How Ben Wheatley’s ‘Rebecca’ veered away from Alfred Hitchcock’s 80-year-old screen classic

What a day my Thursday last week turned out to be. I just finished my interviews with the exciting lead actors of a much-anticipated London-set series when I got a call from Netflix asking if it was alright with me “to get in sooner” for my 1-on-1 interview with director Ben Wheatley.

By “sooner,” that meant exactly two hours earlier than my scheduled Zoom audio chat with the director of such film fest darlings as “Free Fire,” “Sightseers” and “A Field in England.”

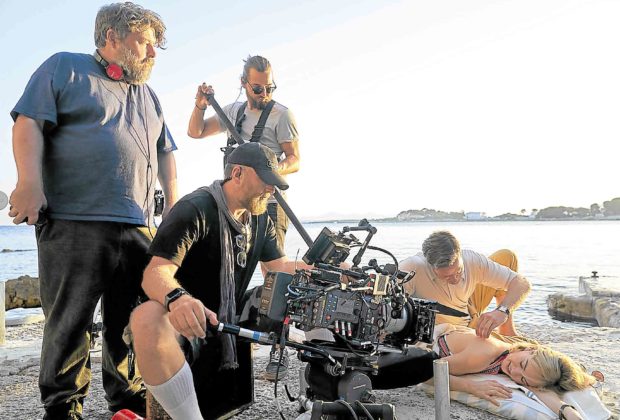

The 40-something filmmaker is also the man behind the latest screen adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel “Rebecca,” starring Armie Hammer, Lily James and Kristin Scott Thomas, which begins streaming on Netflix today.

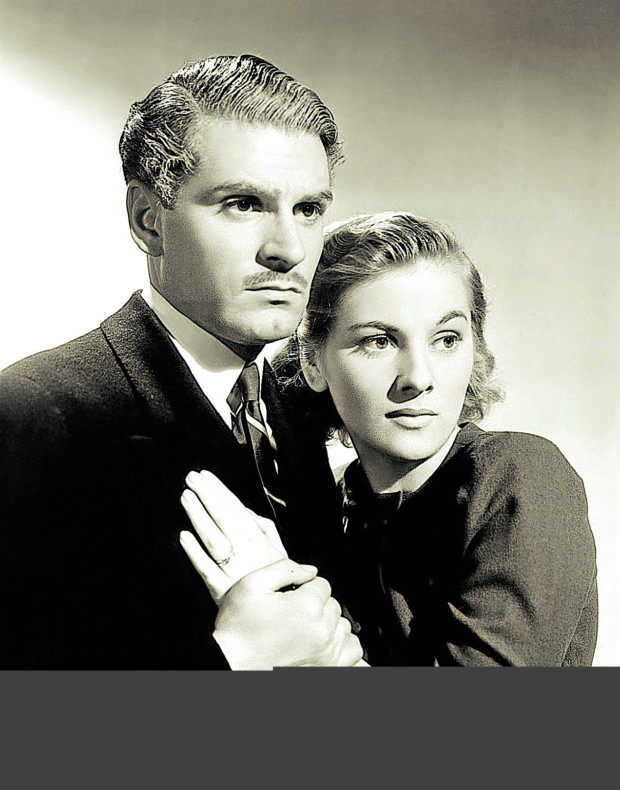

Full disclosure: I watched both films consecutively. But having sat through Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 version of “Rebecca,” starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine, then Ben Wheatley’s visually stunning 2020 iteration thereafter, you can imagine why I was more than eager to talk to Mr. Wheatley sooner. Our other option was to stay up until our 1:50 a.m. appointment with the British megman, so my answer in the affirmative was a no-brainer!

To my pleasant surprise, I ended up seeing the eloquent director sitting behind his desk at his lovely home office, which initially made me worry if I looked “presentable” enough at 12 midnight (it was 5 p.m. in the United Kingdom). I had limited time with Ben, but I needn’t have worried because Ben spoke “volumes”—one answer from him was worth three questions, at least.

Article continues after this advertisementAware that “Rebecca” was first adapted for the big screen 80 years ago, Ben knew he had big shoes to fill—after all, the 1940 version wasn’t just Hitchcock’s first film in the United States, it was also his first and only Oscar best picture winner.

Article continues after this advertisement“To me, it would have been more terrifying to treat the film as a remake of that classic more than as an adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s novel. There’s no way you could get anywhere near [Hitchcock’s version]—you’d just be completely crushed underneath it,” Ben said when we asked if he wasn’t daunted by the prospect of people comparing his movie to Hitchcock’s.

He added, “What attracted me to it was the idea of bringing the book to life. It’s interesting when you look at the book and you see the differences between the novel and the 1940 adaptation—because there were things that the latter couldn’t do that we were already able to do for the latest adaptation.

“They left out sections from the book, which had something to do with the Hays Code (the self-censorship code designed to regulate the ‘moral’ content of Hollywood’s feature films in that era). There were things that Maxim de Winter (played by Laurence Olivier then, and Armie Hammer now) would not be able to do—you can’t kill someone, or commit a crime and get away with it.

“It completely changed the structure of the story. But in [screenwriter] Jane Goldman’s new adaptation, that was the leap that drew me to it. Rebecca, the novel, is a blueprint for thriller cinema and novels—there are so many elements in it that kind of appear again and again, like the idea of Mrs. Danvers (Kristin Scott Thomas) as a character that seems to turn up in a lot of different movies in many ways, like [Nurse Ratched in] ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ and on and on.

“I also felt that the book served as a beginning … a genesis, of sort … for the tropes and structure of the thriller genre, in which the reader is made complicit to the murders. So, in the end, you watch it and go, ‘Oh yeah, they’ve gotten away with it and are really happy.’ Their success and love are built around the body of a murder. It really drags you over the coals.

“And part of the beauty of the book is in the way Daphne du Maurier wrote it … it’s almost like it’s a dead book … where she says, ‘Oh, I’ll write a novel that will stop people from reading romance novels forever.’

“It’s like you’re destroying the romance genre for good (laughs). So, whenever you read a romance novel going forward, you’ll never be able to get this story out of your head. It’s like you trick the audience in and warm them up with a holiday in France for the first 20 minutes by way of a most romantic experience on the beaches in Monte Carlo.

“Then, you slowly take them apart—until the characters find themselves in a completely different space! In the case of the second Mrs. De Winters (Lily James), the choices she had to make to get to where she is turns her from this innocent, lovely person into someone entirely different by the end of the film.”

“Rebecca” is a rom-com- channeling summer romance that quickly spirals downward after lonely widower Maxim du Maurier (Armie) takes his second wife (Lily James) to his palatial home in the south of England and introduces her to his dead first wife’s loyal confidant, Mrs. Danni Danvers (Kristin).

Our Q&A with Ben:

How was it directing Armie and Lily in roles that are just as iconic as the 1940 film and the novel in which your film is based?

It’s interesting because I’ve been watching Armie’s interviews about this—and, when asked about Olivier’s performance in the first film, Armie goes, “Oh I didn’t watch it (Hitchcock’s ‘Rebecca’). I didn’t want to know about Larry Olivier’s performance.”

But, you know, the reason why Armie was the right choice for the role had to do with [believability]—you have to be able to ‘sell’ this idea of the romance being depicted in the story. And Armie certainly looks like a man out of time, like he’s a 1940s matinee idol, physically.

You see him collapse and crumble throughout the movie, which is attributed to the structure of the film where as one character falls, the other rises—and that’s where Lily’s character comes in. Lily becomes bolder and stronger, while Armie crumbles and dissolves.

What I like about Lily as an actress, which is useful in this type of role, is her likability. You just root for her and want her to succeed. That makes the task quite tricky [for any actress]. She plays someone who’s weak, but not weak enough to pull herself together at some point. She can’t be too strong—otherwise, she’ll break the structure of the film.

What about Kristin? What we found immensely satisfying about her performance is her decision to go for some subtlety, making her portrayal of Danvers’ intentions not as obvious as the original (Judith Anderson). She makes the film’s themes of isolation and alienation ring loudly—and it’s perfect for the time we’re in right now.

Yeah, we needed someone powerful for that character because she has a very small amount of [screen] time to make a big impact. It’s crucial to have someone play that kind of complexity, sternness and intelligence.

At the same time, I wanted that character to be vulnerable, as well—conveying her frustrations while playing well to the sadness and loss of Rebecca. Kristin didn’t turn Danvers into a two-dimensional character villain. She’s just trying to protect the memory of a loved one.

What is the film’s main theme, and what scene was hardest to execute?

There are two things that are going on here—one of them is about privilege and how some people will just float through life and get away with murder, literally, because they’re rich and good-looking, while other people have to struggle to survive.

Then, there’s the idea of having multiple truths and how you sift through them as you consider different perspectives. For instance, the whole film is not just a memory, not even a flashback—it’s a memory of a dream. How much do you believe any of those characters? Are Maxim, Rebecca and Mrs. Danvers really saying the truth? So, that stretches backwards and forwards.

As for the hardest part of the film, it boils down to one scene—which would be the boathouse sequence, in which Maxim talks about what happened to Rebecca. The whole film rests on it. I was nervous going into that, and a lot of rehearsals have gone into it. The scene has been rewritten many times, then it took a long time to edit. It’s the same as the book—the whole novel rests on that scene. That was quite hard to execute and pull off. INQ