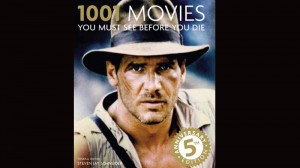

Thick tome enumerates must-see films

The massively thick compilation portentously titled, “1,000 Movies You Must See Before You Die,” provides good service not just to “ordinary” viewers, but to film buffs, as well. Most helpfully, it organizes its cinematic overview into decades, leading off with George Melies’ “A Trip to the Moon” (1902).

That first entry is instructively significant, because Melies’ film is unusually inventive, even if it was made at the very dawn of the new film medium! It just goes to show that cinematic creativity isn’t a matter of technology and big production budgets, but of individual artists’ visionary determination to tell stories their way.

Other early entries include movies that similarly added to the then still evolving Film Language. For instance, Edwin Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery” expanded the all-important possibilities of editing, as well as the pioneering use of the closeup. Ditto for D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of A Nation” and “Intolerance.”

Convoluted life

As for Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” it instructively employed “distortion” in terms of set design and camera angling to visually and insighfully depict its “dark” protagonist’s convoluted psychological life.

Also instructive is the fact that those early cinematic gems were created by visionary pioneers not just in the United States, but also in many other different countries, like France, Germany, Sweden (“Korkarlen”), Denmark (“Haxan”), and Russia (“Stachka”).

Film buffs and students should also take particular note of other classics like 1925’s “The Battleship Potemkin” by Sergei Eisenstein and Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis,” which took cinematic visualization and storytelling to a higher level.

Even in the field of comedy, notable contributions were made by movies like Charlie Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush” and Buster Keaton’s “The General”—which proves that you don’t need a weighty theme to make a major mark in cinema.

Alan Crosland’s “The Jazz Singer” pioneered in the use of sound and music in filmmaking. Even more experimentally, art films like Luis Buñuel’s “An Andalusian Dog” further pushed back the perceived “limits” to filmmaking.

Exclusive list

Asian filmmakers joined the exclusive list as early as 1937 with “Midnight Song” by Ma-ku Weibang, about a touring Chinese opera company. In Kenji Mizoguchi’s “Zangiku Monogatani,” a kabuki actor falls in love with his brother’s wet nurse.

In the ’40s, the standout films included the animated classic, “Fantasia,” John Ford’s gritty “The Grapes of Wrath,” Orson Welles’ over-arching achievement, “Citizen Kane,” Michael Curtis’ “Casablanca,” Marcel Carné’s “Les Enfants du Paradis,” David Lean’s “Great Expectations,” Frank Capra’s “It’s A Wonderful Life,” Chaplin’s “Monsieur Verdoux,” and Vittorio De Sica’s “The Bicycle Thief.”