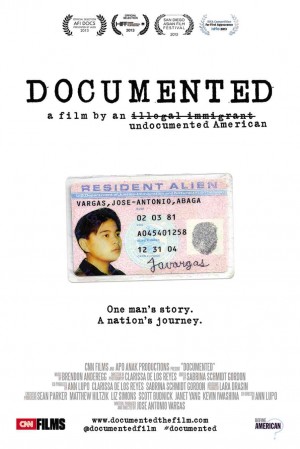

Filipino Pulitzer Prize winner Jose Antonio Vargas bats for legitimacy

LOS ANGELES—After breakfast last Monday morning—Cinco de Mayo—I sat down to watch Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas’ documentary, “Documented.”

JOSE attends a Mitt Romney presidential campaign rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in 2011. photo: Apo Anak Productions

Nothing prepared me for such a compelling, heart-wrenching experience so early in the morning. By coincidence, that day marked the 29th anniversary of my arrival in the United States as an immigrant.

Written and directed by Jose, “Documented” chronicles his journey as a 12-year-old who flew from the Philippines to the US to live with his lolo and lola (grandfather and grandmother); his discovery at 16 that his green card was fake; coming out as gay in high school, which prompted his lolo to kick him out of the house for several weeks; his internships at various newspapers that led to a job at the Washington Post (where he won a Pulitzer Prize as part of a team that wrote about the 2007 Virginia Tech University shooting massacre); outing himself again, this time as an undocumented immigrant in an unprecedented New York Times magazine essay; and his struggles as an immigration policy reform advocate and activist.

But what makes “Documented,” codirected by Ann Lupo, such a moving film is that Jose, as quoted in the production quotes, decided “to tell a more personal story and frame the issue as a familial one.” He elaborated, “Immigration, at its core, is about families. In my mind, I didn’t make a film about immigration. ‘Documented’ chronicles a story of love between a mother and a son.”

The immigration issue is fleshed out—in Jose and his mother Emelie, separated for more than two decades (a footage of them seeing each other and conversing for the first time in years via Skype is priceless); in his lola who still worries about Jose and dotes on him when he visits her in Mountain View, California; and in the “DREAMers,” undocumented youth who lobbied for the Dream Act immigration bill.

The film is universal and very Filipino at the same time. Actress, indie film producer and former model Bessie Badilla, who co-emceed events with Jose in New York, said she “cried the entire time” that she watched “Documented.”

Do see “Documented”—it’s a riveting, powerful film, whatever perspective you watch it from—whether as an immigrant, documented or undocumented, or simply as a human being. The documentary is now showing in NY, opens in LA today, May 9, at the Landmark Regent Theater in Westwood, then rolls out to other cities in California, Arizona, Washington, Florida, Colorado, Illinois and Washington, DC.

Below are excerpts from our e-mail interview with Jose:

What do you remember about flying to the US? You were only 12. How did the smugglers accomplish this? Who accompanied you?

I remember being on a plane for the first time. I had the window seat and my last memory of the Philippines was seeing so much water when I looked out. When I think of the Philippines, my childhood in Zambales, I think of the water.

I was introduced to a man who, I was told, was my uncle. In my family, everyone was an uncle, so I assumed that he was, indeed, my uncle. As it turned out, he was the smuggler paid to accompany me to the US. I don’t remember his name or his face.

The film shows several situations where you are overcome by emotion. How uncomfortable or challenging was it to be followed around by a camera? Were there instances when you asked the camera operators to stop?

It was very, very, very uncomfortable. I don’t like photos of myself, much less footage of myself. There are no photos of me in my apartment. The only mirror I have at home is in the bathroom. In short, I’m not what you would call “camera-friendly.”

But when the documentary took a much more personal turn, there was no running away from the camera. Film is very literal—it captures everything, simply and clearly. The camera is a good BS-detector; any trace of falsehood is easily caught and magnified. For those reasons, I found this project challenging.

I did ask the cameraman to stop, twice. The first time was when I learned that I did not qualify for the Obama administration’s deferred action program. I walked out of my apartment and asked the camera to not follow me. The second time was when I first watched my Mama’s footage from the Philippines. I was overwhelmed.

When you saw the finished film for the first time, which parts were difficult for you to watch?

The hardest to watch, during and after editing, were all the scenes with my Mama, especially our Skype conversation that she and I had. It was—it is—surreal to get to know my own mother through film. I was 12 when I left; too many years have passed and I’ve seen more of my mother (in film) in the last 18 months than I did in the past 20 years.

What has been your most hostile encounter since coming out as an undocumented American?

YOUNG Jose with his mother Emelie Salinas, years ago in the Philippines. photo: Apo Anak Productions

I get a lot of hate e-mail, some ignorant tweets and Facebook messages. But for the most part, I’ve found that anyone’s anger and/or hostility have much more to do with them than with me. In other words, people project their ignorance. They want someone to blame and they think that someone is me, the “illegal.”

The most hostile encounter was captured in film, in that Alabama scene (a drunk interrupted an interview that Jose was conducting and said, “Get the motherf***ers [undocumented immigrants] out of here”).

What do you miss most about your lolo? How painful was it that your coming out as gay was hard on him?

We had a close relationship when I was in middle school—before I found out that I was here illegally. (He learned that his green card was fake and confronted his grandfather, who admitted that he purchased the card). He worked the graveyard shift as a security guard and sometimes I accompanied him. We’d listen to old tapes of Tito, Vic and Joey while drinking Slurpee from the 24-hour 7-Eleven.

I miss his stories about growing up in Pangasinan and Zambales most of all. He told a lot of stories.

It was very difficult to come out to him about being gay. He was a devout Catholic and thought it was a sin, and his plan was for me to get married, to get my papers.

Lolo and I reconciled when I was older and more independent. I knew he was proud of me, and I’m sure he’d be proud of me now. Lolo’s favorite song was Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” That became one of the mantras of my life as well.

You were expected to grow up, get a “regular” job and lead a quiet life as an undocumented immigrant. Instead, you became a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. To what, or whom, do you attribute your success as a journalist?

No one—no one—succeeds alone. I owe whatever I have become not only to the family I was born into (my grandparents, uncles and aunts, my mother’s sacrifice), but also to the family of mentors and friends that I was fortunate enough to find.

Couldn’t any of the news organizations that you worked for gotten you a worker visa?

The immigration code is as complex, if not more so, than the tax code. It’s not easy for someone like me to get a worker visa because I came to the US using false papers. By the time I understood my legal predicament, I had claimed US citizenship in employment forms.

Have you considered applying for an O-1 visa, which applies to highly talented persons and can potentially lead to a green card?

Again, because I had admitted to claiming US citizenship and using false papers (doctored Social Security card, for example) when I applied for jobs at the San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post and Huffington Post, I am barred from any sort of relief. My lawyers and I are pursuing other means of adjusting my immigration status. Of course the solution, not only for me but for millions of others, is immigration reform.

How do you imagine or visualize the moment when you are reunited with your mom, if it happens?

I’ve imagined and fantasized about that moment for years. I’d rather it was just ours to share, she and I, no cameras, no witnesses. I fly into Manila, she’s waiting for me, we drive to Zambales—a long drive, during which she and I talk non-stop. Then we stop at one of those beaches that I loved while growing up in Iba.

That part in the film where your mom says she was hurt that you did not accept her Facebook friend request—a situation that parents all over the world can commiserate with—is sad and funny at the same time. Why did you hold out on that for several years? And what is it like now to have her as a Facebook friend? What are her comments on your posts?

Accepting her Facebook friend request meant opening up my whole life to her. I was not ready for that. She and I barely spoke on the phone; the cost of our physical and emotional separation was too high.

Now that we are Facebook friends, at least my online life is open to her. She doesn’t comment much. But we talk on the phone more regularly now.

If you are finally able to travel outside the US, which countries, aside from the Philippines, would be among your first destinations?

I would love to visit Prince Edward Island, Canada, where “Anne of Green Gables” was set. (He recounts in the documentary that he acquired an American accent by watching that film, other movies and TV shows). I would love to visit India—all parts of it. I’m fascinated by that culture. I would love to see Paris, Cape Town, Istanbul. I would love to see the world. I hope and pray that people who have valid passports do not take [that privilege] for granted.

What are the latest developments in the fight for immigration policy reform in the US?

We are at the mercy of a dysfunctional US Congress and waiting for leaders, especially in the Republican Party, to truly lead and get something done. There’s a lack of urgency in our politics to deal with something as urgent as this issue.

What if, indeed, the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service) suddenly turned up to deport you?

I am prepared for all possible consequences. I thought this through very carefully before “outing” myself as a TNT (acronym for the Filipino phrase “tago nang tago”—or constantly hiding), as undocumented, almost three years ago. I spent practically 14 years of my life, from age 16, being scared—of my government, of my family, even of myself. Fear no longer overwhelms me like it used to. The only thing I fear now is not having impact, and not seeing my Mama soon.

(E-mail the columnist at rvnepales_5585@yahoo.com. Follow him at https://twitter.com/nepalesruben.)