Thematic pertinence, technical skill merge in Singapore film fest’s PH entries

(First of two parts)

While some of the entries to the 2020 edition of the Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) held recently had physical screenings, the prestigious cinematic showcase founded in 1987 went predominantly virtual this year.

But that hasn’t dissipated the enthusiasm and excitement of SGIFF’s festivalgoers, as well as the participants of this year’s Singapore Media Festival.

We attended the 11-day media fest hosted by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) because we were intrigued by its all-encompassing reach and scope, which, other than the SGIFF, also include the Asian Academy Creative Awards (AAA), the Asia TV Forum & Market (ATF) and ScreenSingapore (SS), and this year’s new addition, the inaugural SuperGamerFest (SGF).

Despite the challenges brought about by the pandemic in organizing this humongous endeavor, Howie Lau, assistant chief executive of IMDA’s Media and Innovation, explained why his team decided to soldier, underscoring the importance of the festival and media in general.

“This is as a result of creativity and determination, of the community coming together,” he said during the roundtable discussion we attended at the start of the festival. “What we’re hopeful for is that while we put this together, there’ll be good learnings. We believe this is also a time of creating hope, a time of creating a positive view, because we do want to emerge out of this stronger.

“I think the media industry has a role to play to help tell the story of innovation, of creativity and how we’re all going to come out of this potentially stronger.”

Aside from Lau, the press con was also graced by SGIFF executive director Emily J. Hoe, SGIFF artistic director Kuo Ming-Jung, ATF group project director Yeow Hui Leng and SingTel’s Cindy Tan.

This year, we chose to focus on SGIFF’s short-film, 17-title slate because it featured four Filipino films, each of them as beguiling as the next.

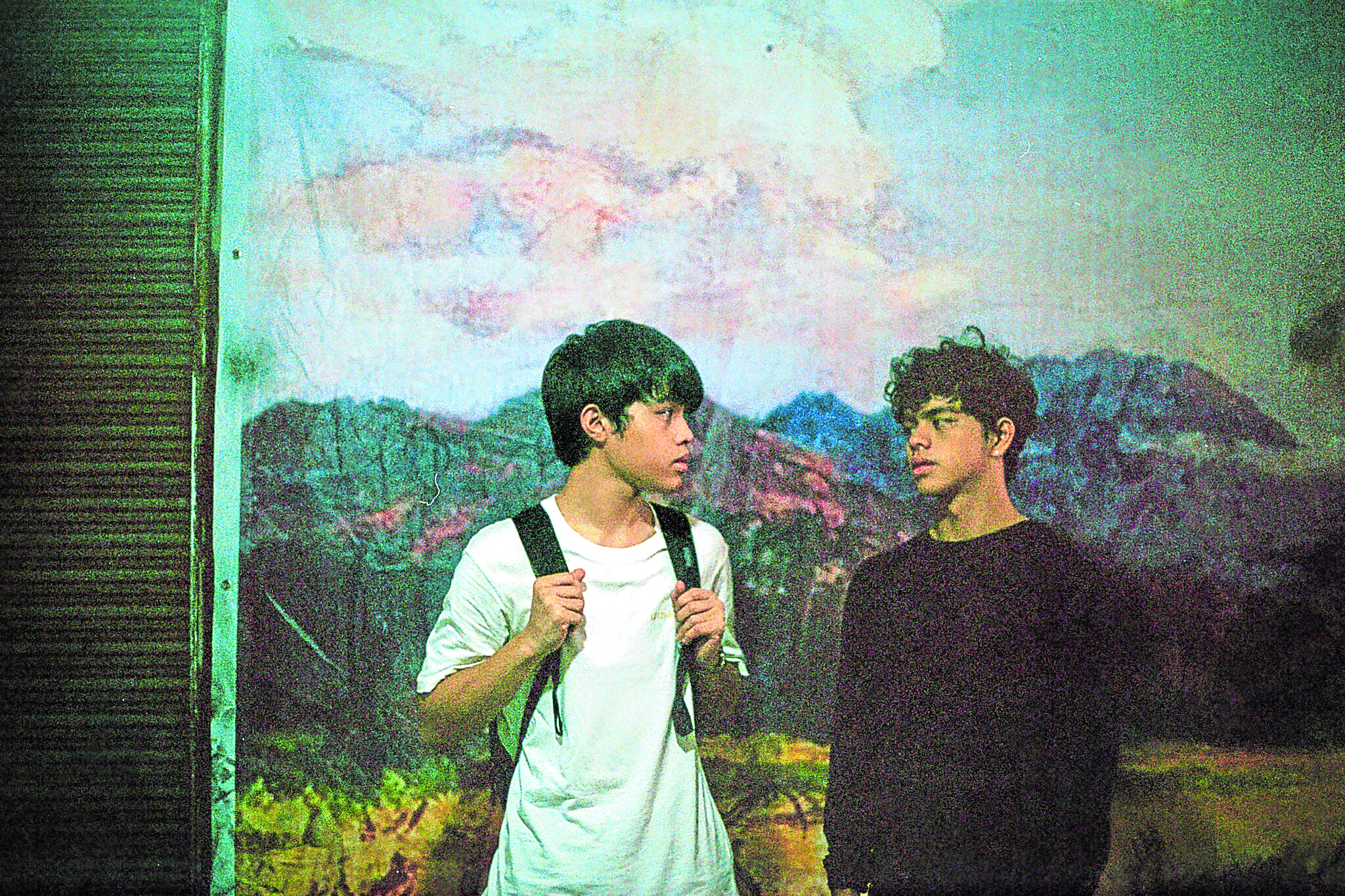

They are Rafael Manuel’s “Filipiñana,” a Silver Bear Jury Prize winner at the Berlin fest this year; Joanna Vasquez Arong’s Slamdance-winning docu short “To Calm the Pig Inside (Ang Pagpakalma sa Unos)”; Che Tagyamon’s QCinema winner “Judy Free” and Petersen Vargas’ provocative “How to Die Young in Manila,” made even more viewable by the presence of the popular “GameBoys” tandem of Elijah Canlas and Kokoy de Santos.

“Filipiñana” follows a day in the life of new “tee girl” Isabel (Jorybell Agoto) at a ritzy golf course as it tackles social hierarchy.

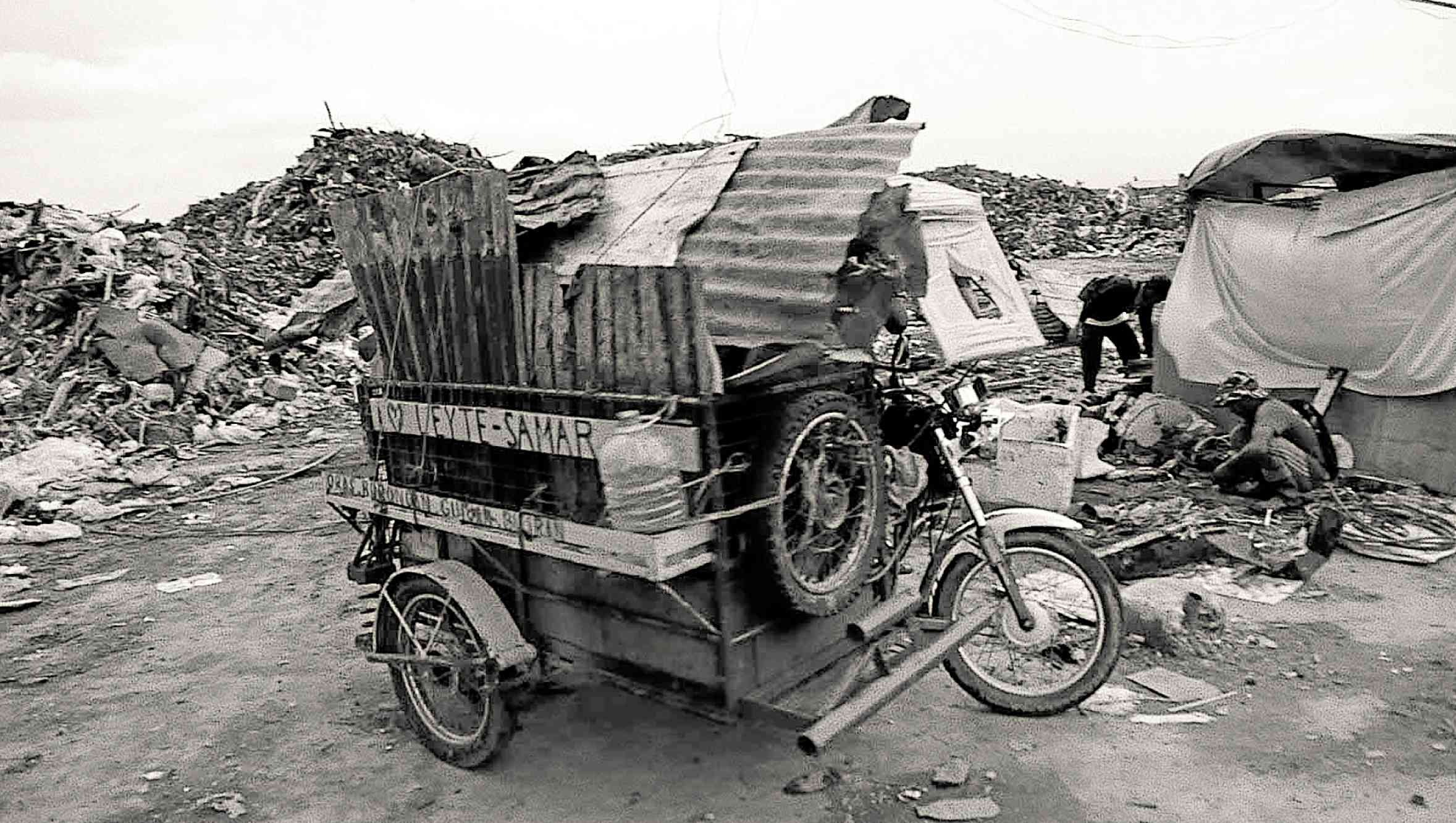

The mesmerizing and deeply contemplative “To Calm the Pig Inside” merges myths and devastating memories following the devastation Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan) had wrought upon a seaside city in the Visayas.

“Judy Free” is an impressionistic musing about how Pinoy migrant workers’ families (including Meryll Soriano and Miel Espinoza) are changed by many years of estrangement.

And the allegorical “How to Die Young in Manila” examines the wheeling-and-dealing that takes place between a sexually impulsive teenage boy (Elijah Canlas) and a group of street hustlers (led by Kokoy de Santos).

Despite their hectic schedule, we’ve managed to gather the fabulous foursome of Manuel, Arong, Tagyamon and Vargas (through his representatives) to discuss their films in this quick Q&A:

How did the story and concept come about and why choose the short-film format over feature-length for this story?

Rafael Manuel (RM): When developing ideas, I’m usually drawn to environments and milieux that I find a bit absurd. In the case of “Filipiñana,” it was a setting I was very familiar with as I have been playing golf since I was about 4 years old. I would spend practically every day in the country club that the film was shot in ’til I was about 21 or 22 and moved out of my parents’ home in Alabang.

When you grow up in the bubble of a gated-community like the one I did in Alabang, it’s very easy for your perspective of the world to be very skewed. It was only when I moved away from the bubble that I started thinking about how absurd it all was—specifically, I’m talking about the nuances of country club culture, of servant culture, of upper-middle-class Filipino culture.

In terms of choosing to tell my story via a short film rather than a feature-length, it was first a practical decision, as I was not able to raise the funds that I needed to do a feature-length to a standard that I was comfortable with.

The film was actually first written as a feature and I’m currently working on a full-length film based on the short in Paris at the Cinéfondation La Residence of the Festival de Cannes. But retrospectively, I’m glad that we ended up doing a short first, because the industry hasn’t found a way to properly monetize the short form yet, you’re afforded a lot more autonomy of expression in a short as a filmmaker. And this is of utmost importance to me—to be informed by a sense of internal autonomy before any external market pressure.

And also, in a way, doing the short helped us build a profile for the feature-length project with our success at this year’s Berlinale. So now, hopefully, there’s more of a chance that we’ll be able to make the feature-length film in the way that we want to make it.

Joanna Vasquez Arong (JVA): In 2013, I spent time volunteering in Bohol after the devastating earthquake took place just three weeks before Supertyphoon “Haiyan” wreaked havoc in the Philippines.

The politicking of aid during the earthquake was disheartening and, in fact, the group I volunteered with even had a huge banner on the side of their truck saying, “No to Politics.” We had never imagined that what happened in Bohol was only a taste of what was to take place in Tacloban, after the devastation of Haiyan.

After spending considerable time in Tacloban and Guiuan, where Haiyan first made landfall, and coming across so many different stories that people shared with me, I thought it would be interesting to do a feature-length film with three short stories from these three areas. So, we ended up creating two short narratives in Bohol, as well as in Guiuan.

For Tacloban, I knew the only way to relay the stories was through a documentary. I just had to decide what form of documentary to tell it. Eventually, I decided that the essay form would be the more powerful way of relaying the stories I heard.

The reason I had originally wanted all three shorts in one long film was to emphasize how there seemed to be a cycle recurring, regardless of which town we were in. For the longest time, we tried to make the feature film with all three shorts work, but it just didn’t click.

And on its own, with space and time to breathe, I feel “To Calm the Pig Inside” is now more powerful.

Che Tagyamon (CT): My sister and I used to draw doodles on our old photographs when I was a child, erasing our faces and other people on them. At one point, I thought that it would be interesting to use it as a tool to represent the absence and alienation I’ve felt from my own relatives who left the country to become migrant workers.

Petersen Vargas (PV): The idea came while preparing for the full-length film. First off, we wanted to show Petersen as an artist at this moment. What are his concerns and how he views the world, spiritually, philosophically and aesthetically. So, we embarked on the idea of this walking film with a specific atmosphere attuned to what is happening in our country today. That’s when we thought of images of dead bodies. From there, everything came together as a sort of mystery about danger, of the city and of desire.

(Conclusion tomorrow)