(Note: This feature story was originally published on February 23, 2015.)

In a definitive biography about singer, actress, producer and industry leader Armida Siguion-Reyna, author Nelson Navarro portrays an icon of feminist ideals.

“Armida: The Singer and the Song” details the life and times of an independent-minded, forthright and unstoppable artist.

“Everybody thought of her as mataray, but she’s more complex than that,” Navarro tells the Inquirer. “She wanted much out of life, on her terms, and got all of that. She had the means, the guts, the stubbornness and determination.”

Armida’s mother, Purita Liwanag, was one of the first graduates of the University of the Philippines College of Music, and was a rising soprano when she became the partner of lawyer-politician Don Alfonso Ponce Enrile. Insisting that a woman’s place is in the home, Don Alfonso made Purita give up her dream of performing, to raise their children in a grand country house in Malabon, away from the gossip of Manila.

Ultimate martyr

Purita, the ultimate martyr, tolerated Don Alfonso’s philandering. (Armida met her half-brother Juan “Johnny” Ponce Enrile when she was 18 and he was 21. Johnny’s mother was Petra Puruganan, whom Don Alfonso met on a campaign sortie. Both strong-willed, Armida and JPE got along and stayed supportive of each other.)

Armida and her sister Irma could not go to prestigious Catholic schools because the enrolment required a birth certificate indicating their legitimacy. So, they studied at the Far Eastern University where their father had connections.

In 1946, Don Alfonso married Purita. Throughout her youth, Armida was fascinated with cinema and the performing arts. To dissuade her, Don Alfonso sent her to the United States for

high school and college education.

While studying at the Georgian Court University in New Jersey, Armida dated an heir who turned out to be a playboy, much like her father. Disappointed, she left in the middle of her course. “I will never [again] be involved with a pretty, rich boy!” she vowed.

Arriving at the Nielsen Tower airport in 1950, she was met by her parents and two young lawyers, one of them, Leonardo Siguion-Reyna. Although he came from a humble background, Leonardo was attracted to Armida’s sophistication and cosmopolitan ways.

Courtship

During their courtship, no one thought the relationship would work. Leonardo was still establishing a name and Armida was already in high society. He loved her more than she loved him.

“Although Armida idolized her father, she didn’t want to marry a man like him and suffer the same fate as her mother,” says Navarro.

The engagement was announced on the eve of Armida’s opera debut as Lucia Lamermoor at the FEU auditorium. Purita’s opera company produced her daughters’ operas.

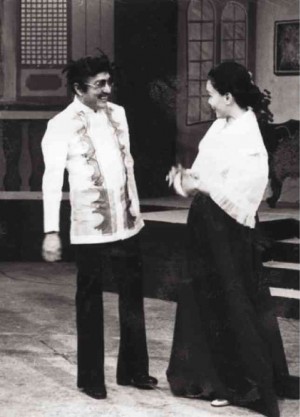

When Armida and Leonardo got married in a society wedding in 1951, Armida set one condition: artistic freedom, especially her opera singing. As a coloratura soprano she also appeared in “Rigoletto” and “La Traviata.” The singing took a sideline when she started to raise her children Leonardo Jr, Monique and Carlos.

PROTESTING censorship (from left): Bienvenido Lumbera, Armida Siguion-Reyna, Behn Cervantes, Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal, among others

As the children grew up, Armida ventured into film, opera and a TV talk show with society doyenne Chito Madrigal.

Navarro cites that Armida’s most significant contribution to the arts is the flourishing of Original Pilipino Music. In 1970, she launched her TV show, “Aawitan Kita,” which showcased Filipino music.

Right mix

“She marshalled the professional support of the industry and gave many singers a break. To be fair, the ratings were high and production values stood out. It brought Filipino music from locales like Ilocos, Bicol and Mindanao,” says Navarro. “Under martial law, ‘Aawitan’ had the right mix. It wasn’t too controversial and everybody appeared in it—Nora Aunor, Celeste Legaspi, the Apo Hiking Society…”

Leonardo, already a top lawyer in labor law, became Armida’s staunch supporter. To finance the productions, big-time clients of the Siguion-Reyna law office became sponsors. With a lifespan of 35 years, “Aawitan Kita” became one of the longest-running shows in Philippine TV history.

Her age started to show in her voice, but Armida persisted. “People ridiculed her but she didn’t mind,” Navarro says.

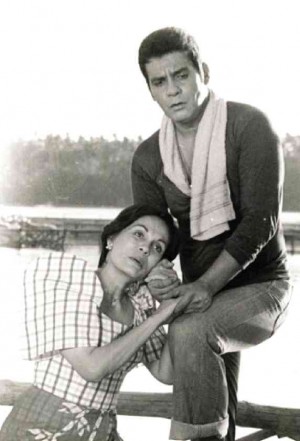

As an actress, Armida’s theater and movie credentials are impressive. She imbued her roles, be they strong women or high-society contravidas, with depth. Many of her films were shot

in her Forbes Park residence in the 1980s,” Navarro points out.

Film production

Armida would do two films a year and spend half of the year in her apartment in New York to soak up the city’s cultural life.

She ventured into film production with the family-run Reyna Films, which aimed to make commercially viable films of high production quality and professional standards. Many of its productions won in international film festivals. In interviews, Armida was proud to say she ran her business with military precision.

Navarro notes that Armida’s last and most prominent role was that of chair of the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board during the term of President Joseph Estrada. She contested uninformed censorship and challenged mediocrity.

Relates Navarro: “In films, she and colleagues like Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal fought a long fight for freedom of expression and against censorship, winning and losing some with conservatives. After Erap’s fall and during GMA’s long nine-year term, she gradually retired and devoted herself to travel and family affairs. She’s a life-long New Yorker and her family still keeps an apartment in the Upper East Side.”

When Leonardo died in 2010, Armida’s enthusiasm waned. “He was her long-time supporter and he had gone beyond the call of duty as a husband,” Navarro explains.

Two years ago, Monique, Armida’s only daughter, approached Navarro to write a book as a tribute to her mother. Navarro made news in 2012 for “Juan Ponce Enrile: A Memoir.”

Of Armida, he says, “She has no secrets. Fear was never in her vocabulary. Love her or hate her, she is herself.”

(The book will be launched Tuesday at Whitespace on Chino Roces Ave. Extension in Makati.)