Brillante Ma Mendoza

Being a Filipino is something I’m proud of. That a great percentage of our people remains poor—no. For poverty is neither romantic nor exotic; it is a cruel thing, and this pandemic accentuates the disparity between the members of society—the affluent and powerful, the middle class, and those who struggle to get by each day.

In the history of developing nations, there were instances when fences were built to hide the poor from foreigners, especially those whose business is related to poverty alleviation. There were outcries because of this, with many insisting that a country must not hide the truth, however painful it may be. In the Philippines, the statistics on the citizens’ quality of life may vary depending on the region and the standard used to gauge it, but there’s no denying that many live below the poverty line.

In art and filmmaking, there’s the term “poverty porn”—which means an artist is exploiting the poor to gain attention and profit from it. I myself was branded as someone who creates poverty porn, because there’s a misconception that when you make a film, set in rough areas, and where characters are shown struggling, it’s poverty porn.

Great difference

That’s quite a modern term, but I think our past great artists’ older films that centered on stories of hardships did not suffer this type of branding.

There is a great difference between telling the story of the poor and dwelling on squalor—being out of touch, making the poor appear only as helpless victims of fate who do nothing but wallow in misfortune as they await charity.

Sometimes, we, filmmakers and critics included, forget that while we yearn to show the world prettier pictures of ourselves, we aren’t what people call a first-world country. Regarding vaccines alone, we’re with the rest of the poorer nations waiting to receive them. Even with mismanagement and other issues we complain about, they’re part of being a developing nation.

I remember an occasion in Europe when a Filipina asked me why I show poverty and despair in the lives of Filipinos in my films, and not focus on the beautiful aspects of the country. She said she had been working hard in that country, perhaps not just to earn but to also help erase that downbeat image of Filipinos in the minds of foreigners.

I understood her, but with a heavy heart, I had to tell her that her being there—instead of being with her family, being an employee and never the boss—proves my point: She left the country because there’s poverty and less opportunity for her in the Philippines. There are things we must do to live.

We are proud of our overseas Filipino workers, the modern-day heroes who sacrifice so much to seek prosperity abroad. Yes, we don’t wish to be perceived as underlings, but the bitter truth is that many of us have to leave our families to work as such in order to improve their lives.

If we were a highly developed nation, our people would not be so regularly deported for being illegals; Filipino mothers need not let go of their children’s hands at the airport and risk coming home in a box.

When my team creates films, we don’t glorify poverty—we dignify the efforts of those who contend against limits. We place the emphasis on their humanity. Poverty does not lessen a mother’s love; being poor and uneducated does not mean you’re weak, blind or dumb; knowing misery does not mean you’ll inflict pain on others; and being poor does not make one evil, though it may force him to commit evil.

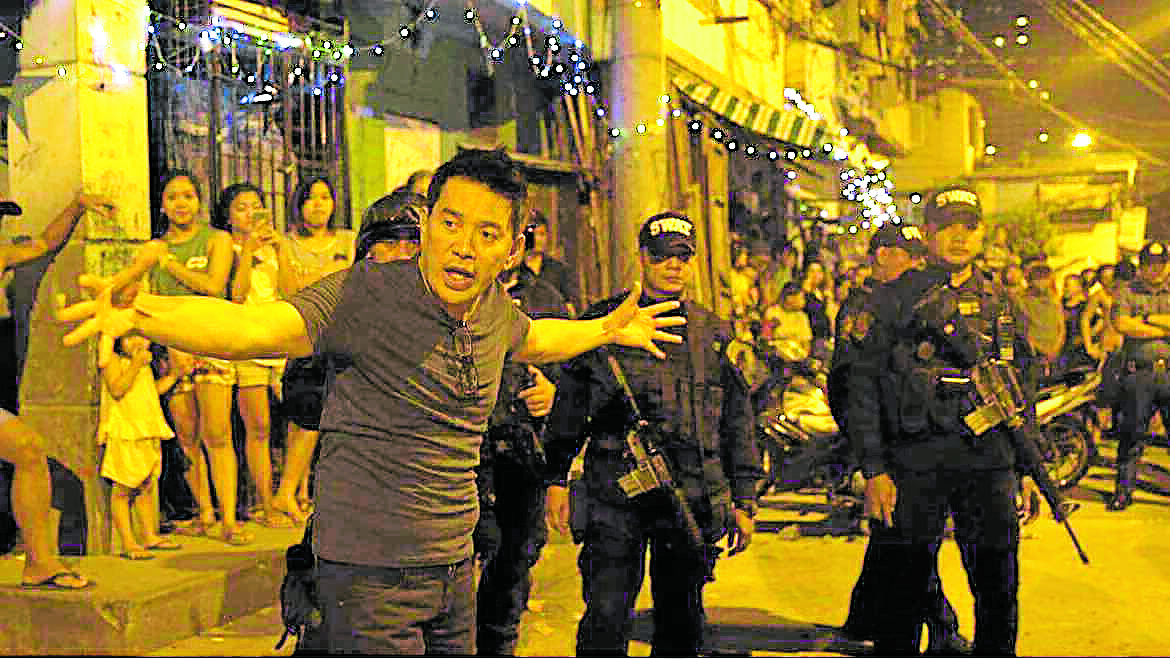

The author on the set of one of his films

Facades of decency

Let’s face it, between a poor man and a wealthy one, many will first suspect the former of a crime. The rich can perhaps afford better facades of decency.

Both the wealthy and the poor have stories. The setting may be different, but their paths will intersect. Some abuse those below them; some sacrifice to uplift their fellowmen. Some forgive, others take revenge. Some refuse to break, while others allow themselves to be devoured by their weakness. What unites us with the rest of the world? The human connection.

A Russian viewer told me that when he watched our film “Lola,” while he could not pinpoint what it was exactly, he nevertheless felt a strong connection with the Filipinos through the story, the characters of our grandmothers.

I understand there are claims that showing the unadorned truth will tarnish the Philippine image—but what many critics don’t realize is that, often, the audience does not think the way they do. Imagining themselves in our shoes, they feel for Filipinos who strive to overcome misery. Why are we so afraid of the truth destroying our image? Do we prefer to be loved and accepted for half-truths?

Truth: “Lola” was a film we made for a purpose that wasn’t 100-percent pure. Yes, we meant well—it was a beautiful story, after all—an honest tribute to grandmothers who occupy a special place in our hearts.

But sometimes, in our enthusiasm, we get carried away and don’t pause to examine that part of us, however miniscule, that isn’t genuine. An acquaintance suggested that we make the film so it can enter the Venice Film Festival. They can relate to it because there’s an area in Malabon that is flooded like some parts of Venice.

Remembering his words later, I realized that this is close to making poverty porn: To use Malabon’s floods, which its residents are forced to live with, to attract the festival’s attention. The film was successful in many ways, but I don’t forget that guilt.

Target market

Certainly, some artists focus on the stories of the rich, or members of the middle class who can afford to loll in breathtaking shores to nurse their broken hearts—because those are their target market.

I am simply an artist who chose to create more films about those who are often unheard and unnoticed, for I know my purpose. When we know what we’re doing, being branded positively or negatively should not preoccupy us too much. Opinions differ, and the topics we tackle are a matter of choice. But at the end of the day, a creator must be responsible for his own work and nobody else.

Putting on a blindfold

I’ve once mentioned the issue of Filipinos not watching art films. We hope to change this in time, but that’s another reality we must accept. My team is aware that, right now, most viewers of the films we create are those who have the means and the interest to do so—the stakeholders.

True, the malevolent will find ways to exploit and slight us, but also remember that elsewhere, a viewer will be moved to make a difference in the Philippines. We aren’t just waiting for saviors; we must first help ourselves. But we cannot fix our issues if we’re ashamed to look them in the eye. To me, fine human qualities like bravery and selflessness shine brighter in the darkest of places. Noble things have emerged out of the most humble homes. These are stories worth showing to the world. Let us elevate those who suffer, but let’s not fear showing our scars as a nation, because they’re part of our growth.

If, 50 years from now, we find that the majority of our people still live in sad conditions, that the injustices attached to being poor remain, it would be like an admission that many of us had contributed to the making of nationwide poverty porn. We all hope for an era when poverty will only be in films, a story we tell our grandchildren about. But right now, such is the reality for most of us in this nation, that we cannot build fences around so others will not see. There’s enough darkness now, and putting on a blindfold cannot help us move forward.