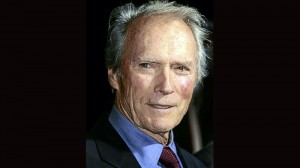

In his latest starrer, “Trouble with the Curve,” octogenarian screen icon, Clint Eastwood, plays another crusty old coot of a dysfunctional dad, and Amy Adams portrays his issues-encumbered daughter. Together, they make their characters’ conflicted relationship acutely believable.

The film’s resident father and daughter love each other, but they live apart. She had become a hotshot lawyer, but is forced to take an unexpected leave from her high-flying career when she learns from her dad’s friends that he’s losing his eyesight, among other physical infirmities.

Since he’s a baseball talent scout, he may be forced to retire—and that would really be the death of him!

Despite the obvious “dangers” involved, his worried daughter steps back into the risky minefield that their troubled relationship has become. She acts as his second and keener pair of eyes as he scouts for his team’s next big super-athlete-to-be.

The big fuss and bother is over an amazing batter. Instead of picking him, however, the scouting team discovers a heretofore unknown and unheralded pitcher.

But, the movie is really about how the estranged father and daughter can belatedly pick up the shards of their conflicted relationship, and make it whole again.

They wear their hurts and grudges glaringly on their sleeves, and have to humble themselves and admit to painful mistakes of the past to earn the right and “permission” to start afresh.

Adams does well as the aggrieved daughter, but Eastwood ends up “owning” the entire production, because of the bravely unflinching way that he lays his character’s heart and soul bare, for all to see, understand and learn from.

The actor who used to star in shallow “spaghetti westerns” like “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” has really come a long way—and doesn’t flinch at using the scars he’s “earned” to make his latest screen character powerfully real and “relatable” for viewers.

Yes, he’s played many old coots before, but this one is exceptionally choice and revelatory, because Eastwood’s portrayal is his most painfully “confessional” to date.

Just about the movie’s only flaw is the fact that it feels it has to add a melodramatic revelation toward the end of its “flashback” storytelling, to prove to the daughter that something he did when she was a child was not the act of rejection that she had wrongly interpreted it to be. The movie would have done just as well without that retroactive heart-tugger!