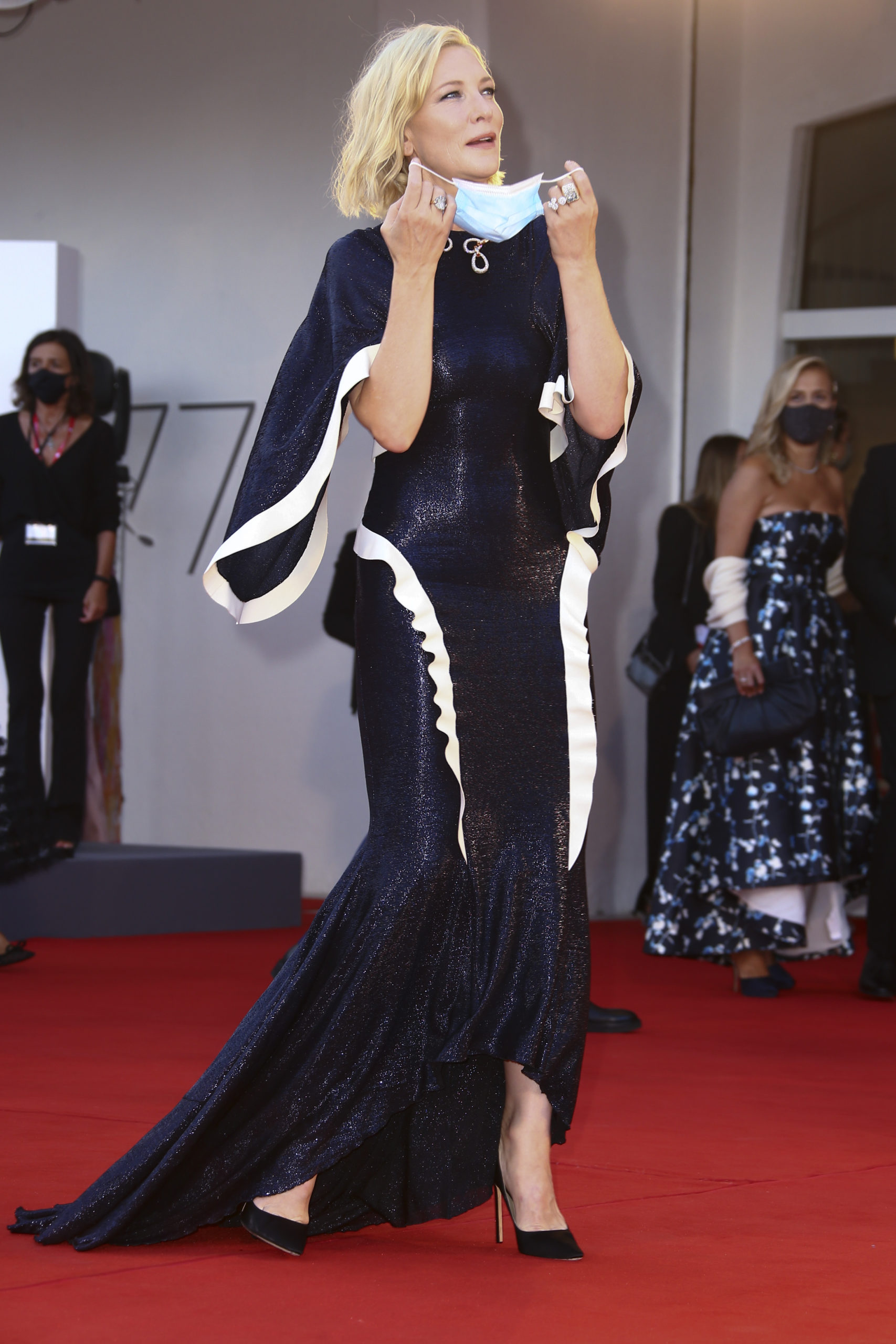

Jury president Cate Blanchett poses for photographers upon arrival at the opening ceremony of the 77th edition of the Venice Film Festival in Venice, Italy, Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2020. (Photo by Joel C Ryan/Invision/AP)

VENICE — The beachfront terrace at the Excelsior Hotel, usually hopping with movie industry VIPs and minor celebrities, is pleasantly quiet.

The red carpet has a three-meter-high (ten-foot) wall blocking the public’s view. Veteran film-goers walk away dejected after being told they had to reserve seats online, well in advance.

Welcome to the Venice Film Festival in the time of coronavirus.

The world’s oldest film festival opened Wednesday under a slew of anti-COVID protocols, with the few A-list celebrities making the trip wearing face masks and the general public largely absent.

Paparazzi who in past years rented boats to chase stars as they crossed the lagoon to the Lido filmed the opening arrivals from special, socially-distanced spots along the red carpet. Masked guards took temperatures at nearly every turn, and no jostling, crowding or cramming was allowed.

It’s all part of the measures imposed by Venice organizers to try to safely host the first major in-person festival of the COVID-19 era when others canceled or went online.

Guests wear face masks and sit at a safe distance as they follow the opening ceremony of the 77th edition of the Venice Film Festival at Venice Lido, Italy, Wednesday, Sep. 2, 2020. The Venice Film Festival will go from Sept. 2 through Sept. 12. Italy was among the countries hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic, and the festival will serve as a celebration of its re-opening and a sign that the film world, largely on pause since March, is coming back as well.(AP Photo/Domenico Stinellis)

That the festival is happening at all is significant, given Italy was the first country in the West to be hit hard by the virus.

But Italy also largely brought infections under control with a rigid lockdown and continued vigilance — measures that festival organizers have embraced and enhanced.

“We feel the responsibility (of) being the first one. We know the festival of Venice will be a sort of test for everybody,” said festival director Alberto Barbera.

“We worked a lot on strict plans of safety measures to ensure that everybody who attended the festival would be safe until the end. And if it works like we hope, everybody can learn from our experience.”

Usually, the public is warmly welcomed at Venice both indoors and out: They flock to screenings, and wait in the sun for hours to secure a spot along the red carpet, standing ten-deep to catch a glimpse of celebrities making their entrances.

This year, a huge wall was erected to block their view and dissuade them from gathering, though some dedicated fans crowded at the entrances and peeked through the fencing to try to catch a glimpse of Matt Dillon or Tilda Swinton as they arrived for the opening ceremony.

Swinton, who was awarded a lifetime achievement Golden Lion on Wednesday, gave them a treat for their persistence, sporting a gilded Venetian-style masquerade mask and offering a tribute to the lagoon city for having dared to have the festival at all.

“I would like to thank our sublime Venice and all who sail in her, the most venerable and majestic film festival on Earth, for raising her banner this year,” she said in her acceptance speech. “Viva Venezia! Cinema Cinema Cinema! Wakanda Forever!” she said, citing the salute made famous by the late “Black Panther” star Chadwick Boseman.

The pandemic hit the film industry hard, forcing the closure of theaters as well as the cancellation of production on sets around the globe. Venice has tried to offer the industry a source of hope in a rebirth, but the absence of Hollywood films has deprived the festival of much of its star power and deal-making pull.

The terrace bar at the Excelsior is usually ground-zero for the schmoozing and movie rights deals which are key parts of the festival marketplace, with gala parties on the opening and closing night.

This year, as the sun set on the terrace ahead of the opening night, a few festival-goers in black tie and gowns sipped cocktails as hotel guests returned from the beach in their bathing suits. No big parties were planned.

Jury president Cate Blanchett said it was “miraculous” that the festival came off at all.

But for veteran Venice festival-goers, the new restrictions created unprecedented hurdles that threatened to shut them out.

Maria Luisa Biffis, who lives part-time in Venice, said for years she would come to the festival on the first day to pick up the program and scope out which films she wanted to see over the following 10 days. She’d then come back to buy tickets and queue on the day of the screening to get in.

“Now you can only buy tickets online,” Biffis said as she walked away from the help desk after realizing she’d been shut out. “I’m on vacation, and I don’t have a computer.”

In addition, seating is limited to ensure at least every two or three seats are vacant, meaning some films have already sold out, particularly those that are screening in the two new sought-after open-air venues.

“I would have liked to have seen the new Segre one,” Biffis said, referring to the pre-opening film “Molecules” by Italian director Andrea Segre. “I’ll see if there’s anything else I can get.”

She is not the only one nostalgic for the way things used to be.

Carlo Lazzarini has worked at the Venice film festival for 22 years, this year as chief inspector for one of the smaller screening venues. He is so well-known and well-loved by veteran festival-goers that they bring him bottles of wine and gifts from home when they come back each year.

“The beautiful thing about the festival was the embrace with the public, and the joy in meeting them every year,” Lazzarini said as he helped guests negotiate the online ticketing system at a Wednesday morning screening. “But unfortunately, COVID has massacred our social relations.”