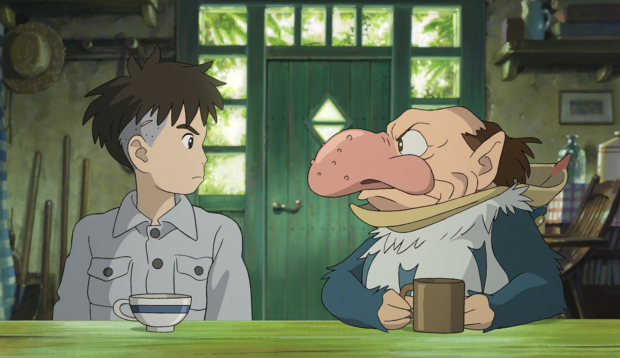

Mihato forms an unlikely partnership with a Grey Heron to save his stepmother Natsuko. Image: Encore Films and Studio Ghibli

Constructed near the headquarters of Studio Ghibli is a modest building that, as intended, functions as the “retirement office” of Hayao Miyazaki. To the surprise of no one, the building has failed to fulfill its essential purpose. For the third time in his remarkable career, the godfather of anime retracted his planned retirement to deliver his most personal film to date. With elements drawn from his childhood, “The Boy and the Heron” is a profound tale of acceptance and redemption amidst death and destruction. An instant modern classic, the film proves that the personal is indeed the most universal.

The classic Studio Ghibli film features a passionate child or adolescent surviving a fractured world. Fundamental to most, if not all, of these films, is the intense belief in the power of children to create a better future. “The Boy and the Heron” introduces us to Mahito, who is adjusting to a new life with his pregnant stepmother Natsuko, while processing the tragic death of his mother in a hospital fire. His life spiraled when he learned of Natsuko’s disappearance and realized his hope of finding her is an oddball heron. The feathered one revealed his stepmother is inside the obscure tower near their house—a creation of his enigmatic granduncle.

Death lingers throughout the film like the haunting original score of Joe Hisaishi. The film opens with a hospital fire that engulfed the mother. Shoichi, the father, is a merchant of death because he oversees an air-munition manufacturing plant. The idea of death is so pervasive I mistook a scene featuring workers transporting warplane canopies for a funeral procession. Based on previous Studio Ghibli experience, it is safe to assume the visual presentation (in this instance, the source of livelihood is also a tool for mass carnage) is deliberate because the esteemed filmmaker is unafraid of contradictions—life and death, creation and destruction.

Natsuko and her squad of grandmothers protect Mihato from the mysterious old tower. Image: Encore Films and Studio Ghibli

Festering underneath the charming traditional animation of Hayao Miyazaki is the inescapable brutalities of life. Or, in this particular film, the inescapable brutalities of his life. Like his latest protagonist, his mother spent a considerable time as a patient suffering from spinal tuberculosis, and his father supervised the manufacturing of warplane rudders. The eccentric granduncle, the creator of the tower and its numerous alternate worlds, could be a representation of himself or his professional relationship with Isao Takahata, the late animation titan and one of the three founders of Studio Ghibli.

The latter part of the film deals with the granduncle looking for a successor and mirrors the topic of succession that has long hounded Studio Ghibli. The passing of Takahata prompted his second failed retirement. Upon releasing his other personal film a decade ago, he announced his third unsuccessful retirement. We are fortunate that he is so bad at taking a hard-earned rest.

Toshio Suzuki, the third founding member of Studio Ghibli, disclosed that their latest film is their most expensive production ever. The list of voice actors includes some of the biggest names in Japanese entertainment, hired to breathe life into characters that around 60 animators worked on for about half a decade. While watching “The Boy and the Heron,” I realized it was my time watching a Studio Ghibli film on the big screen. I have seen all of their films and, as cliché as it sounds, there is something more magical seeing it inside a darkened hall with other people.