Why ‘Boses’ should be heard

Digital technology propelled this indie film’s journey to the cineplex, but it was fueled by pure passion, as demonstrated by filmmaker Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil and her friends.

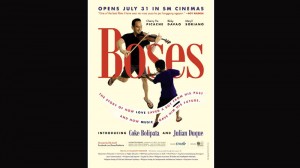

It has been five years since Marfil’s “Boses” debuted at the Cinemalaya; it finally opens in SM Cinemas on July 31.

Marfil admits that “Boses,” about an abused child and a troubled violinist who find redemption in music, can be a tough sell in a market teeming with romantic-comedies and superhero flicks.

“We first took the alternative route—screening in festivals, schools and communities, from New York to Tondo, from Yale to UP (University of the Philippines),” she recalls.

After a screening in a local school for boys late last year, a teenager convinced Marfil to try the commercial circuit.

Intense reaction

“The reaction to that screening was intense,” Marfil recounts. “On my way out, a student thanked me profusely. His voice breaking, he said, ‘Now, I know what I should do.’”

That encounter made Marfil realize that “Boses” had to “reach more people [via] the big screen, a powerful medium.”

Technology and serendipity pushed Marfil to take the plunge. In the same month that she met the grateful youngster, SM Cinemas went completely digital.

On a cold call, Marfil made a pitch to the mall giant. She relates, “Several executives viewed ‘Boses’ and, miraculously, said yes!”

Quixotic endeavor

A friend jested that Marfil seemed afflicted by jungle fever in her attempt to release “Boses” in commercial theaters. Perhaps it was a quixotic endeavor; to play safe, she fasted and prayed the novena. She jokes, “I do have prayer warriors, and I am on a lemonade diet.”

More than an advocacy film against child abuse, “Boses” is about young people finding their voice, the filmmaker stresses. “There are so many incidents of bullying among kids,” she points out, “so much violence in the streets.”

Marfil tapped a network of like-minded souls, until individuals and institutions vowed to help “Boses” find its audience. “It is this groundswell of support that emboldens me,” she says. “Art is a community endeavor. We hope people will consider themselves stakeholders in this project—especially teachers, whom I consider game-changers.”

Collaboration

It has been an “amazing and inspiring collaboration,” Marfil says. “The Department of Education and the Commission on Higher Education have released advisories on my film as a powerful advocacy tool for child protection. The Youth Commission of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines is endorsing ‘Boses’ for its child rights and family transformation values. Couples for Christ Taytay and Mandaluyong chapters are helping create buzz.”

World Vision Philippines, the Philippine Association of Gender and Development Advocates, Philippine Children’s Ministries Network, Ortigas Library Foundation, Ang Mananamplatayang Gumagawa Inc., among others, have also lent a hand.

Another motivation to go mainstream was lead star Julian Duque, a child prodigy whose gift as a violinist should be appreciated by a wider audience. Duque was 7 when the film was shot. He is now 12 and a scholar in a top school in Metro Manila.

The scholarship was made possible by his “Boses” costar, violinist Coke Bolipata.

Marfil says Duque is “thrilled” about the screenings. “He looks up to (costar) Ricky Davao (who played his abusive father) and hopes to become an actor of Ricky’s caliber someday.”