‘Balangiga’ bells ring again

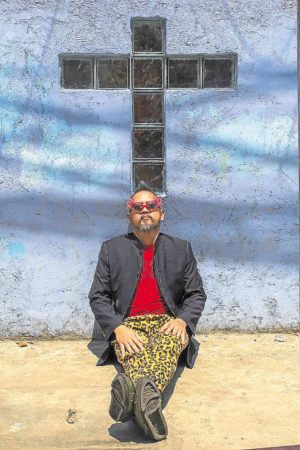

As he would often say: “Welcome to Disaster Filmmaking 101!” Against all odds, filmmaker Khavn dela Cruz finished his period movie “Balangiga: Howling Wilderness,” an entry in this year’s QCinema fest, ongoing until Oct. 28.

In a word, he described the 10-day shoot in Zambales as madugo. Indeed, it was “bloody.” Quite apt since it’s a movie that recounts the massacre of Filipinos at the hands of American soldiers in 1901. “I didn’t expect it to be that tough … it’s my 51st feature. I thought I knew it all by now. But, boy was I wrong.”

The biggest challenge was the “super uncooperative weather,” he recalled. “Unpredictable. We had to shoot rain or shine.” In extreme heat or drenched to the bones. “Everyone was getting sick. At one point, we were stranded on a mountaintop in the middle of a dark stormy night… Thanks to Typhoons ‘Isang,’ ‘Jolina’ and ‘Kiko.’”

Irony of ironies, the unruly weather “didn’t register on film.” “The deadly heat looked paradisiacal. The incessant rain looked like a mere friendly breeze.”

In the end, the climate became part of the picture, too. “The film is divided into three sections. The tempest occurred during the second part, which coincided with the flow of the story.”

As if it wasn’t arduous enough, he chose to shoot in “ravishing but harsh terrain. Botolan, Palauig and Cabangan.” He quipped: “The perfect footwear has yet to be invented. We got new wounds every day.”

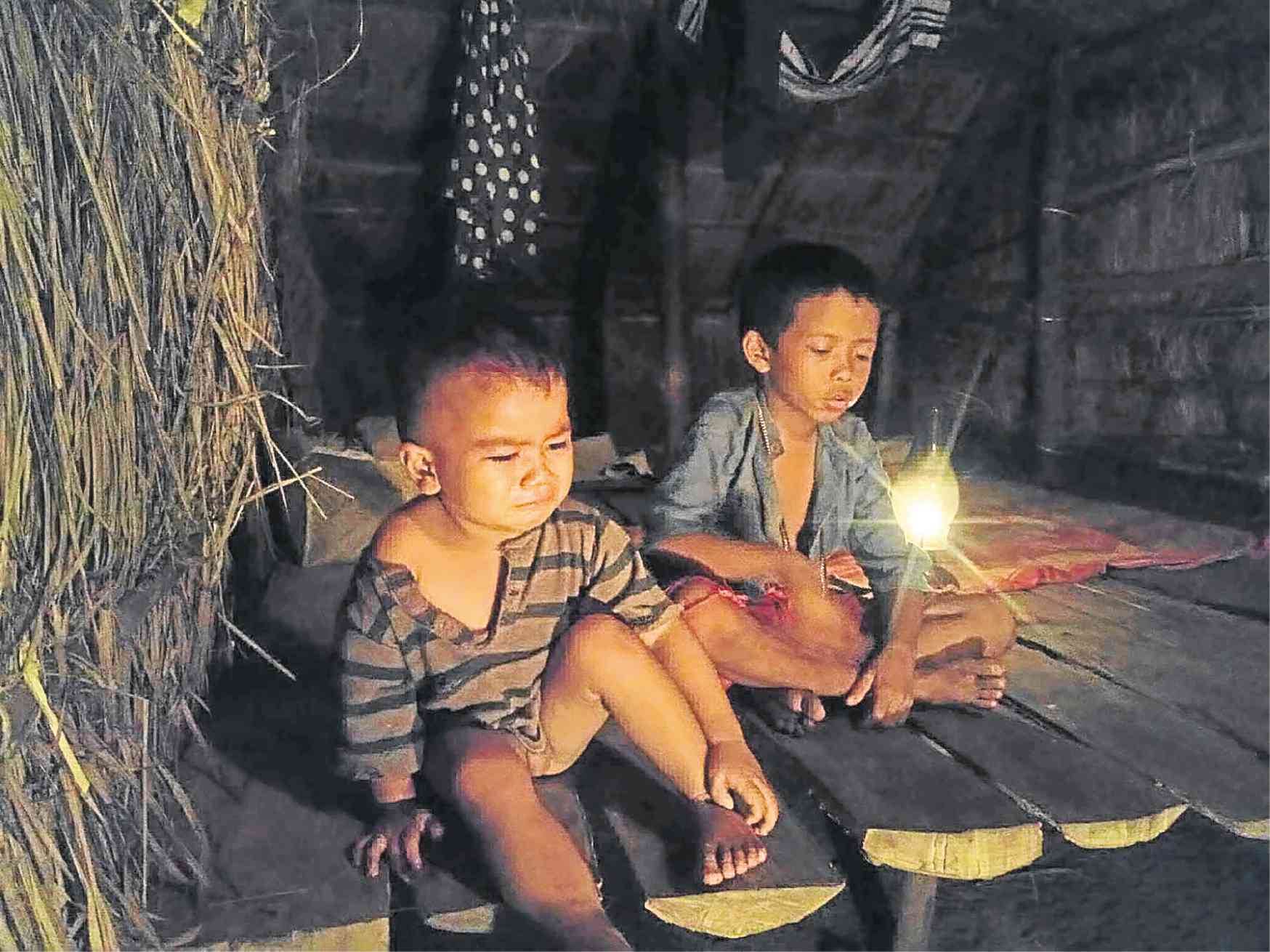

To top it off, he pushed himself further, by “directing the undirectables: animals and children.” Apart from 66-year-old Pio del Rio, the two other actors were 8-year-old Justine Samson and 1-year-old Warren Tuaño. Also, he threw a one-horned carabao named Melchora and a blue-and-gold chicken called Salvi into the melee.

As bonus, the film is in Waray. “A good translator is key. Shout out to Gianfranco Morciano!”

Needless to say, it confirmed a long-held belief. “Filmmaking is disaster management. You prepare as best as you can. But in the moment of truth, you simply had to plod on, like the carabao.”

His secret weapon? “What you lack in resources, you compensate with creativity. Hire a killer crew who won’t give up on the impossible dream of cinema … rely on new and old friends who will aid you in your hour of need”—which happens 24/7!

“Film is the youngest of the arts; its language, still evolving,” he explained. “In making a movie that’s more difficult than you can imagine, you are forced to go primitive, reinvent cinematic language more out of necessity than artistic vanity.”

Still, he feels strongly that this story should be told onscreen. “Because Balangiga happened, but the world has forgotten,” he asserted. The Philippine-American War has been kept “hush-hush for a long time.”

“Balangiga doesn’t exist in our textbooks,” he noted. “The bells, stuck as war booty in Wyoming and Korea, still haven’t been returned to the country. Filipinos still think all white men are Americans, and all Americans are saints.”

It is disheartening, he exclaimed, that the world knows about “Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and Korea, but not about the Philippines … not about Samar, not about Balangiga.” In a tragi-comic way, most historical accounts on Balangiga “focus on those poor Americans who were butchered by weird, cross-dressing pagans.”

In this light, his movie seeks to reclaim history: “This film zooms in on the Filipino story—one of the many Filipino families gravely affected by the atrocity. As Boy George [of Culture Club] sang: ‘War, war stupid!’”