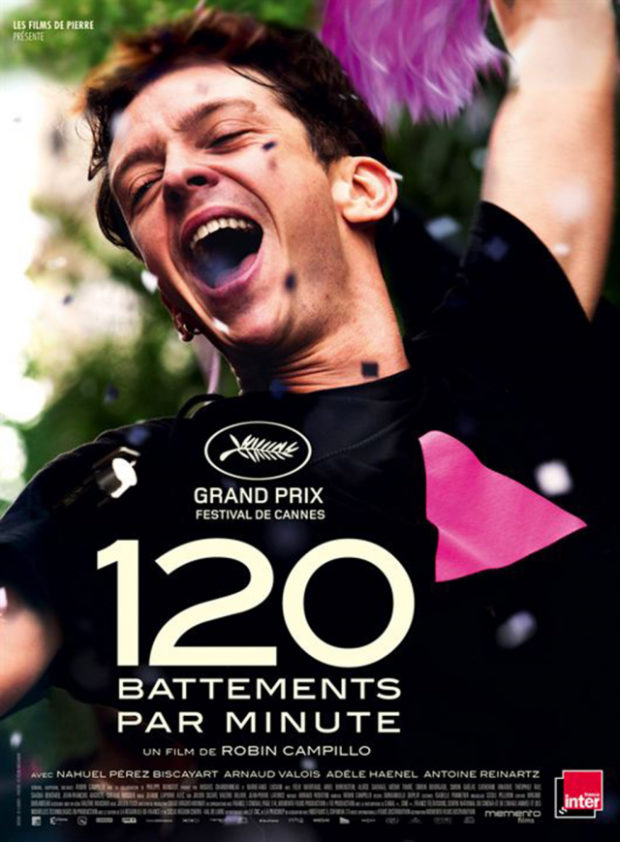

One year after the French AIDS activism movie “120 BPM” emerged as a breakout hit from Cannes, industry insiders say movies from around the world are finally showing homosexuality, not as a burden or an affliction. © Courtesy of Memento Films Distribution

No fewer than 14 gay-themed movies are showing at Cannes — double the number last year — but the world’s top film festival is increasingly spotlighting LGBT characters’ humanity rather than fixating on their sexuality.

One year after the French AIDS activism movie “120 BPM (Beats Per Minute)” emerged as a breakout hit from Cannes and scooped the Grand Jury prize, industry insiders say movies from around the world are finally showing homosexuality, not as a burden or an affliction.

“We’ve passed a milestone: we finally got past the ‘coming out’ movies and the ‘painful problems of homosexuality’. It’s great!” critic Franck Finance-Madureira, organiser of the independent Queer Palm prize for gay-themed movies at the festival, told AFP.

“You’ve got twice the number of LGBT films than usual but the variety of subjects is what’s really key.”

After the Chilean transgender drama “A Fantastic Woman” won the Oscar for best foreign language picture in March and gay coming-of-age tale “Call Me By Your Name” won screenplay honours, the gay movies of Cannes also skip across genre and national borders.

Unique gay identity?

The thriller “Knife + Heart” stars French actress and singer Vanessa Paradis as a producer of gay porn movies who loses one of her actors to a murderer.

And French feature “Sorry Angel” by Christophe Honore is a tender gay love story set at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Honore, who has long given gay characters pride of place in his films, told AFP that same-sex relationships on screen were often caricatures that homed in on a purported “unique identity” of gay people.

“It’s something you have to get past. When you are dealing with the sexuality of the majority (heterosexuality), that’s not an issue but it often is when you’re talking about two men,” he said.

He also condemned as “unbearable” any comparison drawn between his film and “120 BPM”.

“When people compare the two, it’s because there’s a homosexual theme…. That expresses real discrimination,” Honore said.

Underlining the ongoing struggle of gay people in much of the world, Kenya banned the homegrown romance of two teenage girls, “Rafiki”, just days before the festival.

The Kenyan Film Classification Board, Ezekiel Mutua, a self-styled “fervent moral crusader”, slammed its “happy ending” and for showing “the resilience of youngsters involved in lesbianism”.

Despite homosexuality being a massive taboo subject in most of Africa, “Rafiki” director Wanuri Kahiu insisted she never meant to cause a scandal.

“The love scenes are actually cute, they are fumbling and naive, they don’t even take off their clothes,” she said.

“The girls would not know what to do. It was about their innocence,” she said.

Keeping the spotlight on young LGBT characters, “Girl” by Belgian filmmaker Lukas Dhont, tells the story of 15-year-old Lara, who was born a boy and dreams of becoming a star dancer.

Beyond examining the process of coming to terms with her transgender identity, the film is also a tender exploration of the relationship between a father and his child.

And Spanish film “Carmen and Lola” features two gypsy girls who fall for each other.

‘Reflection of real life’

The head of the Directors Fortnight section showing “Carmen and Lola”, French producer Sylvie Pialat, said the increasing visibility of gay life in Western societies had broadened the palate of filmmaking.

“You see that homosexuality is less and less the main issue in LGBT films,” she said.

“The fact that there are so many LGBT films at Cannes is simply a reflection of real life.”

Groundbreaking gay cinema has long found a home at Cannes. Five years ago, the sexually graphic and emotionally raw feature “Blue is the Warmest Colour” took home the Palme d’Or.

Unusually, the main actresses, Lea Seydoux and Adele Exarchopoulos, who complained of arduous conditions on set, were honoured along with director Abdellatif Kechiche.

Seydoux is serving on this year’s jury for the Palme d’Or led by Cate Blanchett, whose performance in the lesbian period “Carol” reduced Cannes audiences to tears in 2015. MKH

RELATED STORIES: