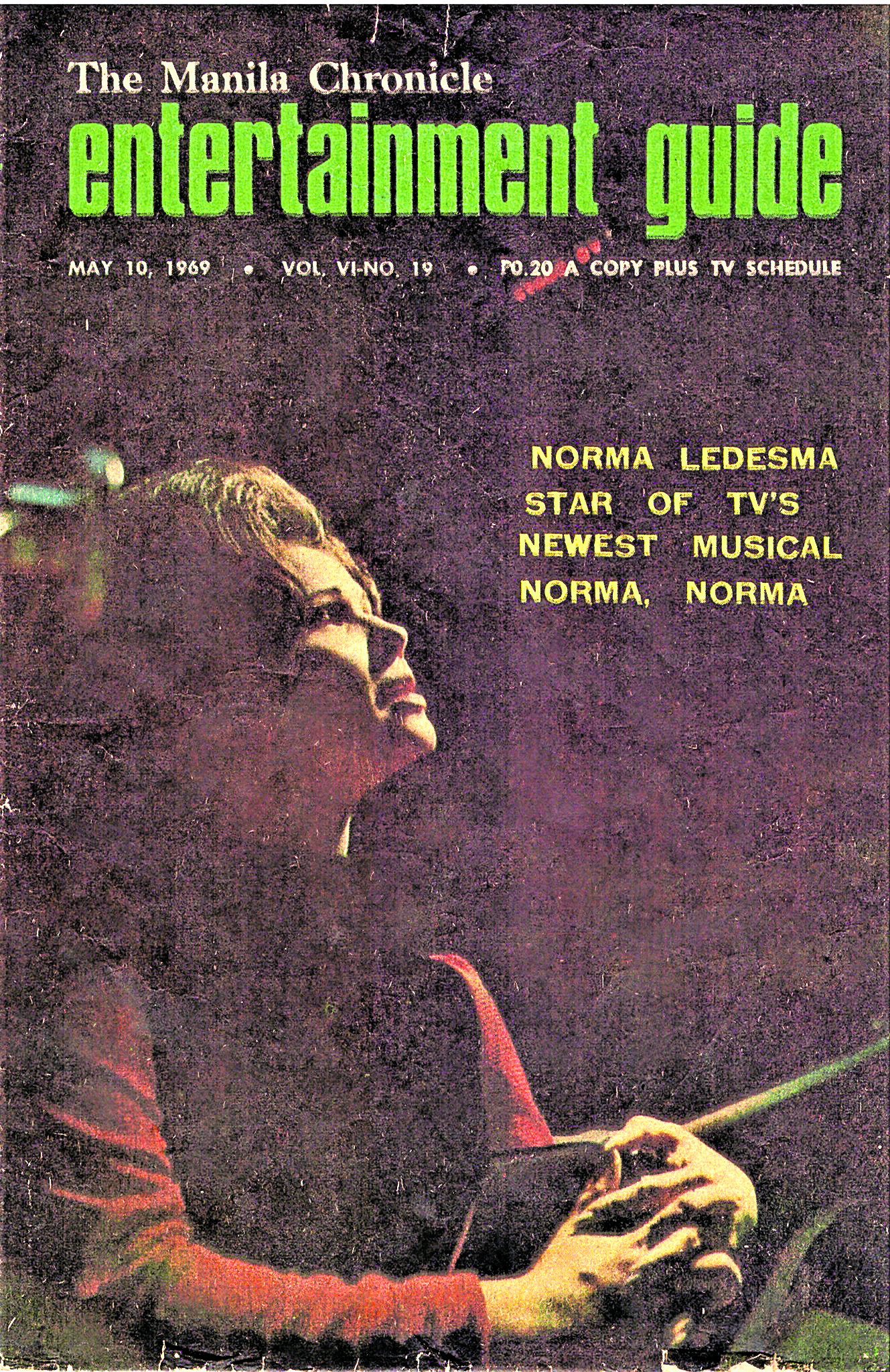

Norma Ledesma on the cover of The Manila Chronicle in 1969

The OPM Archive Foundation, a group dedicated to indexing and conserving local musical artifacts, is urging artists and industry workers to submit memorabilia and other items that could help piece together the “colorful mosaic” that is original Pilipino music.

The project—founded by singer-actress Celeste Legaspi, TV writer-artist Tats Rejante Manahan, publicist-producer Girlie Rodis and TV writer-director Lyca Benitez Brown—is still a work in progress.

But once it’s ready, the archive, which will be housed inside the Filipinas Heritage Library of the Ayala Museum complex, will make available a curated collection of photos, posters, musical scores, books, press releases, songs hits, album covers, scripts, audio and video recordings and magazines. “I have worked with Tats on shows for many decades, so we have lots of memorabilia and documents. Last year, she came up with this idea that we should have an archive, so that we could preserve or document OPM; so that future Filipinos can enjoy and learn more about it,” Legaspi said in a recent video press conference.

Winners of first Metropop music fest

But more than a walk down memory lane, the archive envisions itself as a valuable source for future studies and research about the history and development of OPM through the years. “Music isn’t a dead heritage—it’s a living one, it changes with the times. And it’s for this reason we wanted to have an archive. So that people, particularly the future generations, who wish to study OPM can see how it has evolved,” Manahan said, adding that each song, each memento is a window to how things were at a given time or place.

“What’s the story behind ‘Ang Huling El Bimbo’? Or of ‘Annie Batungbakal’? These are actually social records of specific times,” she added. “Those of you willing to donate, we ask that you please share with us, not only your music, but also your stories, memories and narratives. Where did you first hear this piece of music? How did it affect you? What was going on during that time?”

The original plan was to cull materials from the 1970s to the 1990s. But for future-proofing purposes, the team decided to expand the archive’s scope by including the immediate forerunners of OPM in the 1960s and extending it to the present generation, “with the hope that future generations continue in keeping the archive moving, thus creating a living archive.”

Celeste Legaspi (center) with Bodjie Pascua and Gigi Dueñas

Submissions can be of any genre, language and place of origin as long as they’re created and performed by Filipino artists. The materials will then be evaluated by a group of curators to see if they meet the archive’s content considerations (relevance, reputation, authenticity, originality and impact) and technical criteria (physical condition and clarity of visuals, or sound in recordings).

“These will be arranged according to decades—each one of which will be divided into different subcategories, including genres or scenes,” explained the group’s vice president, singer and music teacher Krina Cayabyab. Other officers include Moy Ortiz of vocal ensemble The CompanY, Dinah Remolacio and Chevy Salvador.

Earlier this year, before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the group hoped to hold a concert and an exhibit to formally launch the archive and reopen the Filipinas Heritage Library, which was undergoing renovation, in December. “We were very excited,” Manahan said. “But everything’s indefinite at the moment because of the lockdown.”

At the recital of the first batch of 14k

“We’re collecting as much as we can. After that, we will consult with our curators to see what we have and determine what else we can and should pursue,” Legaspi added.

While the opening of the physical archive remains to be seen, given the current climate, its official website—which contains digitized versions of select memorabilia—is already up and offers a peek of what people can expect. Visit OPMarchive.com for more information.

From left: Geneva Cruz, Regine Velasquez and Louie Heredia