‘Photo Ark’: Race-against-time mission captures endangered creatures in all their majestic glory

You won’t save what you don’t love. That, in essence, is the principle driving National Geographic photographer and conservationist Joel Sartore’s 25-year mission to take a portrait of every endangered creature in the world—about 15,000 of them—before they go extinct.

The Photo Ark, an “advocacy of biblical proportions,” began to take shape 15 years ago in Joel’s hometown in Lincoln, Nebraska, and has since taken the seasoned 58-year-old photographer to 60 countries around the world in his Noah-channeling quest to create an archive of global diversity.

Joel’s project was first documented early this year in NatGeo’s “Photo Ark: Rarest Creatures.” The two-part series captured some of Joel’s close encounters with the first 5,000 endangered creatures featured in the Photo Ark—no easy feat for a photographic endeavor that requires its subjects to stay still or hold its best pose till the camera clicks.

Season 1 of the docu saw the globe-trotting photographer hopscotching from one exotic corner of the world to another—like Madagascar (for the high-jumping lemurs called Decken’s sifaka), New Zealand (the Rovi kiwi birds) and Czech Republic (for the fast-vanishing breed of northern white rhinos, of which only four are left). Along the way, Joel sought to identify the factors driving their extinction.

In the two-episode second season of “Photo Ark,” which premieres on National Geographic Wild on Wednesday next week, viewers will see Joel going to places like Manaus in Brazil, the Niwot Ridge in Colorado, Borneo and Bali in Indonesia, and a riverine forest in Des Moines, Iowa.

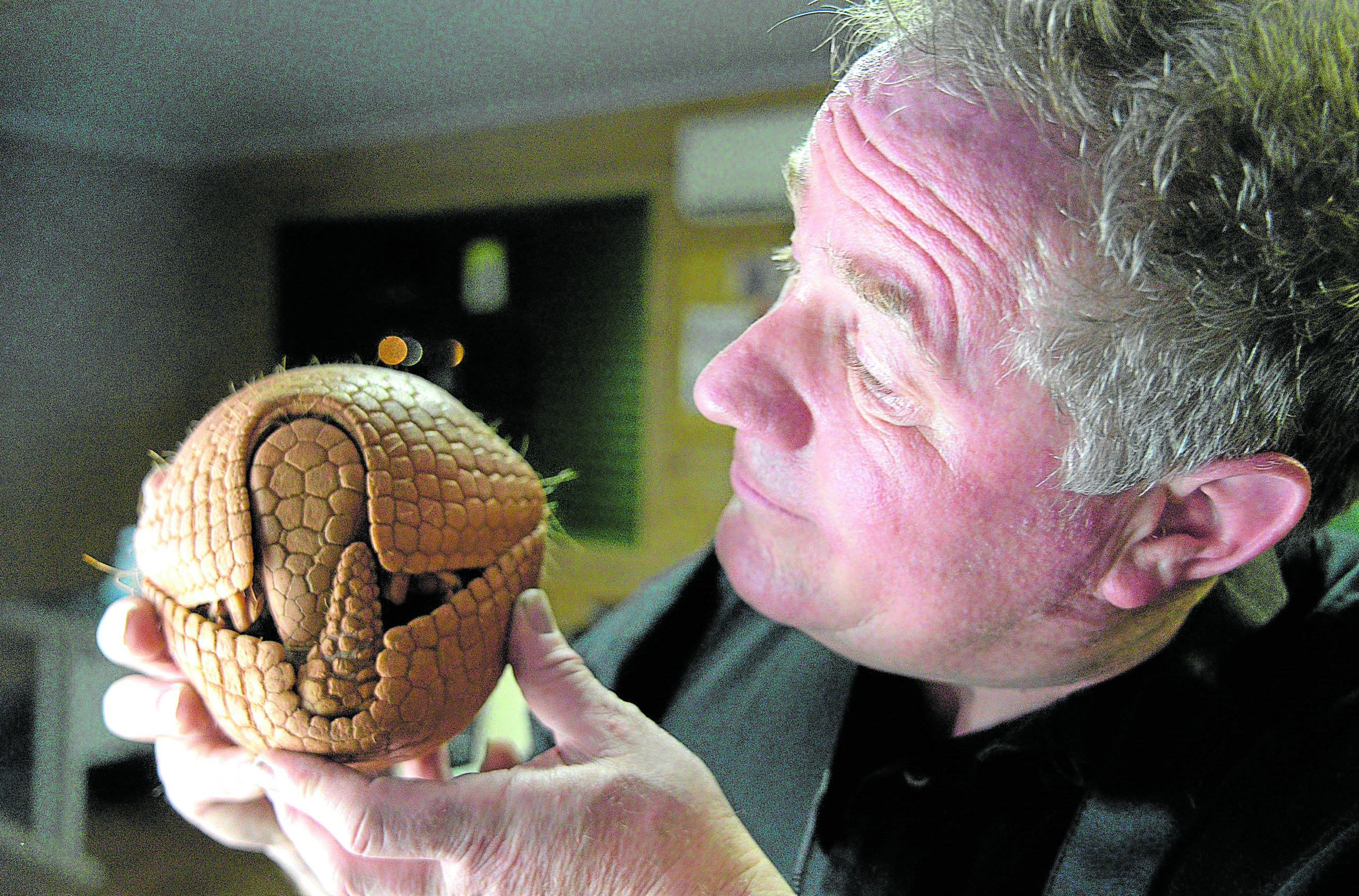

Article continues after this advertisementIn these places, we find Joel interacting with, among others, a three-banded armadillo, an orphaned baby orangutan, a crab-eating macaque, a Bornean rhinoceros, an American pika, a venom-spitting cobra, a gargantuan Amazona manatee, four furry Sumatran tiger cubs, and the largest living and most dangerous bird in the world, the double-wattled cassowary.

Article continues after this advertisementThen, there’s Joel’s memorable 20-second photo session with Kanzi, the “directable” male bonobo chimpanzee who’s known for his advanced linguistic aptitude. (Kanzi shares 98.5-percent genetic compatibility with humans and possesses the comprehension skills of a human toddler.)

The docu’s sophomore season, directed by Chun-Wei Yi, commemorates another record-breaching milestone for the project—the 10,000th entry in the Photo Ark, courtesy of güiña in Chile, considered the smallest wildcat in the Americas.

More than 10,000 species are already in the Photo Ark, but Joel told us in our recent one-on-one chat that his work is far from over.

“We’ll go again once travel restrictions [because of COVID-19] are lifted. It’ll take another 10 years’ worth of work to get to the last 5,000 on our list,” Joel noted. “We figured there are 15,000 of these species in the world, [many of them] in accredited zoos and aquariums. That’s our target.”

Our Q&A with Joel:

How long does it usually take you to prepare for a shoot? Which animal was the most difficult to handle?

That’s a good question. For every shoot, it takes us about one day to prepare—and that’s just on my end. For small animals, it’s no big deal.

But the zoos have to do a little more preparation if we’re photographing big animals, because they have to secure a room, usually with a black or white background. It takes them some time to get the animals in there and get them to get used to it. It’s usually where the animals come in to be fed or go to sleep for the night.

In terms of difficulty, big primates like chimpanzees are very difficult. In fact, there was a time when I used white paper with chimpanzees, which I realized was a stupid thing to do.

The chimps didn’t even enter the room—they just stuck their hands in and ripped all the paper down to shreds. It took them about six seconds to do that. If people want to see it, it’s called “The Chimp Incident,” and it’s on my website, which is joelsartore.com.

Your photos capture the majesty of these endangered creatures. But I noticed that you were nervous when you were taking the picture of the spitting cobra in Java. You had to remind the caretakers not to keep agitating it just to get it in place. What were your scariest and most satisfying moments to date?

I have a healthy amount of respect for animals, regardless of whether they can hurt me or not. With a spitting cobra, you wear a face shield, try not to talk a lot, and keep calm just to get through it.

I work with handlers who know their animals. So, in terms of scary, it’d have to be when I was working as a field photographer of wildlife for National Geographic for 17 years. In those days, I was charged by grizzly bears, elephants and lions.

But now that I’m working in zoos, it’s much calmer and safer. Most of them are used to getting fed extra treats on the day of the shoot. These animals were born and raised in human care, so they’re really not that uptight.

And it’s very satisfying when you get any species to look beautiful, and when you establish good eye contact with them.

Are there other endangered species in Asia you have yet to take photos of?

Yes, there are many. Indonesia, for one, is a country we need to work in a couple more times, mainly for its rare birds and small mammals. We need to get their stories told to the world—that’s the goal. So, thanks to National Geographic, which helps us realize our goal.

When people ask me what my favorite animal is, I always answer, “Well, it is whatever animal is coming up next, whether it’s a minnow, a sparrow, a toad or a bat. They’re all equally amazing in my eyes.”

Taking photos requires patience, resilience and a talent for improvisation, like how you managed the photo session with the armadillo. Did you have these traits growing up?

Yes, I did … since I was a little kid, I was told by my parents. I’m very type A, which means I’m kind of wound up and ready to go all the time. I was the kind of kid who would never go out to play. If I had a lot of homework to do, I’d always do my homework first.

I’m very persistent and, more than anything, driven. I’m not a patient person at all. But I’m patient if I’m waiting for animals to pose (laughs).

That’s a common thing among geographic photographers—we’re fairly driven. I mean, you wouldn’t want everybody to be driven like that. So, I envy my wife, who’s very laid-back. And that’s OK, too.

You spend a lot of time away from home. You miss milestones with your family—like when your daughter moved to a dorm in college. What makes it worth all the personal sacrifice?

I’ve thought about that quite a bit, and I realized I don’t really have a choice. This is the path I’ve taken. I mean, we can rearrange birthdays a little bit (laughs). Would you rather try to save an animal from extinction by telling its story well? It doesn’t take a lot to save many of these animals. We just need good habitat for them and stop persecuting them.

So, if it’s a choice between that and doing something routine at home, I’d have to go for the animal every time.

“Photo Ark” Season 2 premieres at 8:30 p.m. on National Geographic Wild (channels 66/193 on SkyCable; channel 142 on Cignal) on Nov. 18 (Part 1) and Nov. 25 (Part 2).