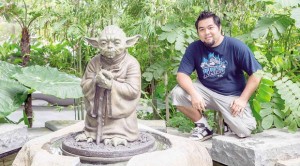

GEM CADIZ with Yoda statue in the garden of Lucasfilms Singapore. His true-life “Yodas,” he says, are his parents Gemelo and Melvyn, and wife Amylene.© 2014 LUCASFILM LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

What is a creature or cloth simulation artist? Can a person be both? And should this matter to a moviegoer?

The Inquirer sat down recently with Gem Ronn Cadiz, a young Filipino animator at Lucasfilm Singapore, who explained the intricacies via a demo video. His presentation was fascinating and enlightening but, midway, our movies-as-escape orientation kicked in, and we wanted to know no more; otherwise, we’ll never again enjoy animated (full or partial) films as much as we do.

Gem, 31, hails from Mandaue City in Cebu but now calls the city-state home, with wife Amylene. Specifically, he works in Lucasfilms’ Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) division, an Oscar-winning visual effects company founded in 1975 by filmmaker George Lucas, creator of “Star Wars.” ILM has worked on about 300 films—including, apart from the “Star Wars” series, such familiar titles as “Indiana Jones,” “Harry Potter,” “Jurassic Park,” “Star Trek,” “ET” and “Avatar.”

In his four years with the division’s Creature Development department, Gem has been part of the teams that worked on several episodes of “Star Wars: The Clone Wars” TV series, the Oscar-winning (full animated feature) “Rango” (2011), portions of the movies “Transformers: Dark of the Moon” and “Pacific Rim” (2013), and Transformers: The Ride, in Singapore’s Universal Studios theme park.

Nuts and bolts

A new team that again includes Gem as a “flesh and rigid simulation” artist and another Filipino animator, Ryan Rubi, is working on “Transformers (4): Age of Extinction,” due for worldwide release in June.

Gem’s official designation is “creature TD (technical director). For the projects previously mentioned, the smiling, fresh-faced 31-year-old performed such other sundry tasks as cloth, flesh and hair simulations.

The technical lingo baffles the uninitiated, but Gem was patient, and eager for us to grasp the nuts and bolts of it. “When a creature that you’re watching onscreen moves,” he began, “it should move realistically, even if it looks like nothing you’ve seen before, and therefore essentially unrealistic.” Oversimplified, that “realism” is what creature TDs like Gem work on.

When he applied online for apprenticeship at ILM, the immediate response was his first exam. Gem received a rudimentary image in his e-mail and was instructed to make it move. The next exam was to “dress up” another image and make the garment move. This is cloth simulation; “rigid” simulation applies to inanimate objects, he said.

Uncharted waters

It was uncharted waters for the IT graduate who thought he was destined to produce architectural and interior design renderings for life. “[The qualifying tests] terrified but stimulated me. I had to learn very quickly.” When at last he was called for a final interview at the Singapore office, he was beside himself. “I never thought I’d ever get out of Cebu,” he said. Neither did his father Gemelo, a retired materials manager on an oil rig, and housewife-mom Melvyn.

By July 2009, he was enrolled in ILM’s Jedi Masters Program (JuMP). Just over a year later, he was on the “Rango” team. The movie was released in February 2011. Gem will never forget the moment it was declared Best Animated Feature Film at the 2012 Oscars. “We were shouting and laughing and…we were just so happy, and weepy.”

Getting on board for “Transformers (3): Dark of the Moon” (released mid-2011) was another weepy moment for Gem. “As a boy I used to play with Transformers (the toy line was launched in the 1980s). The prospect of helping create a ‘Transformers’ movie was overwhelming.”

“Helping,” “collaborating” and “team effort” are as much a part of Gem’s vocabulary as the technical terms used in his JuMP training. “Whatever content we produce is the result of years of ILM experience and very tight teamwork. No one person could ever take the credit,” he said. “If you are selfish or self-centered, this is not the job for you.” (Creature development’s place in the digital production pipeline is just one of 11 “disciplines,” or steps.)

Talent ecosystem

At the recent inauguration of The Sandcrawler, Lucasfilm’s spanking new building in Singapore’s “Mediapolis” district, Kenneth Huff, technical trainer, explained how JuMP serves as the “core piece of a talent ecosystem” that ILM has propagated for nearly 40 years.

Participants are not just trained but “nurtured,” said Huff, 44, a US-born interdisciplinary artist, “helping them continue to be the best visual effects artists in the world.” ILM has invested “heavily” in the artists’ development, he added. “Many of them have gone on to seed the visual effects industry worldwide.” The Singapore base is recreating the ILM culture, he noted.

Tools, techniques

Huff described JuMP Singapore operations: “In six-month, full-time courses, apprentices learn from seasoned artists and begin to master proprietary, state-of-art, Academy Award-winning tools and techniques. They work with assets and shots from recent Hollywood blockbusters. Animators learn using an Optimus Prime rig from ‘Transformers,’ or characters from the Academy Award-winning ‘Rango.’ That access to the best content, experienced instructors and depth of training occurs in only one place in this or any other galaxy—right here, in Singapore, in this studio.”

He continued: “The training coverage is comprehensive…so far, over 50,000 manweeks of apprentice instruction, covering all of the major disciplines in our pipeline.”

The 11 disciplines in the pipeline start with hard-surface modeling (creating new realities…polygon by polygon) and end with rotoscoping (animators trace over footage, frame by frame, perfecting the image, pixel by pixel). In between, there’s organic modeling, texturing, creature simulation, match-moving and layout, character animation, lighting, FX, digital matte/3D generalists and compositing. The movie fan who’d rather be immersed in magic still, need not take all this in.

Immersion

“We have worked with 182 apprentices,” Huff related, “and 125 of them have gone on to become artists in the studio. Once an apprentice is hired as an artist, his training continues. We continue to develop our artists’ skills—for their personal growth, and to allow the studio to take on more, and more complex work. We have lighting artists, who started in the apprentice program, went on to light for the ‘Clone Wars’ TV series and now are lighting some of the most complex and challenging blockbuster shots. This story is retold again and again in every discipline.

“The artists are sent to ILM in San Francisco to keep a constant flow of ideas and information in both directions. So far, 76 have visited the San Francisco studio for over 10,000 hours of immersion. There, we have an incredibly deep bench of industry experts, [including] the brothers John and Thomas Knoll, among the creators of Photoshop. Singapore artists get to know their San Francisco colleagues. When they have a question, they know they can make a phone call.”

As the artists advance in their careers, he said, they become mentors, helping their peers and also helping to educate the next generation of artists. “ILM senior artists, leads and supervisors have taught in Singapore schools, from Nanyang Poly to Nanyang Technical University, from weekend classes to university courses.”

Immense pride

Though these lofty goals are not lost on Gem and his colleagues, they manage to retain, in fact revel in, a childlike disposition that matches the sense of wonder that their efforts stir in viewers of their finished works. (“I still enjoy, very much, going to the cinema and seeing how people react to what we did,” said Gem.)

More than twice during Inquirer’s visit to The Sandcrawler, we were regaled with narrations of more instances of immense pride for ILM Singapore artists, like:

1) Finally watching on the big screen a pivotal scene in “Pacific Rim” (2013) where a Jaeger clobbers a Kaiju: “Months of work, and layers and layers of simulation.”

2) Tom Cruise’s sandstorm chase scene in “Mission: Impossible (4)-Ghost Protocol” (2011): “It wasn’t easy to make that sandstorm go where we wanted.”

It doesn’t seem to matter that most fruits of their labor are seen onscreen for under five minutes, sometimes less.

Gem considers his job as “40-percent creative and 60-percent technical,” but he is hardly ever mindful of the equation. “This is what I was meant to do,” he said, grinning. “Whether I found it, or it found me, I am happy that I’m here.”