WASHINGTON – The first thing you notice when you see Marilyn Monroe’s full-length gloves in the storeroom of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History is how small her hands were.

“They’re one of a number of pairs she had,” says curator Dwight Bowers, gently lifting them out of the beige steel cabinet they share with Christopher Reeves’ Superman costume and the 10-gallon hat that J.R. wore in “Dallas.”

“They’re white kid. They’re very tiny and petite. And they show the decorousness of the 1950s,” he explained. “There’s a stain of ink on the left one … perhaps it came from giving an autograph to someone.”

Donated by a private collector, the gloves make up the entire Marilyn Monroe collection at the publicly-funded Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest network of museums and, in principle, repository of all things Americana.

Bowers, who plans to include the gloves in an forthcoming Smithsonian exhibition on American popular culture, said it’s “logical” for the museum to hold more Monroe memorabilia.

“But Hollywood material and Hollywood celebrities are big business in the auction world,” he told AFP in the windowless storeroom that’s packed floor to ceiling with show-business artifacts from vaudeville to today.

“Private collectors are part of our competition — and private collectors have a much bigger budget than we have.”

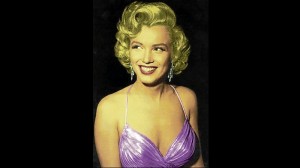

Fifty years after her death, demand for anything related to Hollywood’s original blonde bombshell — from the dresses she wore to the magazine covers she graced — is stronger than ever. And it’s more global as well.

Many choice items can be seen at the Hollywood Museum in Los Angeles, where a handful of private collectors have pooled their most prized Monroe objects for a summer-long public exhibition.

It’s a wide-ranging show, from the mortgage paperwork on Monroe’s house to never-before-seen photographs and a host of garments like the black silk crepe dress she wore on her honeymoon with baseball legend Joe DiMaggio.

“It had been in storage for 35 years,” Hollywood Museum founder Donelle Dadigan said. “When we received it, you knew who it belonged to, because the Chanel Number Five perfume still lingered… It was almost magical.”

The bulk of Monroe’s personal belongings went on the auction block at Christie’s in New York in October 1999 at a historic two-day estate sale that raked in $13.4 million.

“They literally had everything from pots and pans to her brassieres,” recalled Clark Kidder, a collector of Monroe-related magazines in Wisconsin and author of a 2001 guide to Monroe memorabilia who attended the sale.

The most expensive item then was a diamond-studded platinum eternity band, a gift from DiMaggio, her second husband, that Christie’s experts had estimated at $50,000 tops. It sold for $772,000 and it’s likely worth much more today.

Monroe’s baby grand piano went, too, for $662,500, along with everything else from a pair of bikinis and a set of gym equipment to her driver’s license — as well as the gloves that eventually wound up in the Smithsonian.

Such prices today would be considered bargains, due in part to the globalization of the memorabilia market and an influx of cash-rich and reclusive Asian and Gulf collectors for whom price is no object.

“Some of the top prices for Marilyn Monroe memorabilia, in the seven figures, you may end up finding in China, in Japan, in the Middle East … it’s just extraordinary,” Dadigan told AFP in a telephone interview.

Last year, in Macau, Los Angeles auctioneers Julien’s sold a gown that Monroe wore in the movie “River of No Return” for $516,600 and a signed nude from her “red velvet” session with photographer Tom Kelly for $16,250.

Earlier in 2011, the billowing dress that Monroe wore over that famously breezy subway grating in “The Seven-Year Itch” sold for a staggering $4.6 million — plus commission — in Los Angeles.

The seller was the actress Debbie Reynolds, who at 79 had no more room for her collection of 35,000 Hollywood movie costumes. The buyer, as is so often the case at auctions, opted for discretion and bid by telephone.

“A lot of these high-profile pieces, when they come up for auction, are going to the Asian countries,” Los Angeles collector Scott Fortner, whose own Monroe objects are part of the Hollywood Museum exhibition, told AFP.

“I find it disappointing that some of these pieces literally just disappear and we have no idea where they go,” added Fortner, who has catalogued his entire collection — from a feather boa to make-up and eye drops — online.

Fortner sees himself not so much as a collector than as a custodian of the memory of a timeless motion picture icon. He’s especially proud of one item in his possession — Monroe’s humble Brownie snapshot camera.

“I have always found that piece very, very intriguing,” he said. “It’s the childhood camera of one of the most photographed women, if not the most photographed woman, in the world. There’s an interesting bit of irony there.”