Pinoy Boys’ Love: A rising phenomenon in time of COVID-19 explained

“Gameboys The Movie” Japanese poster

As a BL (boys’ love) fan myself, I feel excited because, in a way, the series will be going back to its roots,” said Perci Intalan, one of the producers of Ivan Andrew Payawal’s well-loved series “Gameboys.”

Intalan recently announced that the movie version of the BL franchise that stars Kokoy de Santos and Elijah Canlas will be shown in Japan on Jan. 21.

“They noticed that ‘Gameboys’ received a rousing reaction from people here, so they got curious. They inquired about the possibility of distributing Season 1 there. I’m also happy because they’ve invested in the movie version as well as on Season 2,” said Intalan of the Japanese creators who partnered with main producer The IdeaFirst Company.

“We have three partners there—one for international distribution, another for theatrical release, and one for home video release. They said all inquiries about ‘Gameboys’ in Japan were very positive,” Intalan beamed. “They are very proud to say that BL came from them, especially since most people here think that it originated in Thailand.”

Yes, Intalan is correct. The genre, which features erotic and romantic relationships between boys or young men, originated in Japan in the 1970s.

Article continues after this advertisementA subgenre of shōjo

According to a report by Filipino professor and author Michael Kho Lim, BL was once a subgenre of shōjo (literally, “young woman”) manga, with contents mainly about romantic affairs between heterosexual couples.

Article continues after this advertisementLim is currently a lecturer at the School of Culture and Creative Arts, University of Glasgow in Scotland. He is also the assistant secretary of the National Committee on Cinema, a subcommission of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts in the Philippines.

Lim said that, over time, stories on homosexual and homoerotic relationships emerged as a result of the overly contrived and trite heterosexual love stories in shōjo manga. The subgenres called shōnen’ai (boys’ love) or bishōnen (beautiful boy) were then created.

Fast-forward to the 1990s, the popularity of boys’ love manga has spread to different countries via online fan communities. The label has since caught on as a generic term and was shortened to BL.

The phenomenon arrived in Thailand in the 1990s and gradually changed the Thai media landscape, as it proved that same-sex romance content can actually be a commercial success, Lim pointed out.

In the Philippines, it was not clear when the phenomenon started. However, Lim said it could have begun around the same time when “Love Sick: The Series” was released in 2016. In fact, the earliest recorded fan meet was with “Love Sick” main actor Vachiravit Paisarnkulwong (also known by his nickname August) on Dec. 17, 2016, at an event titled “August in Manila.”

Lim added that it was only in 2020 that Thai BL shows gained a considerably strong attention from Filipino audience.

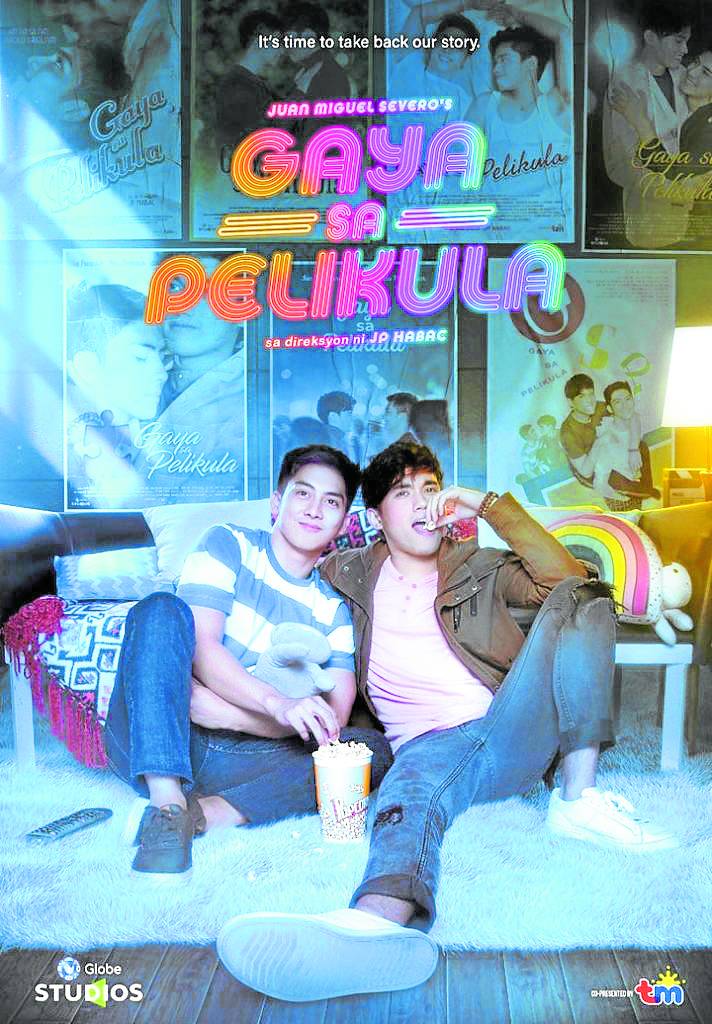

“Gaya sa Pelikula”

A good thing

For Dr. Ver Reyes, who is a licensed psychologist and psychometrician, the sudden increase in BL consumption is actually a good thing.

“It’s like we’re trying to normalize, as far as the entertainment industry is concerned, love stories about members of the LGBT community, and of the sexual or gender minorities. It’s a good step, a positive thing,” pointed out Reyes, who is also chair of the Psychological Association of the Philippines’ Teaching Psychology Special Interest Group.

As to why BL films and series have become popular of late, particularly during the pandemic and during the strictest implementation of the lockdown in 2020, Reyes has several observations.

“First, I feel that it has become popular because there’s a market for it here. Producing BL films or series doesn’t come cheap, but since you have a market, people will keep coming up with these type of products,” she explained.

“Second is that, people have more time to access them since everybody is doing their work and school at home and online,” said Reyes, who then shared the results of a recent study conducted by the group of Dr. Regina Hechanova-Alampay from Ateneo de Manila University to drive her point.

“They did a study on mental health because they wanted to create a program to help both faculty and students become more resilient during this pandemic,” she began. The team sought 800 respondents/participants for the survey and then did an analysis.

“The result was that the most vulnerable in relation to mental health concerns would be the younger generation (18 to 24 years old). The study also revealed that those with more concerns, in general, struggled with anxiety. It also showed that distraction is a coping mechanism in relation to resilience, well-being, anxiety and depression,” she explained.

Distracting activities

Reyes said her observation was that people would usually engage in activities that would distract them. “One way is by actually watching shows. It helped that people were given access to some of these BL series online—not all of these can be seen on free TV,” she pointed out. “I just have a disclaimer, though. The study is contextual. In other words, people will not automatically use distraction to cope. In fact, the research also looked into religion or spirituality, and this also positively related with well-being.”

Reyes also attempted to discuss what could be an “evolution” of the Filipino viewers’ taste and preferences. “We can say that people are becoming more tolerant, or accepting, or intrigued, to say the least, of what is really happening. Could it be that people have now accepted that gay actors are not only meant to do slapstick comedy?

“I may be biased because I’m a transwoman, but if you look at these love stories, they actually show other layers of intersections. For example, there are many normative stressors like traffic or the summer heat. We’re all affected by this, regardless of gender,” she began.

“There also came a time in our lives when we asked, ‘Does my crush also have a crush on me?’ This is normal for a lot of straight men and women, but for those who are members of the sexual minorities (lesbians, gays and bisexuals) and gender minorities (transwomen, transmen), there are more layers to this,” Reyes pointed out. “This is no longer merely about love. If one talks about love, or about his crush, will his family be ready to accept him? This is on top of the stigma that members of the LGBT are experiencing in general. This is one good thing that BL stories are trying to make us see.”

Reyes said that because of the BL genre, the misconception about same-sex relationship being merely about the desires of the flesh is slowly being erased. “This shows that they are people experiencing the same kilig moments, or the same apprehensions about their love not being reciprocated. At the same time, this also shows that these are the realities that LGBT people go through,” she stressed.

Tackling the topic in “a cultural studies perspective,” Lim likened what was happening to the BL genre to what he termed as the “Andoks phenomenon.”

He explained: “This means that when this particular brand introduced lechong manok to the market, everyone scampered to make their own version of the dish. That’s the mentality of Filipinos. We patronize something because it’s popular. This is pretty common in our culture.”

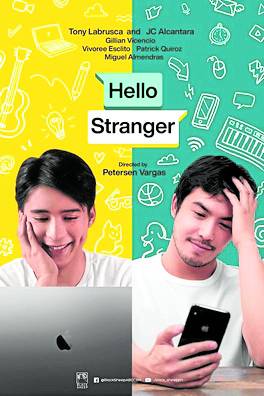

“Hello Stranger”

3 successful BL projects

For Lim, the three most successful BL projects are “Gameboys,” Petersen Vargas’ “Hello Stranger,” and Juan Miguel Severo’s “Gaya sa Pelikula.”

“These days, ang dami na, kung anu-ano na lang. I feel that the BL craze has reached its peak and will fade out soon enough. The market has become saturated that it’s now a matter of who comes up with the best storyline,” Lim observed. “Because there are so many of the same kind, some would merely resort to using ‘skin shots’ and a lot of kissing scenes. That’s what happened in the 1990s, when Filipino filmmakers began making gay films using digital cameras. It’s the same pattern all over again, only in a different form.”

“Back then, digital filmmaking has just been introduced. Everyone tried to make their own gay content. Eventually, this also died down,” he said. “I actually stopped monitoring the number of BL products already. My last count was 31, in August 2020. Now, I’m guessing that there are about 50 BL products, or more.”

Lim further said: “I read a study that stated that Thailand is already considered a BL factory. This is similar to our Star Cinema, which eventually mastered the art of creating rom-com (romantic comedy) films. It keeps on churning out the same kind of films. It would just change some of the elements.”

Reyes agreed by saying: “If you offer the same thing again and again, viewership automatically goes down. This is why our BL stories should not be the typical ones. I sometimes ask, ‘How come I don’t see any trans being featured in BL films?’ Or, ‘Why are the characters mostly teenagers? How come we don’t come up with stories that talk about professions, for example?’”

“This has to be tackled as well: What are the stereotypes? They would say, ‘OK lang na bakla ka, basta matalino ka,’ or ‘OK lang na bakla ka, basta maayos ang itsura mo.’ This also creates division within the LGBT community. If we want BL to be an ongoing discussion and push this in terms of advocacy, then these are the things we can consider,” she said.

Discourse on safe sex

Another topic that Reyes thinks is important in relation to BL is the discourse on safe sex. “It’s a good opportunity to explain to people that, yes, these interactions are happening between two people, but how do we protect ourselves and stay healthy? We feel happy and are entertained because of the kilig moments we see on screen, but we might be neglecting the fact that this has implications in the future.”

Reyes, however, pointed out that this does not have to be the main topic, but can merely be a theme or subtheme. “This is also one of the struggles of a lot of LGBT people. To whom can they ask questions? It doesn’t help that there are a lot of misconceptions as to how they can get AIDS/HIV (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus) or STD (sexually transmitted disease). Aside from exploring yourselves, your identities and knowing who you love, it is also important to take care of yourself. I think that should be the bottom line.”

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.