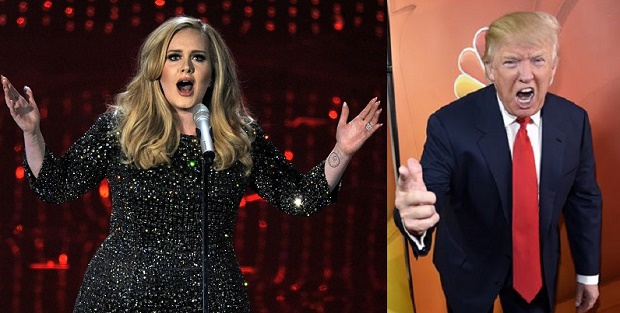

NEW YORK — While waiting for Donald Trump to take the stage this week at a campaign rally in Exeter, New Hampshire, fans listened to a few hit songs by Adele, “Skyfall” and “Rolling in the Deep.”

That has apparently hit all the wrong notes with the British superstar: She has said she’d like Trump to quit playing her songs at political rallies.

“Adele has not given permission for her music to be used for any political campaigning,” said Benny Tarantini, an Adele spokesman.

But mega-best-selling Adele may not be able to stop The Donald here.

Legally, the Republican presidential candidate has paid for the right to blast pretty much any music he wishes, as long as he does it correctly.

“Mr. Trump’s campaign paid for and obtained the legal right to use these recordings,” said Hope Hicks, a Trump spokeswoman.

Copyright experts say campaigns don’t need an artist’s permission to play their songs at rallies as long as the political organization or the venue has gotten what’s known as a blanket license from the performing rights organizations ASCAP and BMI.

The license isn’t for a single artist but for all the music in the licensing group’s repertoire, which is staggering. ASCAP represents over 10 million musical works from over 525,000 songwriters and composers. BMI represents 10.5 million musical works created by more than 700,000 songwriters. The license is for the right to perform the song publicly.

READ: Adele objects as Trump plays song

“When the campaign bus pulls into a town square in Iowa and starts blaring music, most times they’ve learned to get a license for that so they’re not violating a copyright,” said Lawrence Y. Iser, a partner and expert in copyright law at the Santa Monica, California-based firm Kinsella, Weitzman, Iser, Kump & Aldisert.

The campaign then must pay a small fee to the performing rights organizations. BMI, for example, charges 6 cents for every campaign rally attendee at an event where the music is played. A portion of the 6 cents goes to the artist.

But the use of the music can’t escalate much past the rally without more permissions. A political campaign, even with a blanket license, couldn’t use Adele’s music in a campaign commercial for TV or YouTube without permission and a separate license.

A long list of musicians, including Jackson Browne, Don Henley and David Byrne, have sued political campaigns for using copyrighted songs without permission in commercials or videos — but not for playing their music at rallies. Even so, artists have some recourse when it comes to blanket permission.

“We built into the license agreement a provision which allows a BMI songwriter or publisher to object to the use of their songs and, if so, we have the ability to exclude it from the license,” said Mike Steinberg, senior vice president for licensing at BMI.

That’s how Aerosmith frontman Steven Tyler last year got Trump to stop using the power ballad “Dream On” at campaign events. He sent a cease-and-desist letter to the Republican presidential candidate and BMI told the campaign that it would yank the tune. (Trump tweeted that he wouldn’t be playing the Aerosmith song anymore since he found a “better one to take its place.”)

Iser, who has represented Jackson Browne and Talking Heads frontman David Byrne when their songs were used in campaign ads, has been called in again this political cycle to represent songwriter Sean Altman in a dispute with the Rand Paul campaign over the use of Altman’s “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?” in a campaign ad.

Iser said the issue for artists isn’t about politics or how artists personally feel about candidates but about constitutional rights. “The Founding Fathers decided they get protection,” he said.

Iser also said there is a bigger legal argument to be made that campaigns that use songs also tap into the artists’ persona, voice and personality. “It becomes an endorsement,” he said. But so far, that argument is a gray area in the law. “Nobody has gone after a campaign for using a song at a live rally.”

Iser said one long-term solution to the fight over music played every election cycle would be to have ASCAP or BMI offer artists the chance to let them avoid having their music used at rallies entirely.

“It seems to me that there should be an opt-out ability where an artist — coming into an election cycle — who does not want BMI to license her music for any political campaign, should have that right,” he said.

Steinberg of BMI said that idea might be feasible down the road.

“It’s possible that may happen in the future. I think up until this point it’s been more reactive in terms of an after-the-fact questioning of the usage,” he said. “Perhaps it’s something that we might evaluate in the future as a way to avoid circumstances like this.”