From time to time, film buffs ask us to cite the best movie we’ve ever seen—but we quickly demur and say that we don’t go by that rigorous standard. We feel that it’s more helpful to recommend a number of excellent films, because each one has its own strengths or unique focus that the others don’t.

We arrived at this more “democratic” view of cinematic excellence in graduate school at Northwestern University, where our Film History professor opened our eyes to the many different possibilities and potentialities of the film medium by screening and discussing a wide range of productions from all over the filmmaking world, starting with some of the earliest movies ever made.

Those early movies were powerfully persuasive, because they showed film language itself in the very process of being created and invented, before our very eyes.

It was like we were entering into the minds of those pioneering movie directors, as they worked out basic problems like going from the long shot to the closeup, figuring out the advantages gained through more detailed editing, etc.

Artistic individuality

Most impressive of all, their early movies showed that enough money to spend was not the main factor involved in arriving at solutions to filmmaking problems—rather, it was the creativity and genius of the pioneering director or cameraman.

We also appreciated the importance of artistic individuality, of filmmakers doing something that nobody else had thought up or imagined. Thus, early on, we saw what made Luis Buñuel different from Yasujiro Ozu, Francois Truffaut, Sergei Eisenstein, Charlie Chaplin, Erich von Stroheim, Billy Wilder, etc!

For “evolving” film language, look for D.W. Griffith’s “Intolerance” and “The Birth of a Nation,” Edwin S. Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery,” Georges Melies’ “A Trip to the Moon,” Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” Robert J. Flaherty’s “Nanook of the North,” F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu,” Erich von Stroheim’s “Greed,” Sergei Eisenstein’s “The Battleship Potemkin,” Charlie Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush” and “City Lights,” and Luis Buñuel’s “Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog).”

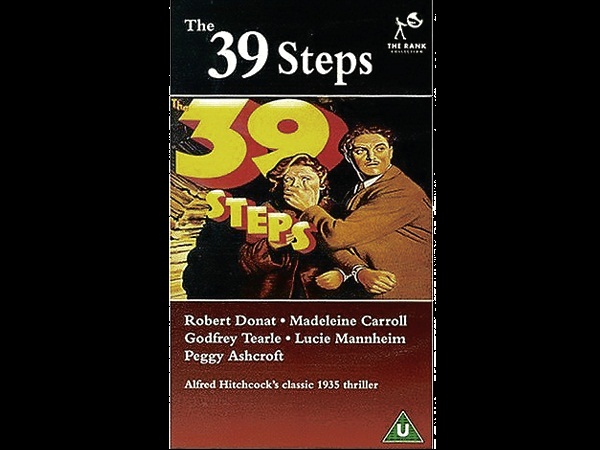

For individuality of cinematic vision and prodigiously expressive use of the new medium, look for Rene Clair’s “A Nous la Liberte,” Lewis Milestone’s “All Quiet on the Western Front,” Jean Vigo’s “Zero de Conduite” and “L’Atalante,” Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will,” Alfred Hitchcock’s “The 39 Steps,” Jean Renoir’s “La Grande Illusion,” John Ford’s “The Grapes of Wrath,” Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane”—and then some!

Sense of history

Film buffs and students who watch at least some of these seminal productions will develop a sense of history and context that will serve them well in years to come. These movies will