), a gory examination of the obsession with cars scattered with surrealistic traffic accidents, his work too often appeared self-indulgent.

Indeed, Godard became something of an intellectual oddity, emerging every few years from his bolthole in Rolle on the shores of Lake Geneva to lob a verbal grenade or two.

It was this tragic, cartoonish Godard on the slide who features in “Godard Mon Amour,” the 2017 comedy about him by Michel Hazanavicius, the Oscar-winning maker of “The Artist.”

But by then Godard was having the last laugh, with his reputation somewhat restored by a series of low-budget metaphorical films that questioned our image-saturated world.

“Film is over,” he told The Guardian in a rare interview in 2011, recanting his oft-quoted maxim that “photography is truth, and the cinema is truth 24 times per second.”

“With mobile phones, everyone is now an auteur,” he said. JB