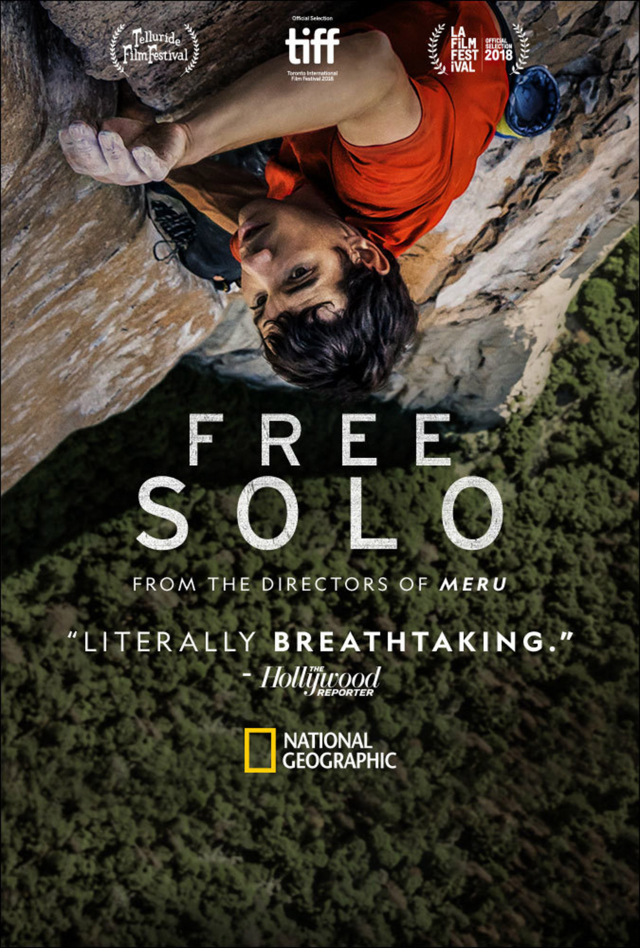

‘Free Solo’ is in US theaters now, in Canada starting October 12 and in the UK in December. Image: Courtesy of National Geographic

Imagine climbing a 900-meter (3,000-foot) granite wall without ropes and almost nothing to grip, moving slowly and perilously upward for four hours.

A brave soul named Alex Honnold completed such a climb and lived to tell the tale.

Honnold was 31 when he pulled off the feat of scaling El Capitan, a vertical rock formation in Yosemite National Park in California, in June 2017 in a drama that is now the subject of a National Geographic documentary. The film is in US theaters now, in Canada starting October 12 and in the UK in December.

“So delighted,” Honnold said once he reached the top, the climax of the film “Free Solo,” which narrates the climb and his preparations for it.

Free solo climbing is an extreme technique practiced only by the most experienced climbers. They scale mountains with their bare hands. Many die trying.

One climber quoted in the film put it this way: It’s so difficult and dangerous that it’s as if the penalty for Olympic athletes were death if they failed to win a gold medal every time they competed.

A filming team arrayed along the climbing path — they did use ropes — accompanied Honnold. A drone and two fixed cameras were also used. It’s a terrifying thing to watch.

In some places the rock looks practically smooth, leaving Honnold with nothing more than seemingly invisible bumps and other irregularities in the mountain’s surface to get a toehold and hoist himself upward.

At times he can squeeze his fingers into a crack or work his thumb into a small hole. One particularly tricky spot is known as a “Boulder Problem.” There, Honnold has to perform a complicated set of arm and leg movements to keep moving ahead.

In months of training, working with a rope, he learned to execute those moves to perfection.

Still, on the day of the big climb, one cameraman looked away — he couldn’t watch — as Honnold struggled to cling to the granite wall.

Fear is everywhere in the film. Honnold himself is heard calling El Capitan “frickin’ scary.” The production team spent the whole time holding their breaths against the nightmarish prospect of a fall.

But Honnold seemed so calm as he faced all this that researchers wondered if there was something different about his brain.

Dying on camera

With this in mind, Honnold underwent an MRI in 2016 as he got ready for the ascent. That test, which is documented in the movie, shows that a part of the brain that was once usually associated with fear — the amygdala — did not activate when he was shown violent or frightening images. It was as if he were incapable of feeling afraid.

But, according to the latest research, the amygdala is no longer considered the fear center of the brain. Instead, it activates when a person sees something unfamiliar — whether positive, neutral or negative. And fear is expressed throughout the brain, not just the amygdala, according to Lisa Barrett, an emeritus professor of psychology at Northeastern University and the author of a recent article on the brain region.

Honnold himself said he knows what it is to be afraid.

“I’m afraid of death, I’m afraid of danger, I’m afraid of pain. I used to be very afraid of public speaking,” he told AFP Tuesday on the sidelines of a pre-screening of the film in Washington.

His explanation of how he conquered fear is simpler. “To me, it just shows what 10 years of preparation and practice and de-sensitization does,” he said. Hard work has taught him to tame his feelings.

For years he climbed El Capitan with the aid of ropes, recording all of his movements. He was in great physical shape for the solo climb.

The film suggests that Honnold’s determination borders on obsession, to the point of his neglecting his girlfriend, Sanni McCandless. She calls him “brutally honest” and a “weird dude.”

She recalled how he reacted nonchalantly to news that a climber friend had died in a fall.

“What did she expect?” Honnold asked of the deceased friend’s wife, according to McCandless. Honnold himself says he does not understand how his own death would affect other people.

“This is the life he wants,” said the documentary’s director, Chai Vasarhelyi, who co-directed it with her husband Jimmy Chin, a climber and photographer. “He’s thought about mortality deeply. He’s constructed his entire existence to have this life.”

There was one thing Honnold did worry about: falling in front of the camera.

He said it would be “kind of okay if I’m by myself” but “kind of messed up” if it happened in front of his friends. “Nobody wants to see that,” he said. NVG

RELATED STORIES:

US park Yosemite partially closed as deadly fire rages

Business owners, visitors rejoice as Yosemite reopens