A ‘Jingle’ film: The docu as creative repetition

“What is the point of revisiting the past?” a philosophy teacher once asked in class. “Because by doing so,” he said, “one inevitably discovers something new.” Some call this creative repetition or, in Filipino, “mapaglikhang pag-uulit.” A good example is “Jingle Lang ang Pahina,” a documentary.

“Jingle” was the name of the now-defunct music magazine founded by Gilbert Guillermo in 1970, which literally taught teenagers how to play the guitar—thanks to a diligent staff who took great pains in designing an all-in one guitar chords centerfold for each issue. Jingle also set its young readers off on a life-long record collecting adventure, on the strength of well-written album reviews that employed a rating scale ranging from the ethereal angel to the dreaded “bangaw.”

Between mastering power chords and dissecting album reviews, the readers often found themselves plotting baby steps towards “DJ-hood,” or starting their own band. Few of these would come to pass, of course, but the wide array of its articles sure had a way of making one dream of alternative realities. Lav Diaz, the acclaimed filmmaker who started out at Jingle, calls this “transcendence.”

Alternative realities

Most people very likely couldn’t care less that there was more to Jingle than the writing and spot-on guitar chords. This is where “Jingle Lang ang Pahina” comes in. Chuck Escasa’s documentary astutely positions the iconic magazine as a precursor to alternative publications that mushroomed after Ninoy Aquino’s assassination. The fact that it was launched at a time when Ferdinand Marcos was about to declare martial law may help explain this. Like almost everything at the time, it couldn’t escape the context of the First Quarter Storm. Interestingly, that context—essentially anti-imperialist and antifascist—aligned itself with the true north of rock music. Thus, in 1972, Jingle was among the publications shut down by Marcos.

“Jingle Lang ang Pahina” is a celebration of music journalism. Its writers worked in rented houses instead of posh offices. Their payback paled in comparison to what they’re probably enjoying today. But they enjoyed something their readers could only dream of: The opportunity to listen to, and review, the latest albums. And boy, did those reviews compel people to buy the albums! In the very least, they moved readers to fire off letters putting specific writers to task for not appreciating certain albums.

Not only did the writers listen and critique. According to Mike Jamir, one of the very first Jingle writers, they lived out their lives through the songs that they featured. That’s probably because the lyrics and chords that appeared in the centerfold flowed from endless hours of listening to the records. They even had a term for it: “sinipra.”

Guitars, guitarists

Jamir is only one of many writers featured here. The docu finally affixes faces to the by-lines—Juaniyo Arcellana, Pennie Azarcon-de la Cruz, Romy Buen, Emmelyn de Guzman, Manny Espinola, Jing Garcia, Tony Maghirang, Ces Rodriguez, Edwin Sallan and Dinky Aguilar.

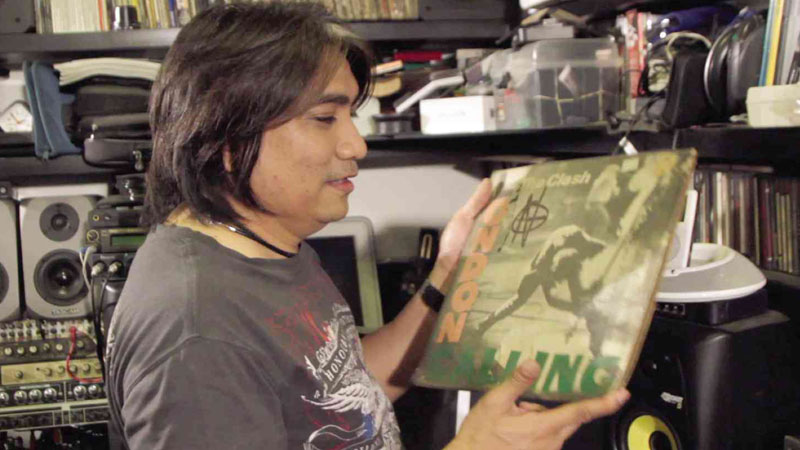

There is also something here for the collector of vinyl albums, a format given up for dead after the 1980s. The docu takes viewers to that era when Jingle writers competed in reviewing vinyl albums by the dozen.

Against a backdrop of thousands of vinyl albums and the iconic Technics SL 1200, Allen Mercado recounts how Jingle nurtured his record-collecting hobby.

There is no Jingle without guitars and guitarists. There are plenty of them here: The Juan de la Cruz Band waxing poetic with “Pagod sa Pahinga,” Chicoy Pura singing the blues with “Rage,” Gary Perez revisiting “Tao,” among others.

The idea of making a docu about Jingle gestated in Escasa’s mind for years. In 2012, he received a grant from the Film Development Council of the Philippines, along with his wife Aimee, who also received a grant to write, direct and edit a feature film titled “Asin.”

12-day shoot

The couple shot “Jingle Lang ang Pahina” for about 12 days between February and May last year, which should explain the title. Chuck wrote and directed the film; Aimee edited it. To be sure, they had their share of challenges, chief of which was scheduling the interviews. To maximize their budget, they squeezed in four to five interviews in one day. “Minsan ’yung mga available on a certain date, magkakalayo ng locations. One time, we started in Mandaluyong, proceeded to Makati, then Quezon City and finally, Parañaque. All in one day. Ako pa ang nag-drive,” said Chuck.

All the hard work paid off. The Young Critics Circle short-listed the docu—which premiered in FDCP’s First Sineng Pambansa in Davao last year—as one of 2012’s best indie films. It was nominated for best editing as well. Chuck is all praise for Aimee, whom he considers one of the best “cutters” in the country. “She has an incredible feel for timing and detail. She sifted through over 50 hours of footage and created a tight but free-form narrative,” he said. “I like its raw, fragmented structure. Parang Jingle.”

No comeback

Could this trigger the rebirth of Jingle Magazine for the 21st century? Eric Guillermo said this was farthest from his mind. After all, the Internet has superseded Jingle. So, if it is not about a comeback, what is the ultimate take-away from the movie?

The final musical segment could be instructive. “Betamax” by Sandwich may be an unabashed tribute to OPM icons. Its key message though, “Padayon, ipagpatuloy ang daloy ng alon” is not lost on the careful listener. To revisit the past, therefore, is to unearth something that would enable one to move forward. That is what creative repetition does. The philosophy teacher’s contention would be validated.