U2 thanks PH fans for ‘patience’in politically charged musical spectacle

The venue was right across a church, so he might as well say a prayer.

And so, at the penultimate stop of U2’s “The Joshua Tree” tour at the Philippine Arena on Wednesday, Bono, the frontman of the seminal Irish rock band, asked for an “epic night of rock and roll transcendence.”

Ask and you shall receive.

“Thank you for your patience … It took us four decades [to visit here], but we feel welcome. This is for sure going to be the best show we play here,” he told the thousands of eager fans who had to endure torturous traffic to witness U2’s first and long-anticipated concert in the country, which was mounted by MMI Live and presented by Smart Music Live.

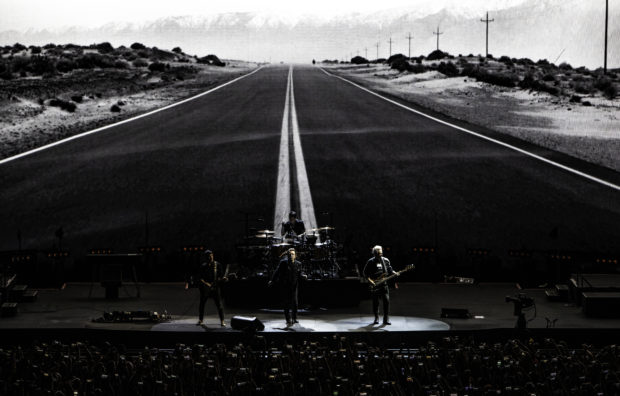

From the stage alone, it was apparent that this concert wasn’t any other show. The stage stretched 59 meters from left to right, coupled with a high-definition screen that was just as wide and stood 14 meters high. A protracted runway led to the B-stage that mirrored the silhouette of the Joshua tree centerpiece.

But as spectacularly enormous as the set was, it dwarfed Bono, guitarist The Edge, bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Muller only in size—for the sounds that emanated from their instruments and the messages their songs conveyed made all of them seem larger than life.

The sound quality and acoustics were top-notch, pounding and punchy without losing clarity even at thrashing volumes or the highest of frequencies. And it was all the better to appreciate U2’s roaring and anthemic instrumentation, particularly The Edge’s trademark guitar-playing, which

swirled like a maelstrom in “Gloria” and produced shimmery, jittery riffs in “In God’s Country”

Rising above the soundscape was, of course, Bono’s vocals, which remains forceful 2,050 shows into his music career. He let it rip in “Bad. “This desperation, dislocation/ Separation, condemnation/ revelation, in temptation/ isolation, desolation,” he bellowed.

In “With or Without You,” Bono played with dynamics, singing in hushed falsettos, then in pleading wails, as the slow-burning ballad built up to a crescendo.

As it all happened, the stage lights danced and the LED screen displayed immersive visuals that gave each number either a cinematic or trippy feel: Picturesque landscapes like the Zabriskie Pointe in “With or Without You,” neon rings in “Even Better than the Real Thing,” evocative vignettes of Native Americans in “One Tree Hill,” and a ravaged forest in “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For.”

In what turned out to be one of the night’s highlights, all such elements coalesced into a multisensory spectacle in “Where the Streets Have No Name.”

It began with the four men standing beneath the tree, as that unmistakable sound kicked in. With the first salvo of drums were a blinding blaze of stage lights. The LED screen sprang to life, showing a tracking shot of a desert road. And before everyone knew it, they were being engulfed by a tidal wave of sounds, visuals and emotions. “I want to run!” the packed crowd chorused.

Bono was a commanding presence onstage, whether simply walking about with his quiet, unhurried swagger, or putting on the theatrics. For most of the group’s 25-song set list, Bono managed to rouse the audience with a simple arm wave or a shake of a fist.

At times, all it took was the mere sight of him leaning into the mic, his right knee bouncing to the beat.

He can be quite the showman, too. Sporting an all-black ensemble, complete with a top hat and a sequin lapel jacket, Bono assumed the persona of “Shadow Man” in “Exit”—gesticulating and swinging around the mic stand, as he whispered lines from the novel “Wise Man” and the children’s counting rhyme, “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe.”

In “Mothers of the Disappeared,” a melancholic rock lamentation about women whose children were secretly abducted during the Argentine and Chilean dictatorships, Bono knelt down, took off his jacket, and sang before monochrome clips of women holding burning candles in the dead of night.

He also wore dramatic eye makeup in the latter half of the concert, which he then wiped off—ceremoniously so—before putting his sunglasses back on for “Every Breaking Wave.”

Bono, who’s also a known philanthropist and activist, has always used his music as a vehicle for his aspirations, advocacies and sociopolitical commentaries. Unlike most musicians who shy away from a making a stand on pertinent and controversial global issues because of potential backlash, Bono embraces it.

He wasn’t about to change that for this concert: He highlighted the importance of human rights every so often. He saluted activists, journalists and truth-tellers who “keep this country spiritually safe.” He championed female empowerment.

“Human rights churn out human wrongs, that’s a beautiful day. When sisters around the world go to school with their brothers, that’s a beautiful day. When journalists don’t have to worry about what they write, that’s a beautiful day. When women of the world unite to rewrite history as herstory, that’s beautiful day,” Bono said, after prompting a resounding sing-along with “Beautiful Day.”

The 59-year-old artist also touched on climate change. “This country is a miracle of a place … But we should be careful. Because with a blink of an eye, even the most beautiful landscapes can turn ugly if we don’t watch out,” he warned.

In “Ultraviolet (Light My Way),” meanwhile, Bono paid tribute to women from around the world who served as catalysts for nation building and social change, including Melchora Aquino, Corazon Aquino, Lidy Nacpin, Lea Salonga and Maria Ressa. The segment drew cheers. But there were also some booing—likely from those who don’t agree with the choices or share Bono’s politics.

Why did he have to mix entertainment and politics? Some of them wrote on social media later on. Never mind the fact that the album “Joshua Tree” is sociopolitically charged; that this tour was reportedly inspired, in part, by the 2016 US presidential elections; and that this show began with the marching beats and soaring melodies of “Sunday Bloody Sunday”—a song about the massacre of civil rights demonstrators by British soldiers in 1972 in Northern Ireland.

So, perhaps it was only fitting that U2 ended the night with arguably its biggest hit “One,” which—contrary to what its title suggests—isn’t exactly about oneness, Bono once pointed out, but living with each other’s differences. “We’re one, but we’re not the same,” the song goes. INQ