Mahershala Ali shares his thoughts on racism and the ‘Green Book’

LOS ANGELES—“It’s bubble-wrapped right now. I just moved so I haven’t put it out yet,” Mahershala Ali said about the Oscar best supporting actor trophy he got for his performance in Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlighting.”

He might get another Oscar best supporting actor nomination for his acclaimed performance in Peter “Pete” Farrelly’s “Green Book.” Mahershala already earned a best supporting actor nod from the Golden Globe Awards this year.

Mahershala, short for his first full name Mahershalalhashbaz (the longest proper name in the Bible), said his wife, Amatus-Sami Karim, never called him by his name. Instead, she calls him “Hey.” He added with a grin, “My wife never says my name. Never, like ever. If she does, I’m in trouble for something (laughs).”

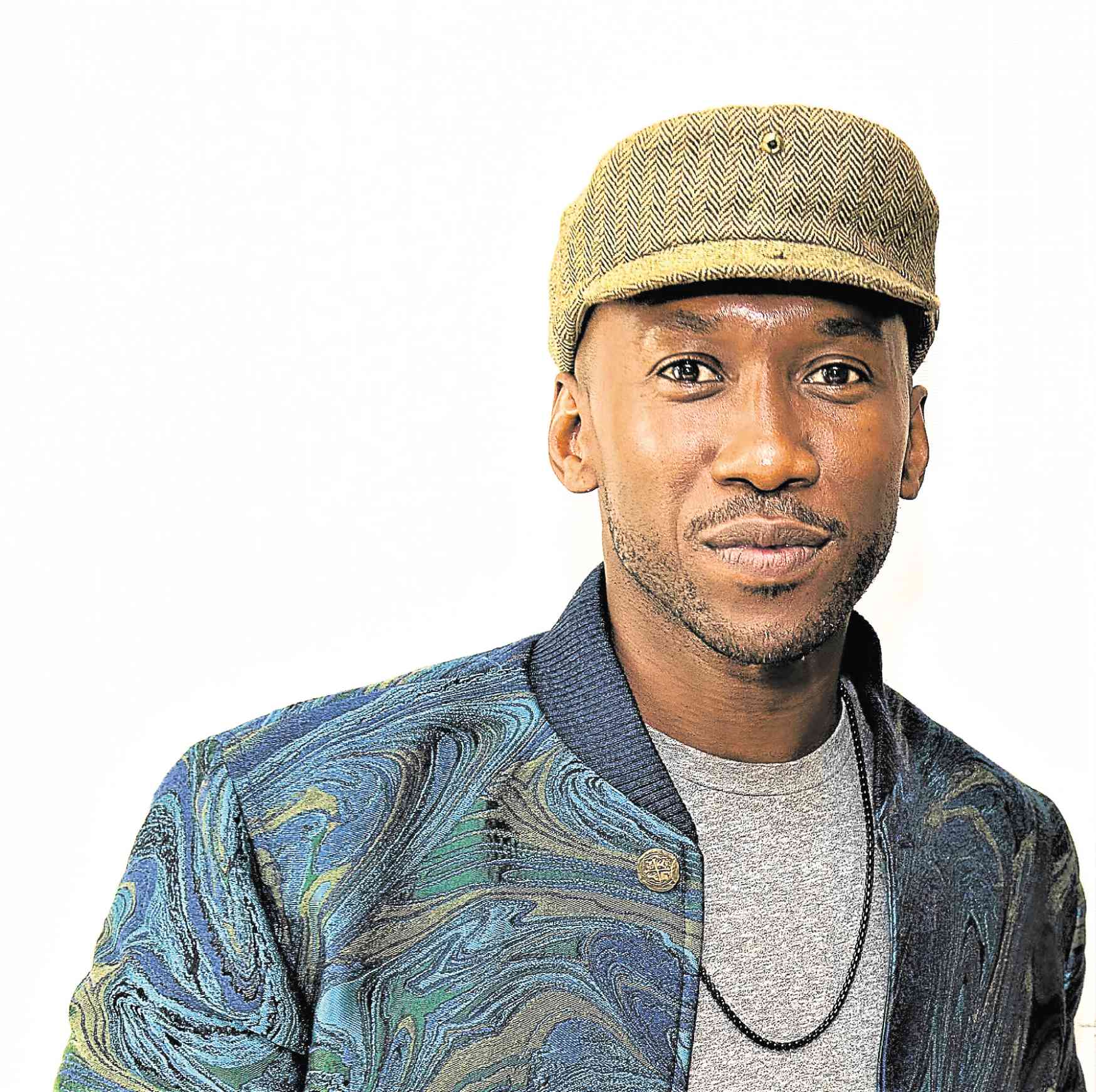

“I was going for the peacock look,” he quipped when asked about his colorful jacket by Etro.

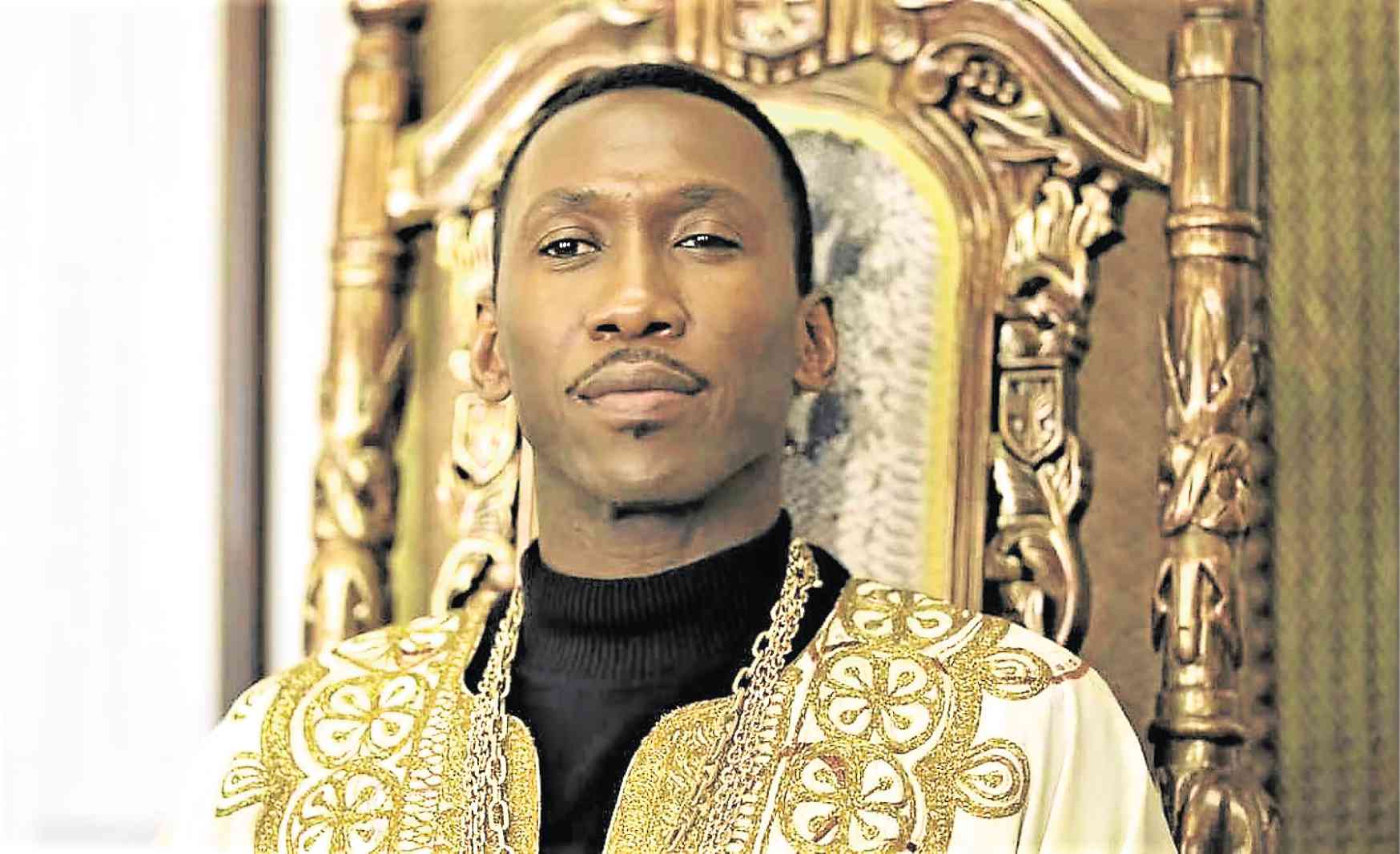

In “Green Book,” Mahershala is a real-life pompous concert pianist, Don Shirley, who hires a tough guy (Tony Lip, played by Viggo Mortensen) as his chauffeur and bodyguard on an eight-week show tour in the South. It’s the ’60s, a segregation era when there is such a thing as “Green Book,” a guide for black travelers on where they can stay and eat.

Article continues after this advertisementMahershala is superb as a jazz and classical pianist, pretentious on the surface, but a vulnerable and a tortured soul inside. Both he and Viggo make “Green Book” compelling to watch from start to finish.

Article continues after this advertisementExcerpts from our interview:

Have you experienced something like in the movie—what Don Shirley went through, where you were not made to feel welcome? Oh yeah. A couple of weeks ago in London. Pete Farrelly was with me. They asked me why I was there essentially, after taking everyone else’s dinner order, then asked to see some information on me … But they know. And so, I got upset and I left. And Pete got upset.

So, it’s totally relevant. It happens all the time. I’m famous with a Master’s Degree and an Oscar. So, imagine if you don’t have any of that and you’re just there trying to enjoy dinner. Or you’ve been invited by someone who is a member there.

That happened to me when I was sharing this movie at the London Film Festival. So that’s normal, though.

And it hits me in a way because I, like so many, the only way to have a fairly smooth experience as a person of color, at least a black man in this country, is to get famous.

I don’t mean that you forget you’re black, but you remember what that means to other people once they’re not excited to see you, when you have these moments where people are not aware of who you are. And something comes out that is clearly a moment of discrimination. It can be really jarring.

Do you experience discrimination on the red carpet? I’m just glad when I step on the red carpet, the cameras keep flashing a little longer now (laughs). I remember so many times I’d get on that red carpet and b-r-r-r-r-r-r, cameras lighting up, and they’d get to me, like click (just one shot taken of him). “Alright, you can move along.”

It’s really humbling (laughs). So many people experience that, like get pushed out of the way to get to the next person.

Did you know about Don Shirley before making this film? No, I hadn’t heard of Don Shirley before. I wasn’t familiar with him, which is part of the story in a strange way.

Don Shirley was stuck in this pocket where he was making pop music that didn’t really speak to even the type of jazz that he would have wanted to do. It was a career of compromise, which is in part what attracted me to the story.

We get very caught up in the more overt racial elements of the story, but the deeper story underneath is about someone aspiring to be something that he’s not free to be.

So I don’t know if the music that he made was something that necessarily would have cut through the jazz of that time to be elevated amongst the Coltranes of the world and these other jazz artists. Because he wasn’t necessarily going all in, fully committed to the type of music that could penetrate in that way.

And how much of the piano playing was done by you or movie magic?

We had to approach it like, you’re playing Chopin, and somebody who is a prodigy. And I’m not going to learn to play Chopin in that way in two or three months, either. So we had to approach it like you would approach a stunt and learn as much as I could and use whatever was usable that was not going to disrupt the experience of the audience.

It had to feel cohesive, believable and truthful.

And how much did you know about the “Green Book” when you were growing up? I hadn’t heard of the “Green Book.” We’re always in a time where we’re unaware of our blind spots as a culture. So there are things that are going on right now that 10 or 20 years from now, we’ll be able to look back and say, “I can’t believe we were doing this, that and the other.” And be surprised at the people who went along with it.

The “Green Book” is telling me how to stay out of your way (laughs) so that I don’t die, right? So I don’t disrupt you. And that’s the black experience compared to the white experience. You can’t point to a year where that stops, where it says, “Now you, black man, go out and enjoy the world and be free, explore. Come see this, welcome to our store. Come buy our products.”

You can’t point to that time when it was great for us. That’s the power of this story.

I got to watch the first episodes of Season 3 of “True Detective” where you play the lead role, detective Wayne Hays. How was that experience of playing different versions of your character at three different times in his life? It was really hard. But I wanted to do it because I knew it was a challenge. Originally, I was not offered that part. I asked to play that part. I sent Nic (Pizzolatto, creator) some pictures of my grandfather, who was a state police officer in California in the ’60s and ’70s. I just wanted to affirm what I was saying about how I felt about the story and how good I felt the story could be if that character was African-American.

I’m grateful for that experience. It was the hardest thing that I’ve ever done in my life. Up to that point, the hardest thing I’d ever done was “Green Book” (laughs). I feel like a better actor and, I hope, a better person. Certainly, I think it aged me.

What were you taught about racism when you were growing up? I was always told that I had to be twice as good to be considered equal. And sometimes, you’d hear you had to be 10 times as good to be considered equal. And so I’ve always felt a lot of pressure to be successful. Not from the standpoint of making them happy, but they’re trying to teach you that so that you can go beyond surviving and to have a life, own a home, be able to have a family, buy groceries and not live check to check.

You became a father last year. How has that changed your life? It’s the most important thing in the world. Parenthood really just puts things in perspective. Even in the way you think about your mortality is just different.

You think about what you want to leave your kids. Not just the material things, but the lessons and the things that you want them to avoid, if possible. But, most importantly, the things that you want to instill in them and leave them with.

Being a parent made me more reflective in a certain way. More conscious of my actions. So you’re always on as a teacher, as a dad, every moment.

E-mail the columnist at [email protected]. Follow him at https://twitter.com/nepalesruben.