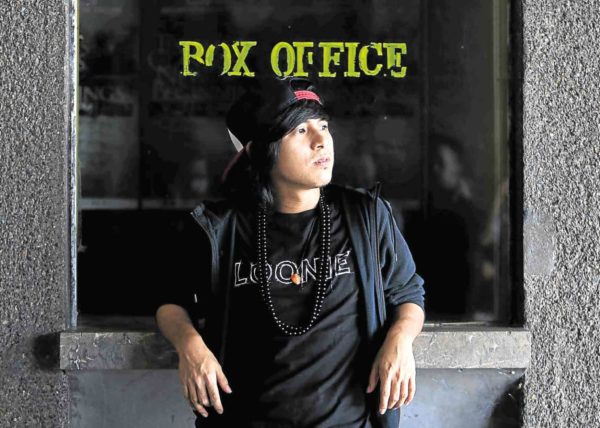

Abra

Can one film turn things around in a society that is on the verge of bedlam? What is the relevance of cinema in a time when young people are dismissed as “collateral damage” in a raging drug war?

With impeccable timing, Albert “Treb” Monteras II’s “Respeto” opened in cinemas on the eve of the 45th anniversary of the declaration of martial law—while the nation was still reeling from the controversies surrounding the deaths of teenagers Kian dela Cruz, Carl Angelo Arnaiz and Reynaldo “Kulot” de Guzman.

The Cinemalaya film, which ran away with seven trophies in the indie fest, centers on Hendrix, a young rapper-drug courier who struggles to rise above his dire situation.

The observation that the movie reflects harsh realities isn’t lost on its director and actors Abra, Loonie and Chai Fonacier.

Treb relates: “The film’s message is very relevant. We feel that people should be made aware of the things that are happening in our country now.”

Says Chai: “Genuine cinema teaches us empathy.” She compares the film’s main protagonists to Kian, Carl and Kulot. “They could’ve been any one of us. They are the Hendrixes … of reality.”

Abra, who plays Hendrix, asserts: “It sheds light on what is wrong with the system. With this film, you see real life … as it is and as it was.”

Loonie agrees: “If you hold a rally, people might just laugh at you. But if you really want to fight for an issue, use a medium like music or film. It’s like mixing the medicine with the food.”

Loonie explains that no one wants to hear complaints all the time. “But if you present the issues in a fierce and creative manner, the audience might understand your intention and not dismiss you as annoying.”

Abra owns up: “Ignorance is bliss … but if you can open people’s eyes to what is happening in our country now, you can help fix what needs to be fixed. You can help expand people’s perspectives.”

Looney exclaims: “There are alternative solutions. Instead of killing addicts, why not make them clean the [polluted] Pasig River?”

Another hurdle is that both the public and the government are not well-versed on the different kinds of illegal drugs, Loonie points out.

“They only focus on marijuana and shabu. How about the designer drugs that proliferate on the party scene? The point is, you cannot solve a problem if you don’t have all the facts.” Loonie considers drug addiction a “health issue.” “Why kill a person who needs to be cured of an illness?”

Abra decries the extrajudicial killings, as well. “No matter how you look at it, murder is wrong. Who gave you the right to kill people?

If we don’t agree, we should just eliminate our enemies? That already happened in

the past [and what good did it do?]…”

Abra believes that our country’s problems go deeper than the drug menace.

Inevitably, things are coming to a head, after decades of malfeasance and corruption, Abra notes. “The problem with our country is that no one follows the law because, for so long, our own leaders have been violating the law.”

Abra rues our nation’s dysfunction. “There’s no sense of being patriotic. We all just want to survive because life is so hard in our country. We should all be given the chance to grow and be successful here. But, our young people are forced to leave the Philippines to fulfill their dreams.”

Chai volunteers: “We’ve lost our sense of kapwa (humanity). We don’t think beyond ourselves …”

In her opinion, art and cinema have the power to heal a divided nation. “Film is a good way to introduce ourselves to each other and tell our stories as a people.”