K-dramas face challenges in transnational streaming era

Actor Park Eun-seok plays Alex Lee in a scene from “Penthouse 3.” Photo courtesy of SBS via The Korea Herald/Asia News Network

SEOUL — As more and more viewers around the world watch South Korean dramas on streaming platforms, the industry faces critical challenges that must be met if it is to continue to expand overseas.

In an era of transnational streaming, cultural sensitivity has become an issue for content creators around the world. Korea is no exception, and Korean dramas have drawn criticism in recent weeks for racial and cultural stereotypes.

The producers of two popular SBS TV dramas, “Penthouse 3” and “Racket Boys,” recently apologized after overseas viewers complained about discriminatory portrayals.

The fifth episode of “Racket Boys,” which aired June 14, centered on a fictitious international badminton competition in Jakarta, Indonesia.

“The accommodation qualities are terrible,” says the manager of the Korean team, referring to the facilities in Indonesia, “and they practice in dome stadiums while asking us to practice in worn-out arenas with no air conditioning.” A scene from the same episode shows Indonesian fans booing players from other countries who have defeated the Indonesian team.

Article continues after this advertisement

A screenshot of comments posted on SBS’ official Instagram account under its “Racket Boys” post (SBS’ official Instagram account)

Indonesian viewers criticized the SBS drama online, and the team posted a message of apology on its official social media account. The message said the show had not intended to insult any particular country or its sports players. It also apologized to Indonesian viewers for any “discomfort that some scenes may have caused.”

Article continues after this advertisementHyun Hae-ri, CEO of Muam, a media consulting and production company, said it was extremely difficult to draw the line in fictional dramas between creative elements and culturally insensitive depictions.

Concerning “Racket Boys,” Hyun told The Korea Herald it was common for home team fans too boo their opponents, whether international or local. “It’s about how fans interact in typical sports match scenes, and it just happened to be Indonesia this time.”

Hyun added that Indonesian fans watched K-dramas closely, and that the show’s producers were unaware of the backlash that could arise from its “unexpected popularity among certain international viewers.” Such popularity is a positive development and should be taken into consideration when creating content, Hyun said.

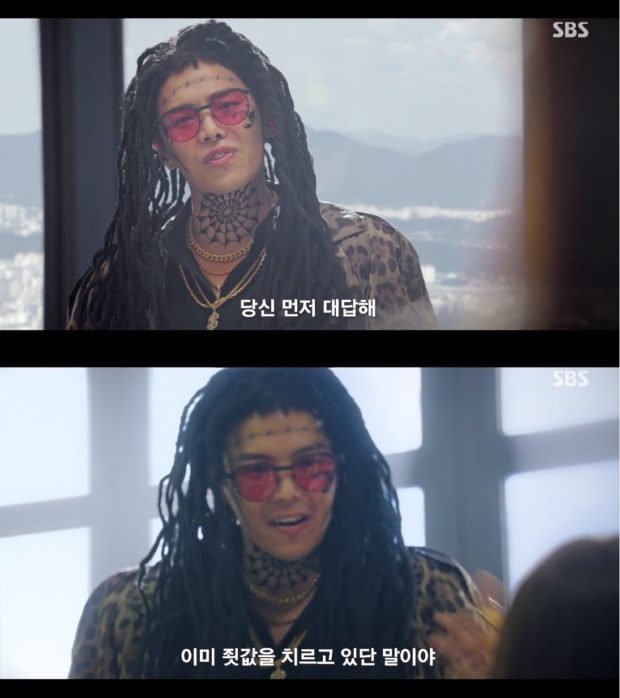

The second episode of “Penthouse 3” — featuring a character named Alex Lee, the brother of Logan Lee from “Penthouse 2,” both played by actor Park Eun-seok — was met with fury and accusations of cultural appropriation.

In the episode that aired June 11, Alex is seen wearing gold teeth grills, dreadlocks, rugged clothing and a big tattoo on his neck. Alex’s appearance sparked immediate controversy, with thousands of social media posts criticizing the drama for playing on stereotypes of African Americans. Some posts mentioned Alex’s accent, condemning it as obvious mockery of African Americans.

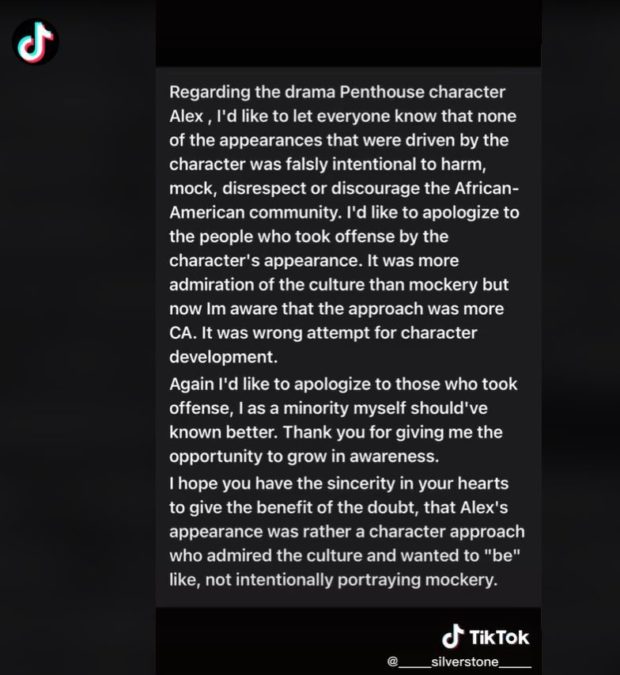

Park posted a letter of apology in English on June 13 on his TikTok account. “It was more admiration of the culture than mockery but now I’m aware that the approach was more CA (cultural appropriation),” Park wrote, adding that he should have known better and thanking viewers for the opportunity to grow in awareness.

In a previous TV show appearance, Park said he had moved to the US with his family when he was 7 and lived there until age 22, when he returned to Korea to pursue acting. The production team of “Penthouse 3” also issued an official apology.

Recent developments have raised the need for content creators to consider how to deal with potentially culturally sensitive topics and scenes. The growing consumption of content on streaming platforms and social media means that Korean dramas and content are being watched by viewers around the world and content creators need to be cognizant of the sensitivities of the global audience.

A post by actor Park Eun-seok on his personal TikTok account (Park’s TikTok account)

“I think it is not just the ignorance and insensitivity of production companies that is revealed through media contents, but is a nationwide problem in which South Korea still lags behind compared to other countries,” Heo Chul, a film director and professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, said in a video interview with The Korea Herald.

The K-drama industry is facing an important transition period, according to Kim Ok-young, a documentary writer and judge for the Baeksang Arts Awards’ television category.

“Rather than creating a top-down government-led advisory body or an association of experts to monitor and filter shows before they are on air, I think it’s much more desirable to put the contents out to the world and open them up for public evaluation,” Kim told The Korea Herald. In the long run, the writer added, this process will help improve the nation’s awareness of cultural, gender, religious and ethnic diversity issues.

TV broadcasters and programs have offered varying responses to the online criticism, with some using the languages of the countries that they may have offended when issuing apologies.

“I still believe that giving full autonomy to the staff in the pre-production process, from developing scenarios to creating fictional characters, is a priority that should be protected and not disturbed,” Lee Yu-shim, a TV producer at KBS, told The Korea Herald.

Lee said producers today, including her, understand that being aware of cultural cues is important to a show’s commercial success.

Heo of Nanyang Technological University suggested that having diverse people on the staff could minimize unintended errors. If a Korean drama wants to introduce a Hindu character, for example, the producers need to cast at least a few writers who are of that religious background, to prevent errors in depicting the character, Heo said.

“The lack of understanding of cultural diversity issues is a problem that both the domestic viewers and creators of the show should together make efforts to tackle,” Heo said.