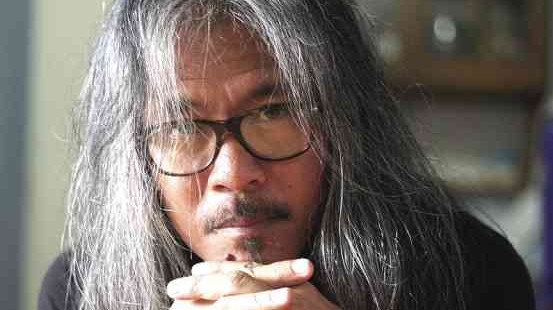

Filipino filmmaker Lav Diaz is flying to Berlin, Germany, to exhibit his 8-hour opus ‘A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery. INQUIRER FILE

Daring Filipino director Lav Diaz brings his movie house of pain to Berlin this week, shooting for the top prize with an eight-hour epic that tests human patience and endurance.

Diaz weaves the rich revolutionary history and mythology of his impoverished homeland in “A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery”, the longest film ever to compete at the Berlinale, but still three hours shorter than his longest work.

READ: PH team on the red carpet in Berlin | Piolo Pascual, John Lloyd Cruz are cool—Lav Diaz

“My principle is, the filmmaker shouldn’t struggle by himself…The viewer must struggle with me. Let’s experience this thing together and be immersed in this universe,” the 57-year-old Diaz told AFP in Manila before he left for Berlin.

Festival organisers have inserted one interval into the epic, but Diaz is relaxed about how audiences will cope.

“I understand the demands on the body, you need to defecate and urinate,” he says.

“You’re free. You can go home and fuck your wife or marry your girlfriend, you come back the film is still rolling. It’s about life. Ultimately, cinema is about life itself.”

“Lullaby” chronicles the futile search by Gregoria de Jesus — one of the few women leaders of the Philippine resistance against Spain — for the body of her husband, Andres Bonifacio, who was executed on a mountain by a rival faction of the rebellion.

Diaz weaves into the narrative the legend of the Filipino Hercules, who is perpetually holding the edges of two mountains to keep them from crashing into each other, and also the “Tikbalang”, a cigar-puffing monster with the head of a horse and the body of a man.

Another strand in the black and white movie is a retelling of “El Filibusterismo” a politically charged novel written during the Spanish period by the country’s national hero, Jose Rizal, to rouse nationalist spirit.

“I combined all these threads, and when you view the film, it is about the search for the Filipino soul,” Diaz said.

Soul cinema

Diaz has won numerous international and local awards. One of his most recent works, the four-hour-long “Norte, the End of History”, was screened at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.

This year, a seven-member jury headed by three-time Academy Award winner Meryl Streep will select the winner of the Golden Bear, Berlinale’s top honour.

But Diaz said he was not doing films to win awards or make money, but rather to help his countrymen find their national identity after centuries of colonisation by Spain and the United States, and more recently, a brutal dictatorship.

“Until now, we’re searching for that soul. I don’t want to make films for the market, I want to contribute to my country,” Diaz said.

Four metallic best picture trophies from the Filipino Critics’ Guild gather dust on his apartment shelf, beside a worn suitcase that has accompanied him on his many travels.

Diaz, admitted his movies were “so long nobody would buy them” but added: “I am freeing cinema. My films are not long, they are free. I am not part of convention anymore.”

He recalled a one-hour long scene in his 2006 film “Heremias”, where the entire shot followed three men getting high while they plot the rape of a woman.

“It was my vision of hell… It questioned God, if you really are God, why did you let these demons rape this beautiful woman?” he said.

Child of war

Diaz said his filmmaking perspective was greatly influenced by his tumultuous childhood, growing up in the conflict-wracked southern town of Datu Paglas.

His parents, both public school teachers, uprooted themselves from the peaceful north to teach children in war zones how to read and write. He fondly calls them “socialists”.

As a child in the 1960s, Diaz said he and his father would take a bus to the city to spend the entire weekend watching films by Fernando Poe Jnr, considered the Philippines’ John Wayne.

However, when their house was razed to the ground during crossfire between Muslim rebels and Christian militia groups, the family moved to a safe enclave while Diaz moved to Manila to study economics.

Diaz worked as a waiter, a book salesman and a petrol pump attendant after college to support his wife and three children, but eventually pursued cinema, his first love.

He started with low-budget skin flicks, including one about a woman who sleepwalks in the nude, before garnering critical acclaim.

“I am a film addict. I love all kinds of cinema,” he said.

While history and social injustice are running themes in his films, Diaz said the inspiration to start a project could strike anywhere.

A trip to the national library in 1997 spawned “Lullaby”, after he stumbled upon a decaying handwritten note from Gregoria de Jesus, describing her 30-day search in the mountains.

“I had an epiphany. I told myself: I have to make this film,” he said.

And the inspiration for his next opus could literally be just outside his window.

“You see that girl?” he said pointing to a beggar walking in front of a gleaming shopping mall.

“Why is she poor? Why does society allow her to be poor?”