LOS ANGELES—At 90, Jerry Lewis is still quick and sharp with his legendary comic wit. When the icon was told in this recent press con, “I can’t believe you are sitting in front of us,” he quipped, “Why? Do you want me to stand?”

Delivered with a straight face. We constantly laughed and enjoyed this virtual private show as he reminisced about his career and times in Hollywood. That was the tone of this interview.

Dressed in a yellow argyle vest and shirt, Jerry brought extra California sunshine to a meeting room at the Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills.

In Daniel Noah’s comedy-drama, “Max Rose,” Jerry appears in his first starring role in more than 20 years. He plays a retired jazz musician whose wife dies after six decades of marriage. But a discovery makes him wonder if his marriage—and his life—was not what he thought it was.

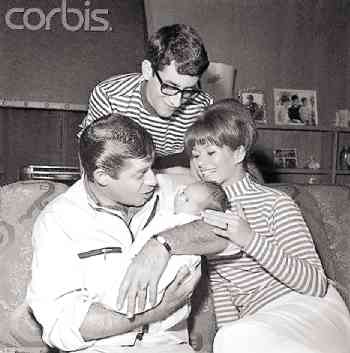

Jerry has a well-known Filipino connection. The actor’s son (with his first wife, Patti Palmer), singer Gary Lewis, was married to a Filipino woman, Jinky Suzara Lewis.

The two met when Gary, who fronted the popular ’60s band, Gary Lewis & The Playboys, performed in Manila. The couple bore Jerry’s first grandchild, Sara Lewis-Spence.

JERRY Lewis’ Filipino connection: The icon holds his first grandchild, Sara Lewis-Spence, the daughter of singer Gary Lewis (who fronted Gary Lewis & The Playboys) and his Filipino wife Jinky Suzara Lewis. Photo courtesy of Sara Lewis-Spence.

Excerpts from Jerry’s press conference:

Who is the most impressive person you have ever met?

John F. Kennedy—he was [a former] President of the United States and my personal friend. We had a friendship up till the time he died.

We had a great relationship because we respected what one another did. He had a great love for film, and we talked about it all the time.

Who were among the figures in Hollywood that you became close to?

I was at David Chasen’s one night and he came over to my table and said, “The man over there is very anxious to meet you. Can I bring him over?” He [then] introduced me to Charlie Chaplin. When I went to shake his hand, I saw my hand trembling. I spent the best two hours of my life with Charlie.

Charlie then invited me to his home. I went there in Lucerne, Switzerland. I spent two weeks at his house. We talked about motion pictures.

The funniest thing in the world was when I saw in his home that he had the same stuff that I had in my home. I had an education, and it was as though I went to Brandeis University. It was an incredible experience, and we became fast friends.

When I left Charlie’s house, he said to me, “I always give a gift to someone who spends time with me in my home. So, can you please tell me what I can get for you that will make you happy?”

I said, “What about a print of ‘Modern Times?’” And it was at my house four days later—with a card on the can that read, “To Jerry, my new friend. Charlie.”

Later, there was a letter from Charlie to thank me for the two weeks. He wrote, “We had a great time. PS, you should learn to give people a present when you meet them.”

I called New York and I had a print made strictly for Charlie of “The Bellboy” and sent it to Switzerland.

From that time on, we talked maybe once a week or twice a month. When he passed away, I felt like something had been taken from me.

What are your fondest memories of working with Dean Martin?

It would take me about seven hours. The most interesting thing about the Martin and Lewis relationship was that audiences all over the world knew that we loved one another.

They knew we were excited about the work we were doing, and there was nothing make-believe with Dean and myself.

Remember, in 1945, the war was over, and this country needed to laugh. We were the next laugh-makers that gave them pleasure.

We were at the Copacabana and we played to more people in 12 weeks than most performers play in a lifetime.

You have had great people who made great work, and we’re all guilty of not giving that work the respect it deserves. I would love to fix that, but I haven’t got a lot of time. So I am saying some of my feelings about the industry as loud as I can make them.

Can you talk some more about teaming up with Dean Martin, especially how it began?

My partner came from a steel town and was brought up with a bunch of very strange people.

When he got to me and I got to him, we built a feeling between one another that made the work simple. I would write a scene for us. I’d talk to Dean about it and that night, I said, “Let’s put it in the show.” He didn’t miss a beat. I am talking about three to four pages of material. He did it like he has done it for 30 years.

He had this incredible photographic memory. He memorized the words. He knew how I wanted to work the scene, what I did versus what he needed to do—and he was brilliant.

If it wasn’t for him, I couldn’t do anything. I was very funny, I knew my job and knew what to do, but without him, I would have never examined what I did.

We had magic. We were getting $250 for the team in March of 1946. And by December of 1946, we were getting $50,000.

It happened fast. When we were together, in three years, we had already earned $4,000,000. So we respected what was happening and we made up our minds not to change anything.

Later on, you and Dean did not talk to each other for 20 years. Why?

I cannot sit here and expound on that because it was so stupid. We both wanted to grow with what we found. We worked hard at learning.

But you get to a point where there’s more that you want to do, and that’s a negative…and turn it into positive, which is what we were able to do. We had such fun together. We had so much respect for each other.

I wanted to take the comedy and give it the life that a director gives to an actor.

Dean wanted to sing more. He wanted to perform and find his audience who loved what he did as an individual, and that was fine. I wanted to know the same thing.

What do you remember about your early times in Hollywood?

Marilyn Monroe naked. You don’t like that answer? I will give you another one. Everything about Hollywood impresses a young performer—transportation, food, rest, sleep, work. I was very happy with Hollywood, and I still am. It’s a nice place to live.

When you feel lonely, how do you get out of it?

I go to a cemetery and thank God.

Do you still watch your movies?

Very often I do for educational purposes—my education. I find that when I am writing, particularly when I’m writing a screenplay, I go back to look at some things that worked and more importantly, looked at some things that didn’t. Then, I sit and I fix what I am doing, so I don’t do that again.

You’ve spent your life making people laugh. What makes you laugh?

When I do a film like this one, I am happy and laughing.

Very apt. You are also sending a message to the industry.

Well, it isn’t going to do any good, but you try. And you try because you’re so into the industry and if it means as much to you as it does to me.

And to get a script that was so perfect as Daniel’s…it was my first time in many years in the business to get something that was perfect, and you would like to go and do it now. That’s how I felt about “Max Rose.”

I love movies so much that when I become part of a movie, I make sure that it is in the mental state I am in, which is happy.

You married and had children very young. Then, later on in your life…

Later on in life, I was just banging anyone I could meet.

To what do you attribute the success of your marriage?

Well, the second marriage is on its 38th year. She (SanDee Pitnick Lewis) is, and has been, from day one, the greatest audience I ever saw in my life.

She loved comedy so much that she forgot I was her husband and just waited for me to do something that would give her pleasure.

When I don’t see her, I feel drained in here (points to his heart). I feel there’s something that isn’t there, and it’s missing.

You’ve had close calls, health-wise. Do you follow a regimen?

I ride in the morning. I get up sometimes at 4:15 or 4:30. I’m at my typewriter or my computer by 7, and I work for three or four hours.

I do that, then I spend time with my family. I have a class in Las Vegas with very eager young people who want to be actors or actresses in the film business.

I do two- or three-hour sessions with them, and that is a great pleasure; it’s a joy.

What are your regrets?

You don’t think about regrets. You regret it and move on. You don’t carry them. The things that are negative—you have to look at them and figure out why they happened and make sure they don’t happen again.

How do you like to be remembered?

I don’t care. I want to hear all the good stuff while I am here. I’m not interested in what people will think after I don’t hear it.

E-mail rvnepales_5585@yahoo.com. Follow him at https://twitter.com/nepalesruben.