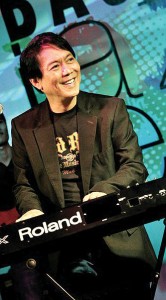

This Boy won’t stop playing

Boy Katindig of the famous clan of jazz musicians is back after being away for almost 30 years.

In 1984, at the peak of his career as a recording artist and performer, he packed his bags and went to Malaysia, then to the United States, where his reputation grew by playing with highly regarded musicians.

With his return, the talented son of legendary pianist Romy Katindig is doing his share in reviving the local jazz scene by holding a nationwide songwriting competition.

He had a chat with the

Inquirer a few days ago:

What was the local scene like before you left? Why did you leave in the first place?

I didn’t like what was happening then. Punk rock and new wave had become the “in” thing. Radio, my only medium for new songs, was changing—the jazz station WK-FM was reformatted. The Manila Hotel, where I was playing, was being boycotted as a result of the rallies leading to the People Power revolution. My father, who was already in the States, suggested that I go there and see if I would click with a different audience. I initially tried my luck in Malaysia, where I wrote more new songs.

How did things go in Malaysia?

It was a dream come true. I was initially offered a lounge duo gig, where we played straight fusion and standards. The owner of the hotel where I was performing thought I deserved something of my own. Within two weeks, he put up another club, named it The Manhattan, and had me tap the best guys in town to form my own band. That was what I really wanted! We named the band The Waves and introduced the first fusion club in Kuala Lumpur. We backed up John Kaizan Neptune while he was there, and I was getting offers to work as musical director for some of the top KL bands. I stayed for two years, then went to the States in 1986 upon my father’s prodding.

Your father seems to have played a huge role in your journey as a musician.

Yes, he did! He had uncanny foresight. When he founded Katindig Brothers, he got them in all of his gigs. Eddie Katindig started by playing bongos with him. My dad was open to contemporary music though his first love was jazz. He listened to Sly and the Family Stone, Blood Sweat and Tears, Tower of Power. He encouraged me to listen to these bands, feel their groove, learn their style. After feeding me popular stuff, he threw in Chick Corea and Cannonball Adderley. I was only 13. He introduced me to the music of organ player Jimmy Smith, whom he idolized.

How did you penetrate the US jazz scene? Who was the very first American jazz artist you collaborated with?

In 1987 I formed my own band in Los Angeles; we played fusion Wednesday nights. Rippingtons percussionist Steve Reid, who wasn’t known yet at the time, checked out the gig for a possible slot in my band. Mike Baker, who used to work with Whitney Houston, and Stanley Smith (of Jeffrey Osborne) both played drums for me. Mark Van Wagenigen of Ray Obiedo and Dwayne Smitty Smith played bass. Allen Hinds of Randy Crawford and Down To the Bone played guitar. In 1993 I produced the album “In Time,” in which I played alongside Abraham Laboriel, Russ Freeman, Brandon Fields, Brenda Eager (of Luther Vandross) and Gerald Albright.

But it was Michael Paulo that I did major collaborations with. We met while I was doing gigs in Hawaii with a band called Aura. Turned out, he had heard one of my CDs, “Journey to Love.” He said he was looking for Asian musicians, particularly Filipinos, to collaborate with, as he was forming his own label, Noteworthy Records, based in Seattle. He called to say he wanted to sign me up. That’s where it started. He also collaborated with producer Blue Johnson, who managed Seawind. That was in 1995. I got a juicy deal to play at the Bellagio in Las Vegas in 1999. That lasted for two-and-a-half years. I was a recording artist and doing gigs at the same time.

What lessons have you learned as a musician and as a person?

A lot of things happened in-between KL and the US, like changes in my personal and professional relationships. It’s never been a perfect life. I believe fate led me to all those experiences.

Staying humble and focused are just some of the values I’ve learned on my journey, both as a musician and as a person. Being a musician is about life, not just about music. It’s also all about having relationships, having a family. One has to strike a balance. I also had to learn about the music business.

On the other hand, the biggest challenge was finding my identity. During my gigs I always inject some of my own songs. I mix them in-between straight jazz pieces. When people ask, I simply say those are part of my original work.

I learned to accept that economics plays an important role in shaping one’s career. One needs to be a businessman and adjust. It’s also about knowing what will sell with your audiences.

What do you think of the current state of jazz in the country?

It’s no longer as it was during our time. It was at its peak in the 1980s, when you suddenly see David Benoit in the audience; or Ronnie Laws walks in while you’re playing; or the whole band of Al Jarreau jams at Vineyard. Back in the day, there were long queues at the venue during weekends. There was a time when Manila was a virtual jazz mecca. Now … we’ve practically been overtaken by our Asian neighbors like Indonesia, where they hold the Java Jazz fest annually. I believe it’s because they love their own [music] and the government supports musicians.

Radio plays an important role in promoting the music. Unfortunately, radio stations that used to play our stuff no longer exist. There appears to be some kind of fragmentation within the community. There are differing opinions about what jazz really is. Back in the day, there was more cohesiveness.

How can you contribute to its revival?

With this competition, once we discover new talents, I can take them under my wing, promote them, sign them up to a recording contract, maybe even have them guest in my own album.

They have to submit one original composition and a cover of an original jazz piece. Aside from a record deal, they will also get to do gigs with me.

We’re planning to promote this nationwide, maybe do a road show or campus tours.

Hopefully this will snowball into something big. My dream is for young talents to shine, and not just end up as front acts for established performers.

This is my way of encouraging the youth to tune in to jazz and hopefullydevelop a passion for it.

(Log on to the Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/TheBoyKatindigJazzCompetition, or call 0918-9301945 and 0917-8509636. Deadline for submission of entries is June 15.)