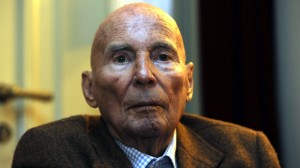

In this Sept. 11, 2012 file picture German composer Hans Werner Henze is photographed at the Saxony State opera in Dresden, Germany. German avant-garde composer Hans Werner Henze’s publisher says he has died at 86. Schott Music said that Henze died on Saturday Oct. 27, 2012 in Dresden. It didn’t disclose the cause of death. Henze’s work over the decades straddled musical genres. He composed stage works, symphonies, concertos, chamber works and a requiem. He once said that “many things wander from the concert hall to the stage and vice versa.” Henze was born July 1, 1926 in Guetersloh in western Germany. After studying and starting his career in Germany, he went to live in Italy in 1953. AP

FRANKFURT, Germany — Hans Werner Henze, one of Germany’s foremost composers, died at the age of 86, his publisher Schott Music announced on Saturday.

“With the death of Hans Werner Henze we have lost one of the most versatile, important and influential composers of our time,” Schott said in a statement on its website, saying the composer died in Dresden on Saturday.

Born in Guetersloh on July 1, 1926, Henze’s prolific output covered a wide range of works, including more than 40 operas and pieces for the stage, 10 symphonies, concertos, chamber music, oratorios and song.

“What is unique about his work is the union of timeless beauty with contemporary commitment,” Schott said.

Henze was openly gay and made his home in Italy, in the Albani hills outside Rome with his partner of more than five decades, Fausto Moroni, whom he met in 1964, but who died in 2007.

It was in the classical landscape of Italy “that he found his own harmonious balance of art and life — throwing himself into his many practical projects, entertaining generously with his companion Fausto Moroni, then retreating into his study and his scores,” the statement said.

Henze, perhaps best known for his symphonies and music theatre, enjoyed a unique collaboration with the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann, who wrote the libretti for his operas “The Prince of Homburg” (1958-59), “The Young Lord” (1964), “Elegy for Young Lovers” (1959-61)and “The Bassarids” (1964-65), which Schott described as “milestones in his compositional output.”

He was a prisoner of war in Fascist Germany and his experiences left their mark on his artistic output, notably in another stage work, “We come to the River” (1974-76) and in his ninth symphony written in 1995-97, which was based on Anna Seghers’ novel “The Seventh Cross”.

“With the unshakable courage of his convictions, but also with his joie de vivre, his love of beautiful things and of nature, Henze’s restless spirit reveals to us a man who never lost sight of his artistic aspirations, despite many personal sufferings, and historical dangers,” Schott wrote.

“To him, composing was both an ethical commitment and personal expression. He had to write, with relentless self-discipline, and when times were hard it threw him the anchor he needed and saved him from his darkest moments.”