Passage to Tacloban

In Tacloban these days, the simplest conversations could assume a totally different meaning.

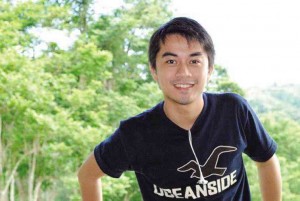

Trekking across his home province of Leyte two days after Supertyphoon “Yolanda” slammed into the country, young filmmaker Randolph Longjas observed that the question, “Okay kayo?” was being interpreted in various ways.

“Okay kayo?” he explained, usually meant, “Is everyone in your family accounted for?”

If the answer to that was “yes,” said Longjas, whose family survived intact, the conversation would then lead to “relief and genuine happiness.”

For many other Taclobanons, he said, the question could also mean, “Is your house still standing and can you now see the stars at night from your roofless home?”

Article continues after this advertisementSharing with others

Article continues after this advertisement

On various occasions, “Okay kayo?” has meant, “May na-loot ako, gusto n’yo? (I have looted goods; would you like some?)”

Friends, relatives, even total strangers did not think twice about sharing what little they had with others, Longjas said. “Someone we didn’t know gave us a can of fruit cocktail that served as our meal for the day.”

On the night of Nov. 9, Manila-based Longjas started his journey home to Tacloban to search for his family. It took him over 24 hours to reach the devastated city.

“The last time I heard from my mom was at 5 a.m. on Nov. 8, when the storm made landfall,” he recalled. “I didn’t hear from them for the next 24 hours. I was worried sick.”

Armed with several cell phones and battery packs borrowed from friends, a little cash (also borrowed), a few canned goods and a medical kit, he embarked on the life-changing trip.

One-day travel

“I traveled by air, sea, land and on foot in one day,” he recounted.

He took a commercial flight from Manila to Cebu, then a fast-craft boat to Ormoc, Leyte. “Since the Ormoc-Tacloban route was still impassable at the time, I traveled south to Baybay, where I took a habal-habal to Abuyog,” he said.

A habal-habal is a modified motorcycle with extended seats to accommodate five passengers, including the driver, he explained. “From Abuyog, I took another habal-habal to Tacloban.”

Most people were scurrying to get out of the province; Longjas was headed in the opposite direction. He recorded scenes from that surreal “exodus” with his cell phone camera.

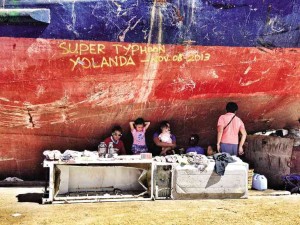

When he finally reached his home city on Nov. 11, he was shocked by the devastation. “This is not Tacloban anymore,” he told himself.

He related: “There was looting, chaos everywhere … everyone was on the road, walking. They were tulala (stunned). The destruction was so massive, I couldn’t find our house.”

When he finally did, the Longjas family home in San Jose (near the airport), the place where he grew up, was nearly unrecognizable.

“Yolanda destroyed everything,” he said. “Floodwaters had filled the house up to the ceiling. When it subsided, knee-high black mud covered the floor. We found an oxygen tank and a water tank in our front yard. Until now we don’t know where those came from. I am thankful that the walls of our house withstood the force of the deluge.”

All together now

His priority was to get his family out of the city. With the help of friends and coworkers, he managed to move his relatives to Manila.

“We are now living in my one-bedroom condo unit in Ortigas, all 18 of us—from my mom’s brothers and their families down to my cousin’s new baby (who was born a day after the storm). Okay lang kahit siksikan, ang importante buhay silang lahat. (The place is cramped but it’s okay; what’s important is that they’re all alive.) Little by little, we are able to talk about our experiences and joke about them.”

His father, Amancio, Tacloban Station 1 chief of police, stayed back “to fulfill his duty.”

At the height of the storm, Amancio was not at home, the young filmmaker said. “He was on duty at an evacuation center. My mother and siblings were prepared. They had water and food supplies. They even cut the mango tree in our yard. But they didn’t anticipate the storm surge.”

In a matter of minutes, he was told, the entire house was flooded. “My mom and adopted brother floated on a mattress. My youngest brother punched a hole in the ceiling so they could stay in the crawl space.”

Christmas as usual

Needless to say, Christmas will be different this year for the Longjas family. They hope to return to Tacloban for Noche Buena, though.

“Even if there’s no water or electricity, I’m excited to celebrate it there,” the filmmaker said. “Instead of Christmas lights, we’ll be more than happy to have candles. For sure, this will be a meaningful Christmas. For the first time in my life, I feel content. We may have nothing, but I feel like I have everything.”

It is bittersweet that Longjas’ debut film, “Ang Turkey Man ay Pabo Rin,” an entry in this year’s CineFilipino festival, finally opened in theaters last week— in Ayala cinemas nationwide, except in Tacloban.

“The catastrophe has made me look at things differently,” he said. Forget fame and fortune; his dream is to see Tacloban back on its feet. “I’d want to help my community, by distributing flashlights, radio units, watches, things that will allow them to reconnect with the rest of the world. Once electricity is restored, I hope to have a free screening of ‘Turkey’ in Tacloban—to provide my fellow Taclobanons a little entertainment and divert their attention away from their loss.”

Jump-starting life

He remains optimistic. Two weeks ago, he visited Tacloban. “There was a big improvement,” he reported. “People were starting to clean up their homes and communities. Several groups, including the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation, spearheaded a ‘cash-for-work’ program. Residents were paid P500 a day to clean their own communities. They cleared the roads.”

Activities such as these jump-start the local economy, Longjas noted. “Some residents have opened small sari-sari stores. Money is circulating. Taclobanons now see that they need not rely on relief goods.”

He has utmost faith that the Taclobanon spirit will shine through in this dark hour. “Ninety percent of the city was damaged; now is the perfect time to build the best Tacloban—a stronger city, with residential areas in the right locations, and with storm-surge barriers and effective drainage systems.”

Instead of getting dragged down by the politicians’ “tiresome” blame game he also noticed that most Taclobanons have decided to “do their own work, if on a smaller scale, focusing on their neighborhoods and families—although many are still in dire need of assistance.”

He said, “Yolanda completely altered the way we think, act and live.”

But certain things will remain unchanged—like his memories of his beloved city: “I was born and raised in Tacloban. As a kid, I would go to the beach every Sunday—enjoying fresh buko juice while watching the waves. I’ve always regarded the city as my comfort zone. What just happened made me realize that, no matter how busy or how far ahead you get in life, you will always keep coming home. It’s a reminder that it’s the simple things that make a person complete.”