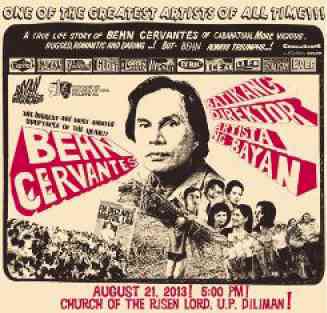

BEFORE he died, Behn Cervantes shared with me that there seemed to be a move to discredit or diminish his seminal contributions to theater in the country, particularly in the significant and influential field of activist theater. Indeed, a conference generally glossed over his productions and their impact.

Since I had worked with him in some of those plays, I felt it was unjust—so, when he died, I sought to set things right.

Fortunately, Behn’s brother, Tony, gave me permission to look through Behn’s papers, notes, scripts, clippings and photos. So, what I knew from actual experience was bolstered in detail by the “evidence” that Behn had left behind.

My first goal in sifting through those voluminous notes was to come up with a list of activist or “engaged” productions Behn had directed and/or written for various groups, including UP Repertory, which he founded in 1974, Kabataang Makabayan’s Sinag-Bayan and SDK’s Gintong Silahis cultural chapters, UP Sigma Delta Sorority and other producers.

Asked by students what activist theater like his productions seeks to espouse and achieve, Behn once shared: “Our role is to reflect the country as it really is: The actual problems of workers, peasants, urban poor, youths, professionals—unemployment, lack of food, corruption, decadence, injustice, cultural imperialism, colonial mentality, censorship, threats to human rights and freedom.”

One of the theater groups that gave him many oppurtunities to vivify and achieve these objectives was UP Repertory. A partial list of the group’s “committed” productions, many directed by Behn, includes (1973) “Short Short Life of Citizen Juan,” “Kahapon, Ngayon at Bukas,” (1974) “Moses, Moses,” (1975) “Pagbibinyag ng Apoy at Dugo,” “Sakada,” (1976) “Iskolar ng Bayan,” “Ang Bundok,” (1977) “Juan Obrero,” “Pagsambang Bayan,” (1978-’79) “Sigaw ng Bayan,” “Panahon ni Cristy,” “Langit Ma’y Magdilim,” (1980) “Titser ng Bayan,” “Hindi Aco Patay,” “Estados Unidos Bersus.”

Other titles: “Barikada,” “Bernardo Carpio,” “Tatlong Dulang Bayan,” “1896: Sa Mata ng Daluyong,” “Istorya ni Bonipasyo,” and “Panginoon ng Dirod.”

Instructively, other “engaged” productions were directed by Behn during the years he spent living in the United States. And, of course, he also megged many other plays and musicals of nonactivist persuasion and essence.

Finally, Behn’s performances as an actor/singer were similarly noteworthy—particularly his portrayals in “The Mikado,” “Waiting for Godot,” “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead,” “Cabaret,” “M. Butterfly” and “Red On Black.”

—So many significant contributions and achievements to recall, review and give due importance to! Our initial focus, however, is on his pioneering work in activist theater, the fruits of which we will periodically share.

It’s still early days in our appreciation, but it’s clear that Behn’s arch-eyebrowed naysayers were wrong in diminishing his seminal contributions to making theater an agent for change rather than escapism in our nation’s life and times.