Urban legend about Clark Gable spurs stage drama

Clark Gable was in our thoughts while we were watching the New York revival of playwright Clifford Odets’ “The Big Knife,” starring Bobby Cannavale, Richard Kind and Chip Zien, at the American Airlines Theatre last summer. It’s been 64 years since the play was first staged on Broadway by director Lee Strasberg—with John Garfield portraying 1940s Hollywood screen idol, Charlie Castle.

The play’s theatrical etiology is controversial: Castle may be fictional, but his creation was said to have been inspired by an urban legend involving Gable: On his way home from a party celebrating the US victory on Iwo Jima in 1945, the reportedly inebriated actor crashed his car into a tree and allegedly killed a pedestrian.

Louis B. Mayer, the MGM head honcho who’s credited for creating the “star system” during Tinseltown’s golden years, sent Gable into hiding, then “conspired to have a minor executive take the rap, in return for staying on the payroll for life—at a higher salary!” (Gable’s biographer, Lyn Tornabene, later said that the car-crash story was fabricated to draw attention away from Gable’s “secret” stay at a hospital—to get cosmetic surgery on his famously large ears and tobacco-stained teeth!)

Contract

Whether real or imagined, Odets weaves “The Big Knife’s” narrative threads around a similar premise—a case of art imitating life: Castle’s contract is up for renewal, but he’s tired of the crowd-drawing actioners imposed on him by his studio. Moreover, he misses the rejuvenating allure of the legitimate stage, where his acting career began—but, not if studio boss, Marcus Hoff (the outstanding Richard Kind), can help it!

Should Charlie acquiesce to the financial security guaranteed by an artistically “emasculating” 14-year contract? Problem is, Hoff is threatening to dig up the hit-and-run accident that he and his men helped cover up!

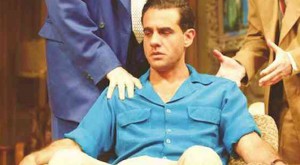

Bobby Cannavale is no slouch at acting. He shared the stage with Al Pacino in “Glengarry Glen Ross” early this year. Whether his point of reference was Garfield or Gable, he knew he had big shoes to fill.

But, while he got both actors’ masculine swagger and smoldering, good looks down pat, he lacked the bearing that “completed” Gable, Cary Grant and Gregory Peck’s dashing pluperfection. Sadly, a stellar presence isn’t something a stage performer can just “act out”—either it’s there, or it isn’t!

Cannavale and his coactors may also have been compromised by Odets’ preference for character development over plot—which, with insufficient preparation, sprung surprises on the audience, to introduce the play’s cautionary twists. As a result, the emotional scenes appeared too broad, blunt and overly dramatic, leaving little room for nuance. As they say, less is more.

The playwright’s “demons” helped Cannavale find Castle’s core. To prepare for the role, the actor told Backstage magazine that he read all of Odets’ plays, as well as his published 1940 journal, “The Time Is Ripe,” which he said should be required reading for actors. He explained, “The guy was merciless on himself! He was a tortured artist who struggled with his contradictory impulses.”