Actress Dexter Doria takes on ‘meaningful’ role as real-life foe of fake news

MANILA, Philippines — The veteran actress Dexter Doria is surprised by the success of her online program “DidiSerye” — a play on the popular reference to supporters of President Rodrigo Duterte — that debuted on Jan. 10.

Meant to promote fact-checking and debunk fake news, the series of vlogs has gathered thousands of fans this early on YouTube (almost 8,000 subscribers), Facebook (38,000 likes) and Twitter (more than 5,600 followers).

Each episode runs for about three minutes (“Better to keep it short than ramble on and on,” Doria says) and discusses pervasive misconceptions on social media. “Hindi paninira ang magsabi ng totoo” (Telling the truth is not putting down others) is the program’s slogan.

The latest installment of “DidiSerye,” for example, explains the improbability of the 192,000 tons of “Tallano gold” purportedly owned by the Marcos family and supposedly to be distributed to all Filipinos should Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the son of the late dictator, win the presidency in the May elections.

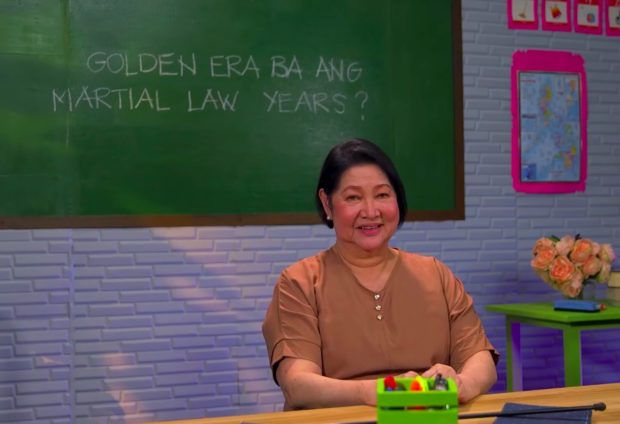

In the episode before that, Doria dressed as schoolmarm “Nana Didi” presented economic figures detailing the Philippines’ foreign debt, inflation rates, and the evils of crony capitalism to puncture the myth that martial law made up the country’s “golden era.”

Article continues after this advertisementDoria insists that she is not against a specific presidential candidate. “The vlog is mainly against fake news; it does not display any political leanings … It’s a shame that we have developed social media only to use it to spread fake news. We are wasting the gift of technology,” she says in a phone interview.

Article continues after this advertisementFalse narratives

For some time now, both scholars and ordinary observers have been discussing the prevalence of false narratives on social media, specifically about the Marcos family, that appear to bolster Marcos Jr.’s candidacy.

First-time voter David Gutierrez, 23, of Parañaque City admits to being dazzled by the Tallano tale, telling the Inquirer that he tends to believe it “because there are pictures on YouTube proving that the gold exists.”

Gutierrez says that after seeing the video, he is confident that Marcos Jr. will use the so-called gold “to help Filipinos, spend it on the poor … and to beautify (“pagpapaganda”) the Philippines.”

Danilo Rala Asilo, a 70-year-old community leader in Barangay BF Homes who has participated in local campaigns, takes the Tallano yarn one step further.

He cites a supposed YouTube video claiming that Marcos Jr.’s mother, Imelda Marcos, offered the gold stash to Congress in 1998, to be appropriated for projects that would benefit Filipinos.

Per Asilo, the story goes that the “dilawan” (opposition) lawmakers in Congress refused the former first lady’s offer because it would seem like the dictator did well (“lilitaw na magaling at maganda ang ginawa ni Marcos”) and his stock would be boosted (“aangat si Marcos”).

Asilo admits that he gets all his news from YouTube nowadays. “I hardly read newspapers anymore. There are no more deliveries because of the pandemic,” he says.

‘Hypnotized’

Doria agrees with the observation that the reduced circulation of newspapers has made people more dependent on social media. But she says its exploitation as a vehicle of fake news must be stopped.

“We want to promote fact-checking. People nowadays are so beholden to social media, they are hypnotized by it. As I said in the episode called ‘Confirmation Bias,’ there are those who will only talk to others who hold the same beliefs. There is no effort to fact-check. We do this to discourage fake news,” she says in Filipino.

“We” refers to the ragtag production team behind Doria’s three-minute videos. Composed of close friends and their spouses and children, these volunteers research the data, write the script and assist in setting up her shoot.

In one gathering where they enjoyed “red wine and nice cheese,” Doria says, the team acknowledged the need to clarify stories being spread in aid of historical revisionism.

“Wala man lang ba tayong gagawin? Why don’t we do something?” she recalls the team saying.

Doria, who recently won two best supporting actress awards for her performance as a mother struggling with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in “Memories of Forgetting,” was initially skeptical about doing a vlog. She wanted to know: Who holds the camera? Who takes care of the lights?

She does not go into specifics, only saying that some team members are skilled IT experts: “Magagaling sila, but they would rather remain incognito.”

How it was

Being vocal about her political opinions is not new to Doria. She was on her last semester in a humanities course at the University of the Philippines Diliman when the First Quarter Storm broke out in January 1970.

She recalls how it was then: “I was not active in the rallies but I knew what was happening. While I was not that militant, my younger brother was involved in [the activist group] Kabataang Makabayan and my father, [the late] Romy Taccad, was a former newspaperman who later worked behind the scenes in politics. He worked for Speaker [Cornelio] Villareal and Manila Mayor [Antonio] Villegas, so the talk at home touched a lot on politics and current events.”

Doria got married in February 1970 but completed her college course eventually. She took odd jobs after school — “Patalbog-talbog lang ako, not serious about anything” — even contributing articles to the weekly political magazine Graphic and Sunday Times Variety, until movie director Emmanuel “Maning” Borlaza noticed her doing a bit role in “College Girls.”

In 1977, she starred in “Tisoy” with Christopher de Leon and went on to do character roles that she finds more challenging.

“Nobody asked for my political opinions as an actress,” she says. “But during martial law, I was friends with people who knew things that were happening in government. People know I have opinions about the country’s leaders but I never went out publicly because nobody was interested [in asking me]. I was at Edsa with my friends in 1986.”

The way Doria remembers it, Filipinos were mostly clueless about martial law when Ferdinand Marcos signed the declaration in September 1972.

“What we were told was all propaganda. But what was happening behind that was a different story. That’s why we cannot allow martial law to happen again, or for another president to declare it. People trekked to Edsa to put it down,” she says.

Something meaningful

Doria admits to initially worrying about being bashed or getting threats to her security for doing “DidiSerye.”

She is thankful that feedback from netizens is mostly positive. “If ever there are negative comments, those who post positive ones defend me. I also noticed that those who follow are of different political persuasions. I think we attracted attention by posting a first episode about martial law,” she says.

“But I just want to do something meaningful in my life,” she adds. “I have about 10 to 20 years left in my life, probably. And as an actress, even less. I want a chance to do something against fake news.”