Los Angeles—Andrew Garfield to be ordained as a Jesuit priest? No less than Pope Francis himself made that quip when he recently met Andrew’s “Silence” director, Martin Scorsese, at the Vatican.

A day before his private audience with the pontiff (a Jesuit himself), Martin screened “Silence,” a fictionalized account of the persecution of Christians in 17th-century Japan, to an estimated 300 Jesuit priests.

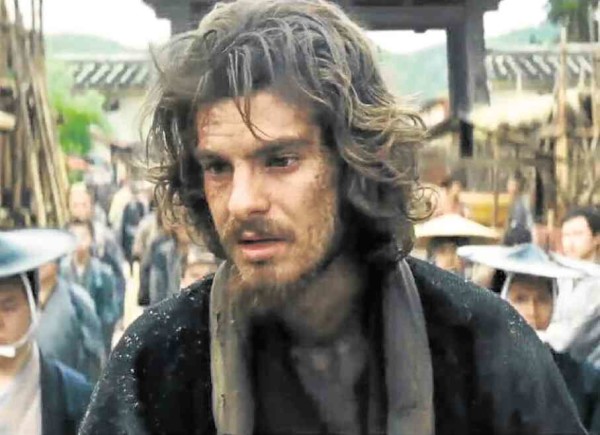

The film, based on the novel of the same name by Shusaku Endo, stars Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver as Sebastiao Rodrigues and Francisco Garrpe, respectively—Portuguese Jesuit priests who face persecution when they go to Japan to find their mentor, Father Cristovao Ferreira (Liam Neeson).

Andrew lamented that he was not able to go to the Vatican with Martin and his group, which included Father James Martin, a Jesuit who served as the film’s consultant and has become Andrew’s “spiritual director” (in the actor’s words).

Andrew is having a banner year. He is superb in this movie, which took Martin over two decades to develop, and in “Hacksaw Ridge,” Mel Gibson’s World War II drama where the actor plays another man of faith, a devout Seventh-day Adventist.

“I wasn’t available to go to Rome with Marty, Father Martin and everybody else because I am working here in Los Angeles right now on another project, which is frustrating,” said Andrew in an early-morning interview at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. “I know that Marty had a pretty profound meeting with the Pope. He was immediately disarmed by how humble and honest the Pope was, and a simple man.

“Marty told me the Pope said something to him which really made me well up,” said the former “Spider-Man” actor who got misty-eyed, too, as he shared this story. “Marty had told the Pope that I had gone through the spiritual exercises in preparation for the role and the Pope was obviously very impressed by that. The Pope said, ‘The next step is to ordain him as a priest.’

“Marty told me that and I am emotional about it now, because there was a part of me that was like yes, maybe (I should be a priest). Maybe now is the time to abandon all this acting nonsense and really do something with my life.”

Andrew, who was born in LA but grew up in England, added, “Of course, the impulse of the missionaries was a beautiful one, that sometimes created more destruction than they could foresee. The interesting thing about the film for me is that these two young men and their mentor in years prior go out with the best intentions. But they realize then in fact that it’s such a complicated thing because what Rodrigues discovers is that in order to truly serve God, he must abandon God. Quote, unquote.

So the feedback has been pretty overwhelming from the Jesuit, Catholic communities, and the agnostic and atheist community, as well. Because this feels like a film for everybody Andrew Garfield

—RUBEN V. NEPALES

“He must publicly exile himself from the doctrine of the Church in order to truly serve God, in a way that is full of love and compassion and service to his fellow man. This is a very tricky conundrum because for the rest of his life, he has to live a life of shame, a life of exile from the Church, knowing only inside that he is still attempting to live for Christ, live for God.

“So the feedback has been pretty overwhelming from the Jesuit, Catholic communities, and the agnostic and atheist community, as well. Because this feels like a film for everybody, in the same way that ‘Hacksaw Ridge’ felt like it transcended any specific religion and it was about love and love for your fellow man. So the themes are interlinked.”

Ribbed that maybe it’s a good time for him to join the priesthood then, Andrew smiled and quipped, “You know what? Life is complicated (laughs) and I am looking to streamline a little bit. Yeah, maybe it would be kind of wonderful.”

On what he learned from playing these spiritual characters in “Silence” and “Hacksaw Ridge,” Andrew answered, “I learned a great deal. It’s very hard to talk about this stuff because it’s so mysterious, just like the word of God is mysterious. I think that is one of the things that makes this film so special—it offers no answers but only greater, bigger, deeper questions. So what I think I have learned is that I know nothing (laughs).”

The 33-year-old credited two figures who helped him get into Rodrigues’ frame of mind.

“I’d say there were two people who were my main directors, really,” he said. “One, of course, was the director of the film, which was Marty. The fact that he’s been wanting to make this film for 28 years means that just spending time with him and talking about the film, talking about the book and the themes, something happens by osmosis where you get ready and you are getting all the information that you need just by being around him and by feeling him and everything that he feels about this man’s journey.

“The second person is Father James Martin, who’s a Jesuit priest in New York City. He became my spiritual director—

and he still is. I had a year to get ready for this, and I shot this just before ‘Hacksaw.’ So that year with Father Martin really prepared me for both films.”

“No amount of time is enough to prepare for convincing myself that I am there (a Jesuit priest in the 1600s coming from Portugal to Macau to Japan) and I’m that person.

“It felt like I needed another five or six years, then get ordained and live as a priest. There was a longing to immerse. But it was nothing but a joy. There was no hard work, and it was easy to fall in love with what it is to attempt to be a man of God.”

Andrew likened his feeling about meeting Martin for the first time to the director’s nervousness about meeting the Pope. “Marty said he was very nervous until the Pope came in the room. Marty felt totally disarmed because the Pope’s energy was very humble, loving and on the same level. I’d say I felt the same way with Marty.

“A soon as I met him, he put me at ease because he knows himself so deeply. There are no airs. He doesn’t judge you. He wants you to be at your most daring and risky and stretching past what you know of yourself.

“The thing that surprised me was how funny Marty is, and how much fun he likes to have on set between takes, unless it’s a scene that requires that sacred silence…on set. He’s always cracking jokes and messing around.”

About his Christian faith, he said: “I fell in love with the Jesuit faith, Father James Martin, the story of Christ and everything that he was, in his essence.”

“He’s a progressive priest. I found that so humble of him, that he is able to sit there, disagreeing with many aspects and staying in the center in order to create the change. That was inspiring to me. I found a lot to love and nourish.”

Andrew marveled at the director’s stamina, especially as they trekked to mountainous locations in Taiwan, which subbed for Japan. “You see Martin Scorsese, who is in his mid-70s now, hiking up these rugged terrains, up the edges of these cliffs with a cane and trudging through two feet of dense wet mud,” Andrew said.

“Marty meditates now, too. He’s a transcendental meditator. So it was about following his lead. He was the band leader, and he was leading us up the mountain every day.

“It was a communal experience. Even Marty was able to let his ego dissolve and allow each scene what he wanted it to be and each actor to do what he was there to do. He guided us.”

By coincidence, Andrew plays yet another man whose inner strength is crucial in “Breathe,” actor Andy Serkis’ directing debut. Andrew plays a man who becomes paralyzed from polio. Did the theater-trained actor choose these difficult roles as a way of testing himself in his own journey?

“That is what I am trying to figure out,” he replied with a laugh. “You just hit very close to something inside me that I am trying to figure out, which is—how do you survive life and all of its extremes, suffering, chaos, anarchy and contradiction?

“How do we live as ourselves, and how do we make the most out of this miracle that we’re all in.

“I am struggling with that question. There’s something about what a priest goes through and what we went through in preparation to a certain degree. That was the experience of making the film. We weren’t eating and sleeping all that much. We were making ourselves as spiritually hungry as possible, so that the spirit would find a way into us.

“That is why we fast and go wandering in the desert. These are old practices that even predate Christianity, of course.”