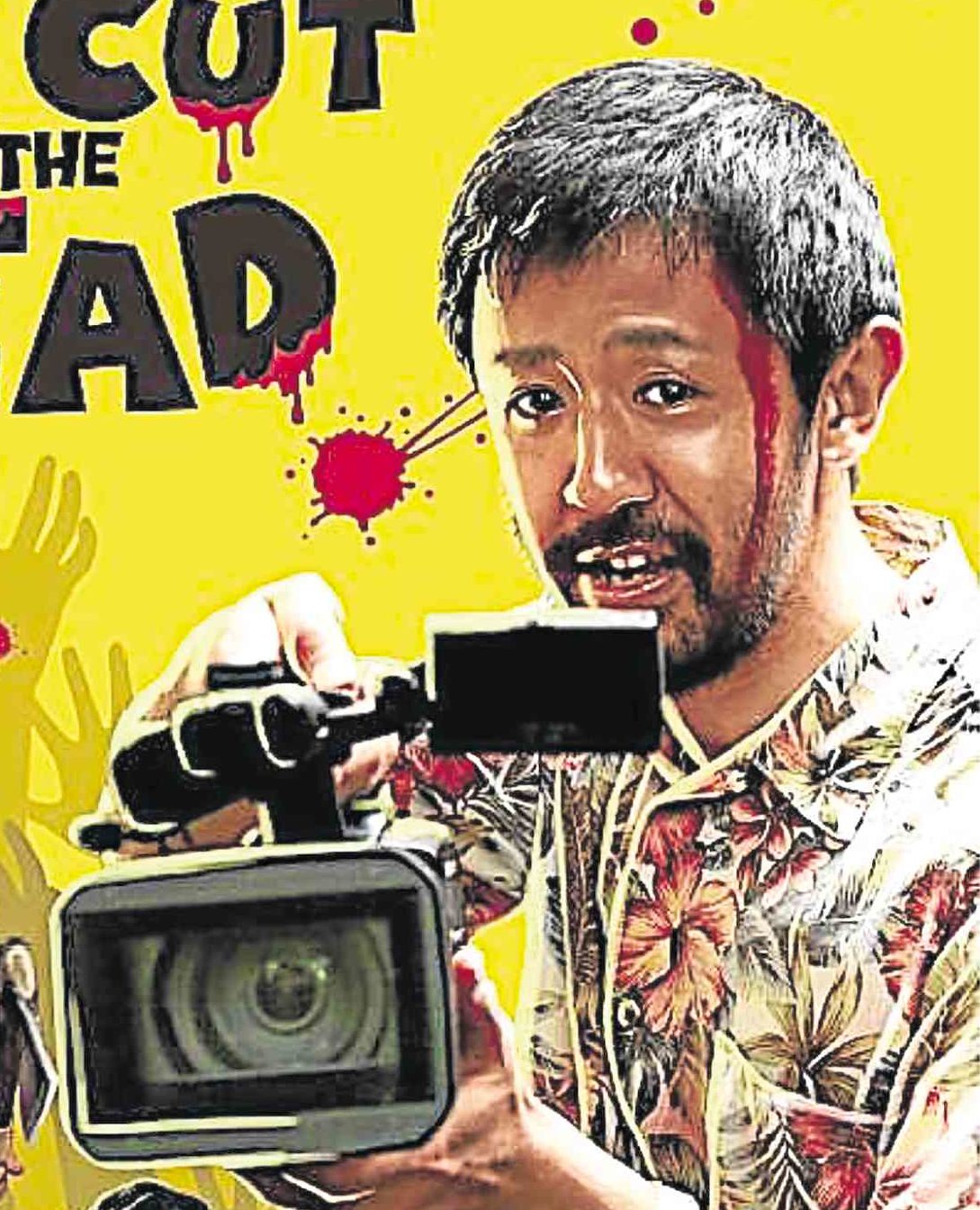

Yukuzi Akiyama (left) and Kazuaki Nagaya in “One Cut of the Dead”

The 22nd edition of the annual Eigasai event is a delectable cinematic brew made up of 17 contemporary Japanese films that will be screened in seven major cities nationwide beginning today till Aug. 25.

The lineup is long and impressive—and, even better, entrance to screenings at Shangri-La’s Red Carpet Theater, where Eigasai entries will be shown from July 3 to 14, are priced at a very affordable P100 per ticket.

There are a string of must-see titles, including Katsumi Nojiri’s suicide tale “Lying to Mom,” Yukihiko Tsutsumi’s tragic divorce story “The House Where the Mermaid Sleeps,” Hirokazu Koreeda’s existentialist drama “After the Storm,” Katsuo Fukuzawa’s police procedural “The Crimes That Bind,” Mamoru Hosoda’s Oscar-nominated animation “Mirai” and Bernard Rose’s “Samurai Marathon 1855.”

Of particular interest to film buffs and genre aficionados alike is Shinichiro Ueda’s “One Cut of the Dead.”

It won’t take long before you’ll see beyond the kitschy hilarity of watching the film crew of a low-budget zombie flick struggling to stay alive, when real zombies suddenly come from out of nowhere and start chasing them around.

As the film pays rousing tribute to the trials and exhilarating triumphs of filmmaking, you’ll be entertained even more by the way the production inventively plays out like a clever send-up of the zombie genre.

Takayuki Hamatsu

High-strung director Higurashi (Takayuki Hamatsu) is having a bad day. His penchant for authenticity and real emotions, not to mention actors who rely on eyedrops for their crying scenes, is slowing him down.

After 42 takes, the shoot is stuck in one sequence because its lead actress Chinatsu (Yukuzi Akiyama) doesn’t look scared enough, even with helpful coaching from her leading man Ko (Kazuaki Nagaya) and production hand Nao (Harumi Shuhama), who brings out the “ax-wielding monster slayer” in her when she finds herself put through the wringer.

Higurashi’s production takes a bizarre but “creatively fortuitous” twist when zombies begin to show up at the shooting site—a former water filtration facility that is said to be haunted.

Urban legend says that during World War II in the ’40s, the building was used by Japanese soldiers as a place for experimentation, to bring the dead back to life!

Soon, members of Higurashi’s crew fall victim to the flesh-nibbling creatures, but the uncompromising director is only too happy to see the “impact” of the terrifying turn of events on Chinatsu’s performance—finally, the apathetic actress isn’t as hammy anymore!

If you think that’s all there is to this zombie story, you’ve got another think coming.

Harumi Shuhama

The aforesaid tale is just a chunk of a three-part story that also examines the excesses of reality TV programming that has become part and parcel of pop culture these days.

In this film’s behind-the-scenes segment, which took place one month before its actual shoot, a director (Hamatsu) is tasked to helm a horror drama for the Zombie Channel.

To raise the stakes and up the reality show’s crowd-drawing ante, Higurashi must shoot his 30-minute zombie flick during a live broadcast using just one camera, and with no cuts—for 30 minutes!

The movie’s third section and a fourth one, shown as the credits roll, astutely demonstrate the rigorous process that makes all the circuitous and complicated elements of filmmaking come together.

The movie reminded us of the theme that frames “Sunday in the Park with George,” the Stephen Sondheim production that we saw on Broadway a couple of years ago.

In it, the popular showtune “Putting It Together” is sung by the musically proficient Jake Gyllenhaal.

The ditty, a loving tribute to art and its stubborn practitioners, couldn’t have said it better: Art isn’t easy/ Putting it together, bit by bit/ Every little detail plays a part/ First of all, you need a good foundation/ Otherwise it’s risky from the start/ A vision’s just a vision if it’s only in your head/ If no one gets to hear it, it’s as good as dead.

Spot on.