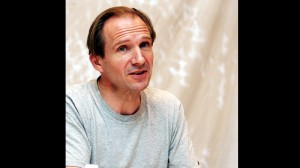

DRESSED casually for this interview, in stark contrast to his Victorian-era character. PHOTO BY RUBEN V. NEPALES

LOS ANGELES—The past year saw a bumper crop of good films, so several others didn’t get the attention that they deserve. One such film is Ralph Fiennes’ second directing work, “The Invisible Woman,” in which he also stars as Charles Dickens. In this follow-up to his directing debut, “Coriolanus,” Ralph fashions a lyrical, absorbing movie based on Claire Tomalin’s investigative biography of Dickens’ secret lover, Nelly Ternan, played excellently by Felicity Jones.

Dickens met Ternan at the height of his career; they became secret lovers until his death. Ralph is also in his element here as an actor, as a man who tries to keep his relationship with Ternan a secret while his marriage to Catherine (Joanna Scanlan) suffers. Ralph delivering a mesmerizing reading of passages from “David Copperfield” is enough reason to see the film. Kristin Scott Thomas costars as Ternan’s mother.

The film is not for everyone; its deliberately unhurried pace and the stillness of the camera may bore some. But for folks who appreciate understated drama, where subtlety and captivating recitations of literary gems are the rewards, “The Invisible Woman” is a must-see.

Below are excerpts of our recent interview with Ralph, who turned up casually dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, a sharp contrast to the Victorian era costumes (Michael O’Connor is nominated for the Best Costume award in the coming Oscars) he wears in the film.

The film makes many moviegoers want to reread, or read for the first time, Charles Dickens’ works. Which of his writings resonated with you?

The work that you can’t ignore if you tell his story is “Great Expectations,” which, by serendipity, I had acted in a version of shortly before I made this film. He wrote it in 1862, around the time when we can suspect that he and Nelly are consummating [their relationship], or he is pursuing her. He has left his wife by then.

It’s guesswork. It could be that Estella, who holds Pip at bay for a long time, was inspired by Dickens pursuing Nelly. We don’t know when they consummated this relationship. Claire Tomalin, who wrote “The Invisible Woman,” is very persuasive that they did have a physical relationship and that there was a child.

From memory, I couldn’t remember any lines. But the speech that Dickens reads to Nelly from the film is from “Great Expectations.” It’s one of the greatest declarations of love in the English language. It was in the film, “Great Expectations” that we did, and I couldn’t resist using it again. It’s just so moving.

What is the most important thing for an actor who is directing for the first time?

To have a really great team. Although the director can end up being given credit, for sure this film, if it’s any good, is the result of a lot of really gifted and talented people—from Rob Hardy, cinematographer, to a brilliant editor (Nicolas Gaster). I learned so much about acting and directing from my editor, Nick.

I have a wonderful costume designer (O’Connor) and a fantastic producer called Gabby Tana. So the most important thing is to have a team of people who will give you criticism and advice and who will guide you. There is a bond of trust. You are a team.

How do you overcome fear when you direct?

SCENE from “The Invisible Woman.” From left: Kristin Scott Thomas, Felicity Jones, Perdita Weeks and Fiennes

Often, the fear is there before you start. When you start driving to the set on the first day of the film to direct, you feel this huge adrenaline [rush] and anxiety. You get on the floor and start making the decisions and you have this team around you, then you feel the rush of creating something together. The fear starts to go. You always have a bit of fear. Blind terror is not good but to have a healthy bit of fear can be good. It challenges you. The sense that you might fail or lose it really or not know what you are doing, that deep insecurity is always there, somehow, some way.

Dickens is a beloved literary figure. How challenging was it to show a side of him that not many people know about?

We are always interested in seeing someone’s underbelly, or other side. I hope that I have [succeeded in showing] Dickens as this sort of vitality—a man who raises a lot of money to help people on the streets and homeless women and children. There is no question— he left his wife in a very sudden and arguably brutal way. But having chosen to tell this story, which is really Nelly’s story, then the bit of Dickens that you are going to be including is the Dickens that falls in love with another woman and leaves his wife.

I feel it’s important that Dickens be seen in his totality, that is, as a man of huge generosity, capable of great acts of love and affection, and very loyal to his friends. It was just that one area of his life where, when all the biographers who adore Dickens get to this point, you find them getting very upset or disturbed that they have to admit that he failed himself, as well as the people around him.

Was Nelly his muse?

I think she was. I have this theory that Dickens had been writing about Nelly. She exists as Anne in “David Copperfield,” a totally idealized woman (you feel Dickens is looking for this angelic, all-loving character). Also, Esther Summerson in “Bleak House.” These women have unlimited kindness, love and affection. He is looking for this person and suddenly he meets Ellen (a.k.a. Nelly) Ternan, this blonde actress. He projects on her—“This is who you are.”

This poor Nelly just doesn’t know what has hit her. She is a serious, slightly guarded young woman who has the force, or Dickens’ imagination, sort of projected on to her. That’s why I think Estella possibly could be a version. Because there’s a Dickens going, “You are the angelic person I have been looking for all of my life.” And there’s Nelly going, “I don’t think I am, maybe I am not.” And that aloofness becomes Estella, who is holding Pip at bay.

You can have all of these theories but that’s mine. Dickens had been looking for this woman and he finally decided he had found her in Nelly, and despite his treatment of his wife, he was devoted to Nelly for the rest of his life. He adored her. He was completely loyal to her. No one knows quite what that relationship was. I think Dickens was absolutely profoundly in love with Ellen Ternan until the day he died.

The stillness of the camera adds to the film’s mesmerizing appeal. Was that a conscious decision?

What I wanted with this film was stiller camera. The composition of the camera is very strong, so that’s maybe what you were sensing. A director I admire a lot is Japanese director (Yasujiro) Ozu. I love the stillness … a distillation and simplicity in his films that I find very exciting and very humane. So that was a factor in these very still frames that we chose.

(Email the columnist at rvnepales_5585@yahoo.com. Follow him at https://twitter.com/nepalesruben.)