Why Kristin Scott Thomas owes her career to Prince

Kristin Scott Thomas as Mrs. Danni Danvers

You’d think Anthony Minghella and his breathtaking screen romance “The English Patient” would immediately come to mind if you ask Kristin Scott Thomas to revisit her past as a newbie actress and take stock of her enviable career in the performing arts.

More than her roles in “Four Weddings and a Funeral,” “Gosford Park” and her recent Emmy-nominated turn in “Fleabag,” it was Minghella’s sweeping period piece that first drew attention on a global scale to Dame Kristin’s potent allure as a leading lady of immense skills, charm and gravitas.

When we spoke to Kristin last Thursday to discuss her nasty role in director Ben Wheatley’s visually stunning new version of Daphne du Maurier’s “Rebecca”—first made into a film 80 years ago via Alfred Hitchcock’s first and only Oscar best picture winner—we asked the British actress how far she had evolved as an actress since she appeared in Prince’s 1986 film, “Under the Cherry Moon.”

After all, we can all agree it isn’t every day that Kristin’s name is mentioned alongside that of the Purple One.

To be clear, there were reports that noted Kristin’s alleged “disdain” for the aforementioned film. But our interview with her quite softens the blow. In fact, she looked back at her experience with the iconic music superstar with so much sincerity and affection that it unexpectedly tugged at our heartstrings.

Article continues after this advertisement“He [Prince] was an extraordinary person,” Kristin said. “Well, I hope I’ve evolved because I’m not particularly proud of my performance in that film (laughs). But he was really the first person to give me my first job as an actress in a film… He saw something that no one else saw—and didn’t see for a while, I have a feeling. So, you know, I am eternally grateful for what he did.

Article continues after this advertisement“He became … I hesitate to say friend, because I didn’t know him very well… But he was a regular feature in my life. He would contact me when he came to Europe. He would see my work. He would send me messages. I think he was proud of me.

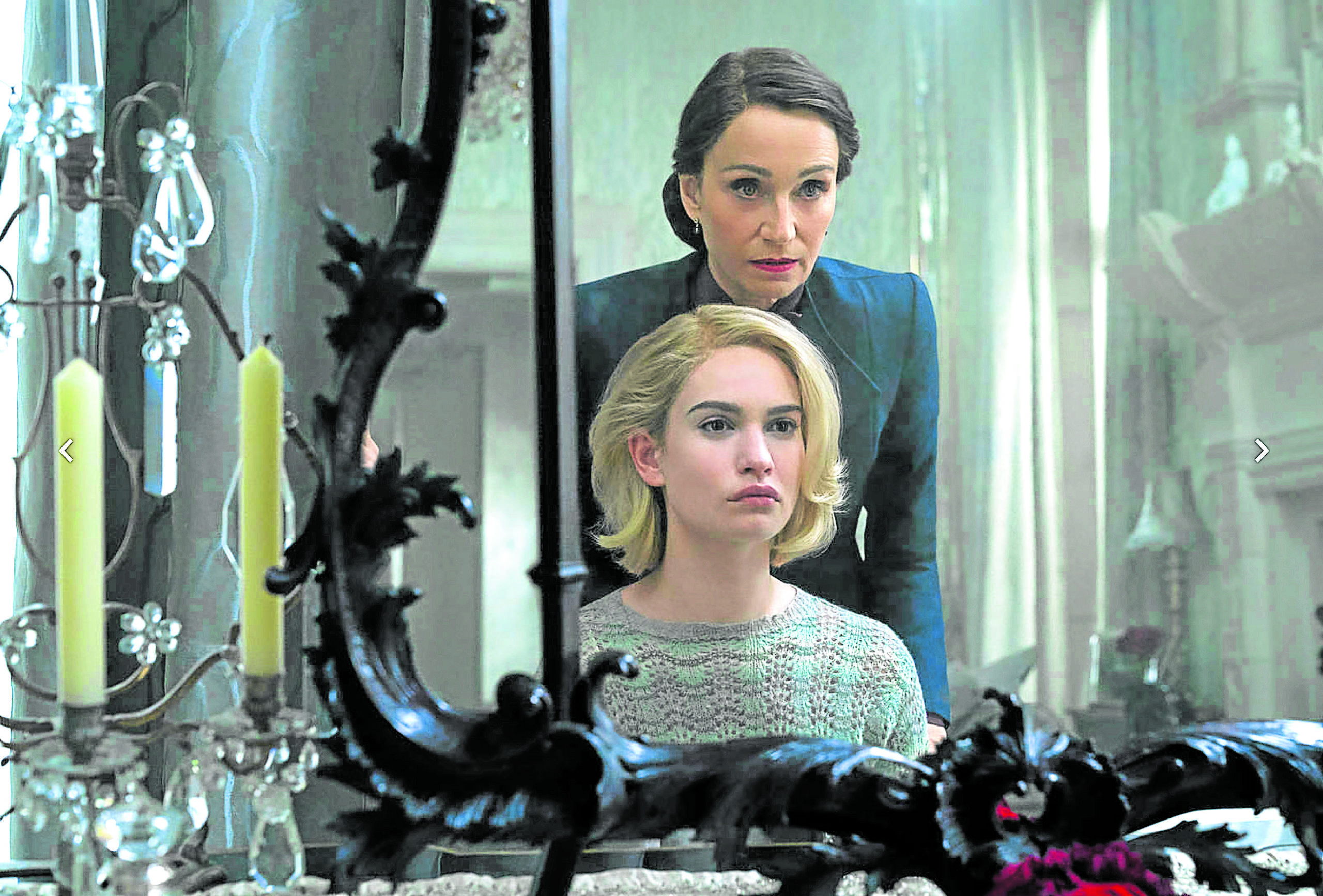

Thomas (standing) as the unwelcoming caretaker and James as the insecure second wife

“He had a certain pride in having been the first person to give me a job, and that makes me proud. We were only 23 when we made that movie. And, you know, life is an endless adventure. So, yeah, I think I have evolved as much as he did since.”

In “Rebecca,” which launches on Netflix this Wednesday, Kristin plays Mrs. Danni Danvers, the unwelcoming housekeeper of the castle-like Manderley mansion, owned by widower Maxim de Winter (Armie Hammer).

Fiercely loyal to Max’s gorgeous first wife, who reportedly perished in a boating accident, Danvers makes life a living hell for Max’s awkward and insecure new wife (Lily James).

Despite all the doom and gloom of the story, Kristin, who turned 60 last May, said that she didn’t have a hard time shaking off the darkness of the character at the end of each shooting day.

“Not in this case, no, because I was surrounded by people who were playing this as a fantasy,” she explained. “This is a ghost story set in a most extraordinary environment. We were inventing the story—OK, no, we were not inventing it because we were merely repeating something that has been done so many times before. But we were creating this world, and it felt like a very defined environment.

“So, when we came off the set, and particularly with Lily, it was all very relaxed and sweet and friendly and kind. There was a huge disconnect from the world of Manderlay, Mrs. Danvers, Mrs. de Winter and the world of caravans. Our beautiful summer’s day in England was disconnected from all of that.”

Asked to talk about the film’s overarching themes, Kristin said, “At the moment, we’re going through a phase where women in general are waking up to the inequalities that are still raging—and this film highlights that.

“In the 1930s, women relied on men. To some degree, they still do, but in this version, a woman is able to react and kick back against it. Whereas in the versions before, the same character was less conscious of those differences.

Hammer (left) and James

Our Q&A with Kristin:

Your body of work features a long string of dramas. Is the adjustment in acting different from when you take part in a gothic horror piece like “Rebecca”?

It’s very much the same mindset, you’re just evolving in a different environment. I really enjoyed the theatricality of it, and some of the drama of it was very exciting for me. I also very much enjoyed the visual elements of the film.

I had no reservations all about the role. In fact, I had been emailing the producer about it when I heard that this was going to be made into a film, saying, “You know, you have to hire me because I have to play Mrs. Danvers. I hesitate to say, ‘I am Mrs. Danvers,’ because that would be very unpleasant (laughs). They didn’t ask me for a very long time. Then, eventually, my agent rang me up and said, ‘Yes, you got the offer.’ I said, ‘Ah, at last!’”

Why is Mrs. Danvers faithful to Maxim’s first wife, Rebecca, almost to the point of obsession?

Because she started to look after Rebecca when she was a little girl. She watched her grow up, she had this incredible maternal relationship with this girl. She adored her from when she was tiny, then watched Rebecca become a teenager, then a young woman, then a married woman. She could see no wrong in whatever she did. She was blinded by love. So, that’s what it is.

She herself has all sorts of frustrations as a woman. She’s unfulfilled, which comes across very strongly in both the novel and our screenplay—somebody who’s only lived for Rebecca and was given nothing back. In the end, Rebecca dies, then this other girl arrives. The disappointment, anger and jealousy are the ones driving her.

We’ve all met people like Mrs. Danvers, who take pleasure in making others feel insignificant. She’s probably overcompensating for the fact that she ended up as a housekeeper … when she could have been lady of the house. She’s had a huge collapse in her status—and that’s when she takes it out on other people. She’s a bully!

Armie Hammer (left) and Lily James in “Rebecca”

The film has been reworked several times already. How will this new version stand out from the rest?

We’re banking very much on the ghostly atmosphere of it. It’s also very different visually—it’s extremely rich and beautiful. In the 2020 version, we’re expressing more strongly the frustration that is implied in the novel … of being born female and of having to simply rely on the presence or absence of a man.

In Mrs. Danvers’ case, it’s the latter, because nobody really knows what happened to Mr. Danvers, although presumably there was one. He must have died in the first World War. So many women of that generation in that age group lost their partners, husbands, brothers or fathers in the war. So she is manless.

Being manless in those days made life extremely difficult for many women. Now we can see that more clearly. We have a better distance from it, so we’re able to consider it and weigh up what that actually means—I think that’s where this film differs from other remakes.

Your version of Mrs. Danvers is scarier than the original because of the element of ambiguity—there’s a sinister nature that isn’t as obviously depicted. We feel that the stakes are high, but we don’t quite know what she’s up to. Was it a conscious decision on your part to veer away from how she was first portrayed?

The only conscious decision we made that veered away from the original version was with my hairdo. Because I wanted much of all that hair away, and we thought it looked too much like the hair worn by Judith Anderson (who played Mrs. Danvers in the Hitchcock film).

But then, the one that really scared me personally was the version of Anna Massey, who portrayed Mrs. Danvers in the BBC miniseries in 1979—that was really scary! So, it wasn’t difficult for me to sort of move away from that.

You know, the part is so rich. And when you have a very few scenes in which to nail something, you have to be very precise—which is what I like doing.

What does the audience take away from watching the film?

Don’t hold on to the past, I think that’s the message (laughs). Let it go. Otherwise, things will come to a sticky end—because Mrs. Danvers is the absolute example of somebody clinging to a memory, to something that doesn’t exist. It’s very unhealthy.